When I was growing up in Queens, I had a number of friends whose Irish-born parents had as teens taken “the Pledge,” a vow to abstain from alcohol until age eighteen. Some kept it their whole lives. I found this fascinating, given the fact that alcohol plays such an undeniably large role in Irish/Irish-American culture. Yet outside of the Islamic world, Ireland actually has the highest rate of abstinence from alcohol. One fifth of the adult population refrains completely.

When I was growing up in Queens, I had a number of friends whose Irish-born parents had as teens taken “the Pledge,” a vow to abstain from alcohol until age eighteen. Some kept it their whole lives. I found this fascinating, given the fact that alcohol plays such an undeniably large role in Irish/Irish-American culture. Yet outside of the Islamic world, Ireland actually has the highest rate of abstinence from alcohol. One fifth of the adult population refrains completely.

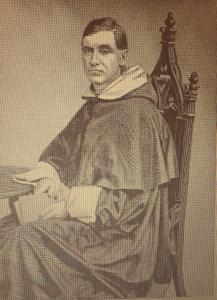

This temperance tradition goes back to the mid-1800’s, when literally millions of Irish men and women publicly took a vow not to drink. At the center of this movement was a Franciscan priest from Cork named Theobald Mathew (1790-1856), a household name in Ireland and America.

Born to a wealthy Tipperary family, Mathew was ordained in 1814. Having grown up in a family that included Protestants and Catholics, he was of a naturally ecumenical bent. Hence it was no surprise that by the 1830’s, when he was ministering in Cork, one of his closest associates was a Quaker minister named William Martin.

In 1835, Martin founded the Cork Total Abstinence Society, but it didn’t really take off until Mathew joined on April 10, 1838. Although Mathew was new to the movement, he had long observed the phenomenon of what he called “habitual drunkenness…. No country in the world was ever affected with that sin so much as Ireland, and to be an Irishman was almost to be branded as a drunkard.” The only legitimate alternative seemed abstinence.

As he signed the society’s register, Father Mathew famously declared: “”Here goes, in the name of God!” Soon he started traveling throughout Ireland, organizing the various temperance societies into a nationwide movement. Following his talks, he had listeners take a pledge they recited:

I promise, with the Divine assistance, as long as I shall continue a member of the Total Abstinence Society, to abstain from all intoxicating liquors, except for medicinal or sacramental purposes, and to prevent, as much as possible, by advice and example, drunkenness in others.

After a blessing, he distributed a membership card and a medal, which depicted lamb below a Cross with the words In Hoc Signo Vinces (“In this sign you shall conquer.”) Scholars estimate that some five million Irish took the pledge at various rallies. Daniel O’Connell, known as “the Great Liberator,” called it “a moral power, a magical intellectual force.”

What happened was remarkable. It was estimated that about half the nation’s population had taken the Pledge. By the early 1840’s, the nation’s alcohol consumption declined by nearly fifty percent. It was said that Father Mathew had “wiped more tears from the faces of women than any other being on the globe except the Lord Jesus.” What was the secret of his success, one biographer asks?

He was certainly not then an accomplished pulpit orator… What then was the charm that held spellbound the close-packed hundreds beneath the pulpit, that riveted the attention of the crowded galleries, and moved the inmost hearts of even those who had come to criticize? The earnestness of the preacher– the earnestness of truth, of sincerity, of belief.

Another important factor was the movement’s ecumenical character. This was not an Irish Catholic crusade, but a movement that happened to be led by a Catholic priest. Mathew encouraged Protestants to attend. This was for all the Irish.

And not just the Irish. Beginning in 1849, Mathew did a lengthy tour of the United States, where he was hosted by newly elected President Zachary Taylor (who toasted him in water). It was estimated that half a million Americans took the pledge. Although Mathew was anti-slavery, he avoided the issue, since many American Catholics (including the Archbishop of New York) were anti-abolitionist. By the time he returned to Ireland, his health had been seriously weakened. He died on December 8, 1856, in Cork.

What Father Mathew accomplished was amazing if not dramatic, but part of the factor in its success was his own force of character, and after his death the movement necessarily declined. Furthermore, other than a pledge not to drink, the movement offered no systematic program of moral regeneration. Alcoholism was seen as a moral failing, not a disease. Still, Father Mathew’s legacy lives on in Ireland, as one who sought to address an issue of serious concern to the lives of many men and women, both in Ireland and abroad.

(*The above drawing of Father Mathew is by Pat McNamara.)