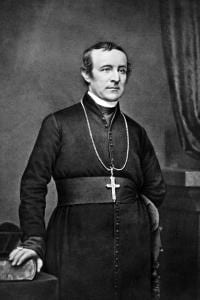

Introduction: The Sacred Heart Review was published out of Massachusetts between 1888 and 1918, covering Catholic news both national and local. Many of its articles sought to defend Catholics against charges of being unpatriotic, so the paper highlighted Catholic contributions to the building up of the American nation. Born in Maryland, John Carroll (1735-1815) became the first Roman Catholic Bishop in the United States. (Baltimore was America’s first Catholic Diocese.) A former Jesuit (the order was suppressed from 1773 to 1814), he also founded Georgetown University, the nation’s first Catholic college. In 1808 he was named an Archbishop. He was the brother of Daniel Carroll, the only Catholic to sign the Constitution, and the cousin of Charles Carroll (of Carrollton), the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Introduction: The Sacred Heart Review was published out of Massachusetts between 1888 and 1918, covering Catholic news both national and local. Many of its articles sought to defend Catholics against charges of being unpatriotic, so the paper highlighted Catholic contributions to the building up of the American nation. Born in Maryland, John Carroll (1735-1815) became the first Roman Catholic Bishop in the United States. (Baltimore was America’s first Catholic Diocese.) A former Jesuit (the order was suppressed from 1773 to 1814), he also founded Georgetown University, the nation’s first Catholic college. In 1808 he was named an Archbishop. He was the brother of Daniel Carroll, the only Catholic to sign the Constitution, and the cousin of Charles Carroll (of Carrollton), the only Catholic to sign the Declaration of Independence.

BISHOP CARROLL IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION, The Sacred Heart Review, Volume 11, No. 1, November 25, 1893, p. 1.

Some years ago Congress took steps to collect material bearing on the history of the United States. From documents, written by John Pope Hodnett, we learn many circumstances. Hodnett says that next to George Washington, John Carroll— who afterwards became our first Bishop — rendered the most valuable services to the colonies. It was Carroll who got the Pope to use his influence to induce the French king to aid America, and it was through Carroll that the Catholic generals — Baron Steuben, De Kalb, Kosciusko and Pulaski— were inspired to link their fortunes with the revolutionists. The story is interesting. Benjamin Franklin was sent by Congress to intercede with the king in behalf of ihe colonies. He was not successful, and had begun to despair. One morning he was sitting in the waiting room of the king’s palace, looking downhearted and forsaken, for he had received a letter from Washington, saying if France did not send over her army, the cause must fail, for his troops were commencing to mutiny, and he could not raise funds to pay them ; they had no rations and their feel were on the ground and cut and bleeding from the cold. Franklin, looking down-cast and woe-begone, was revolving Washington’s last official letter in his philosophical mind, when he was aroused from his melancholy stupor by a voice calling : “Mr. Franklin! Oh, Mr. Franklin!” Franklin jumped up. It was the Pope’s nuncio, who continued: “I have good news for you. I have just got the promise of the king to send over a French army and navy to aid your countrymen.” Franklin, much astonished, clasped the hand of the nuncio. “Oh!” he said, “convey to his Holiness, the Pope, my thanks in the name of the American people. We shall never, no never, forget Rome.” The nuncio said : “Mr. Franklin, you must thank Father Carroll, for it was he who induced the Pope to send me here in the interest of the American people. His letters in favor of your cause were laid by me before the French king and cabinet, and success has crowned his efforts.” Dear reader, if you wish to learn something of the man who, next to Almighty God and Washington, gave you a flag and a country, turn to the Baltimore Cathedral and see his tomb. Washington himself said: “Of all men whose influence was more potent in securing the success of the revolution, Bishop Carroll of Baltimore was the man.” The English king called him “the rebel Bishop, Washington’s Richelieu, who got the Pope of Rome to use his influence at the French court for Americans.” “No, no, sir,” said he, turning to Mr. Pitt, the Prime Minister of England, “I will sign no bill granting Catholic emancipation, after the action taken by the Bishop of Baltimore. He detached America from my dominion by aid of the French army and navy, and the force of Irish Catholics. No, no, Mr. Pitt, you need not stop to argue the question with me; my mind is made up on that point.” “Then,” said Mr. Pitt, “If that is your majesty’s determination, I cannot remain in office, for I am pledged in one of the articles of the union between England and Ireland to grant Catholic Emancipation It is necessary to save the British Empire. I must resign.” ” Then,” said the obstinate king, ” do so, do so!” So Mr. Pitt resigned and Catholic Emancipation was not granted for twenty years afterwards. This shows what Ireland suffered for American independence. It also shows that Bishop Carroll’s influence was mainly instrumental in securing our independence. The people of Boston turned out to receive the French army, led by a Catholic priest, through the streets of Boston. All the ancient burgesses of Boston turned out and went to the Catholic church in complement to the French. And all the old English statutes against the Catholics were repealed on the spot. This is the record of the day. The nine millions of Catholics now in America point to it with pride.— St. Anthony’s Messenger.

(*The above drawing of Archbishop Carroll is by Pat McNamara.)