In 1800’s England, becoming Catholic was, writes historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, “a fate worse than death.” Englishmen, one contemporary observed, feared Catholics “more than they fear heathens.” When England’s Roman Catholic hierarchy was re-established in 1850, three centuries after the Reformation, effigies of bishops were burned in the streets and “No Popery!” was graffiti’d on walls.

In 1800’s England, becoming Catholic was, writes historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, “a fate worse than death.” Englishmen, one contemporary observed, feared Catholics “more than they fear heathens.” When England’s Roman Catholic hierarchy was re-established in 1850, three centuries after the Reformation, effigies of bishops were burned in the streets and “No Popery!” was graffiti’d on walls.

Still, many converted, thanks largely to the Oxford Movement. This started in the 1830’s as an attempt to reclaim Anglicanism’s prophetic role, but led many Romeward, including John Henry Newman, one of its leaders. In 1864, to explain his decision, Newman wrote Apologia Pro Vita Sua (“A Defense of His Life”), perhaps the greatest spiritual autobiography in the English language. As a result, his influence was stronger than ever, especially in Oxford.

On October 21, 1866, Newman received into the Catholic Church a twenty-two year old Oxford undergraduate named Gerard Manley Hopkins, who seemed destined for a great career at Oxford (at least until his conversion). If Newman is remembered as a master of English prose, Hopkins is considered the Victorian era’s greatest poet.

Born into a wealthy, cultured family on July 28, 1844, Hopkins received the best education possible. At Oxford, he befriended future Poet Laureate Robert Bridges, who would publish Hopkins’s poetry. A small, frail man, Hopkins attracted people, writes biographer Robert Martin, by his “openness and spontaneity. He bubbled with uncomplicated humor.”

At Oxford he wrote poems and dabbled in “High Church” Anglicanism, which emphasized ecclesiastical ephemera such as elaborate vestments and decorated altars, candlesticks and incense. Many Oxford men were attracted to these without ever converting. As Anglican clergy, they simply adopted their favorite aspects, such as birettas and cassocks, for example.

Three things really attracted Hopkins to Rome: its doctrine of transubstantiation, its sacramental worldview, and its universality. The “trivialness of life,” he wrote, was “done away with by the Incarnation.” God, he felt, “must have made His Church such as to attract and convince the poor and unlearned as well as the learned.” Other important factors included

Its consolations, its marvelous ideal of holiness, the faith and devotion of its children, its multiplicity, its array of saints and martyrs, its consistency and unity, its glowing prayers, the daring majesty of its claims, etc. etc.

Although Hopkins’s conversion disappointed his parents, they didn’t abandon him. His father felt he was “throwing a pure life and a somewhat unusual intellect away.” While Hopkins might doubt himself at times, he never doubted his decision to convert. It was God, Hopkins insisted, “Who makes the decision and not I.”

After Oxford, Hopkins considered his calling. In May 1868, he simply wrote: “Resolved to be a religious.” That Fall he joined the Jesuits, resolving not to write poetry and concentrate on his religious vocation. Over the next nine years, he studied philosophy, read theology, and taught school. Of his ordination on September 23, 1877, he commented: “I was by God’s mercy deeply touched.”

Hopkins never abandoned his poet’s eye. In August 1874, for example, he wrote: “As we drove home the stars came out thick: I leant back to look at them and my heart opening more than usual praised our Lord to and in whom all that beauty comes home.” A tragic event the following year prompted him to write again.

Reading of a shipwreck that killed five German nuns, Hopkins’s religious superior expressed his wish that someone would write a poem on it. Hopkins soon composed a lengthy poem, “The Wreck of the Deutschland.” A meditation on suffering, the English Jesuits rejected it for their monthly periodical. Hopkins’s sister said: “I wish those nuns had stayed at home.”

In twelve years of priesthood, Hopkins served at several English and Irish schools and parishes. In neither capacity did he truly succeed. As a teacher, he was considered eccentric and somewhat ineffective. His erudite sermons to working-class congregations frequently missed the mark. His superiors wrote: “He is clever, well-trained… but has never succeeded well.”

Hopkins suffered many disappointments. Urban poverty discouraged and depressed him. In Ireland, he was treated as an outsider by his fellow Catholics. He wondered how effective his life as a religious had been; later poems like “Thou art Indeed Just, Lord,” reflected this. Still, he wrote shortly before his death, “I do not waver… I never had since my conversion to the Church.”

On June 8, 1889, Hopkins died of typhoid fever in Dublin at forty-four. Friends and family considered his Jesuit life a failure. Robert Bridges bitterly wrote: “He seems to have been entirely lost and destroyed by those Jesuits.” Yet Hopkins’s last words were: “I am so happy. I am so happy.”

No obituary mentioned poetry. Hopkins had only showed his poems to close friends. In 1918, Bridges had them published. Hopkins was praised for his originality and immediacy, what he himself called the “dearest freshness deep down things,” influencing later poets such as W.H. Auden and Dylan Thomas.

In his greatest poems, Ellsberg writes, Hopkins appropriates “nature to find religious meaning.” This is true in “God’s Grandeur” and “The Windhover.” Robert Martin suggests that Ignatian spirituality allowed Hopkins “to find a sacramental vision” in a way not available elsewhere. In this sense, then, Hopkins’s Jesuit life was a success. For a Jesuit, Father Philip Endean writes, is a “contemplative in action,” who finds “God in all things.” Hopkins leads others to do the same through his poetry.

NOTE: If you’ve never read Hopkins before, I suggest starting with Margaret Ellsberg’s wonderful The Gospel in Gerard Manley Hopkins. It’s an excellent combination of biography, commentary, spiritual reflection, and a nice selection of his greatest poems. I find myself going back to it again and again.

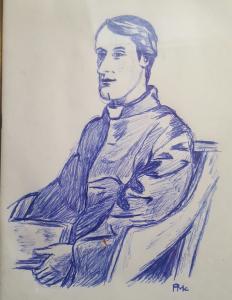

The above drawing of Hopkins is by Pat McNamara.