In the summer of 1854, a young Irish priest named Hugh Gallagher traveled back to his homeland from a far-off city on the other side of the world known as San Francisco. Father Gallagher’s job was to recruit women religious for work in this growing city that needed the kind of help they were best qualified for: teaching children, tending to the poor and sick, nursing the dying.

In the summer of 1854, a young Irish priest named Hugh Gallagher traveled back to his homeland from a far-off city on the other side of the world known as San Francisco. Father Gallagher’s job was to recruit women religious for work in this growing city that needed the kind of help they were best qualified for: teaching children, tending to the poor and sick, nursing the dying.

Soon after he arrived, Father Gallagher approached the Mother Superior of the Sisters of Mercy convent in Kinsale, County Cork. Eight volunteers were taken. A twenty-five-year old Sister, Mary Baptist Russell, was chosen to lead the group on the eight-thousand mile-journey to San Francisco. It would be her first stint as a Mother Superior. Described by one historian as a “fine business woman,” through the course of five decades she would oversee the establishment of “what amounted to a privately sponsored welfare department in San Francisco and Sacramento.”

Born Katherine Russell to an distinguished if not affluent Catholic family in Northern Ireland, she took the name Mary Baptist when she joined the Sisters of Mercy at nineteen. As a young girl, during the height of the Irish Famine, she had volunteered to help poor families. She visited “the sick and poor in their wretched homes, and collect[ed] from door to door the weekly subscriptions of those who were a little better off, and also prepar[ed] her share of the clothing which was distributed to the poor.” In the process, her biographer notes, she discovered “what was to be the work of her life.”

The Sisters of Mercy were a perfect fit for her, a women’s religious community that was active at a time when most were strictly contemplative. They took a special vow of service to “the poor, sick, and ignorant.” Their spirituality flows from founder Catherine McAuley’s (1778-1841) understanding of Christ as mercy itself. For Catherine, mercy was “the principal path pointed out by Jesus Christ to those who are desirous of following Him.” Her charism, writes Mercy Sister Kathleen Healy, “is expressed in prayer and service for the poor.”

The first Six Sisters of Mercy came to America in 1843. Beginning in Pittsburgh, they spread throughout the country. What did they do? They taught school, nursed the sick, ran orphanages and hospitals, residences for women and the aged, vocational training schools and nurseries. By the 1850’s, though, they still hadn’t yet made any inroads on the West Coast. That would be left to the eight Sisters from Kinsale.

The trip from Ireland to San Francisco took three months. Since John Sutter first discovered gold in California in 1848, the village once known as Yerba Buena had grown from three hundred to a city of some 35,000 replete with violence, robbery and mayhem galore. As one historian writes, “San Francisco was then in its raw beginnings.” Russell’s biographer comments: “There was a fine field of labor for Irish Sisters of Mercy.”

They soon established themselves in a small house on Vallejo Street in January 1855 and started nursing the sick and teaching. Anti-Catholicism was a vital presence in California life as the infamous Know-Nothing Party, pledged to eliminate Catholic influence in the United States, elected a governor shortly before the Sisters arrived. The Mayor of San Francisco, Stephen Palfrey Webb, was a Know-Nothing. Protestant doctors in the city hospitals banned the Sisters from visiting patients.

But that Fall, when a cholera epidemic hit the city, the Sisters were out in full force. Their actions did much to alleviate prejudice against them and their Church. One journalist wrote that the Sisters

hurried to offer their services. They did not stop to inquire whether the sufferers were Protestants or Catholics, Americans or foreigners, but with the noblest devotion applied themselves to their relief. One Sister might be seen bathing the limbs of a sufferer, another chafing the extremities, a third applying the remedies, while others with pitying faces were calming the fears of those supposed to be dying. The idea of danger never seems to have occurred to these noble women; they heeded nothing of the kind.

Eventually Mother Russell bought the old city hospital and turned it into St. Mary’s, the first Catholic hospital on the West Coast. Under his leadership, the Sisters were responsible for many “firsts,” including the first homes for unwed mothers in the West and the first subscription library in Sacramento. In the 1870’s, they became the first women to enter San Quentin to visit the prisoners.

They also founded unemployment bureaus, offered adult education, and ran homes for the aged. It was hard work. They wrestled with what one historian calls “smell, noise, inhumanity and poverty” on a daily basis. In 1868 a smallpox epidemic hit the city. The Sisters lived among the victims ministering to them for ten months. But Mother Russell never complained. One Sister said of her: “I would look at her working and scrubbing and feel ashamed of myself and say, ‘She is a fine lady, and look what she does; so how can I complain?'”

One Sister recalled that Mother Russell “had always been remarkable for her skill in nursing and comforting the sick and dying; fear was unknown to her.” Another said: “She provided wedding dresses for brides too poor to purchase them. She visited men in prisons. She stole from the hospital linen supply to give to the poor… One time, she pulled her own mattress down the stairs to give it to a poor man.” Through it all, Mother Russell had what observers described as an aura of peace about her: “When one would go to talk with her, it was almost like going to Confession. You would come away light-hearted.”

By the 1890’s, San Francisco had a strong Catholic presence. And much of the credit for building a Catholic infrastructure therein goes to the Sisters of Mercy under the leadership of Mother Baptist Russell. Her name, it was said, “was a household word all over San Francisco.”

In the summer of 1898, most of the nationwide news coverage focused on the Spanish-American War. But in San Francisco the main news was the passing of a 69-year-old nun, one of the city’s first residents and a backbone of Catholic life in the city now known as “the Paris of the West.” Over fifty priests and thousands of San Franciscans attended the funeral who had brought what Shakespeare called “the quality of mercy” to a booming, lawless town.

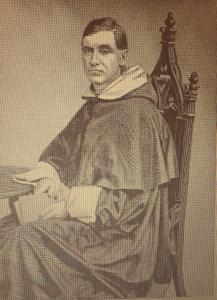

(*The above drawing of Mother Russell is by Pat McNamara.)