A major reason I got into American Catholic history was to better understand my own background. Most Irish Americans know little about their history. When author Peter Quinn grew up in the Bronx, for example, he recalls: “As far as I knew, Brian Boru was a bar on Kingsbridge Road.” In addition few American Irish, especially those whose ancestors came during the Great Famine, know much about their family history. “Of all the New York Irish families I know who can trace their origins back to the Famine migration,” Quinn notes, “not one possesses a single artifact or memory from that time.”

This is certainly true of my own family, although Ancestry.com has helped me uncover the history of my mother’s family, the Briordys, tracing them back to 1780’s County Cavan. They came to New York in 1845 during the Irish Famine, refugees from a dying country. The first Briordy born in the United States, as far as I can determine from the available records, was Annie Briordy. On August 27, 1846, she was baptized at St. Paul’s Catholic Church on Court Street in Brooklyn.

The Briordys settled in Brooklyn during a time when local newspapers carried “No Irish Need Apply” ads, and anti-Catholic riots racked the streets. They were suspect and subject to anger, resentment and hate. In the 1840’s, one New York City newspaper wrote:

The children of bigoted Catholic Ireland, like the frogs which were sent out as a plague against Pharaoh, have come into our homes, bed-chambers, and ovens and kneading troughs. Unlike the Germans, the Swedes, the Scots, and the English, the Irish when they arrive among us, too idle and vicious to clear and cultivate land, and earn a comfortable home, dump themselves down in our large villages and towns, crowding the meaner sort of tenements and filling them with wretchedness and disease. What are they but mere marketable cattle?

Irish immigrants weren’t even considered human beings.

But the Briordys toughed it out and they stayed in Brooklyn for the next hundred years. Between 1850 and 1940, the U.S. Census shows that the family was at a different location every few years, always in the same neighborhood: Brooklyn’s Red Hook section. (Residents were known as “Hookers;” those living by Gowanus were known as “Creekers.”) Such behavior wasn’t unusual at the time. People moved frequently within the same neighborhood, mainly because of the rent and the need for more space.

I’ve always been interested in my Briordy grandparents, mainly because I was close to my grandmother, and I wanted to know more about them. I wish I’d asked her more questions about her own years growing up in Connecticut and the Bronx. I used to love family gatherings, at which old stories would be recounted. Then, too, I wish I’d paid closer attention.

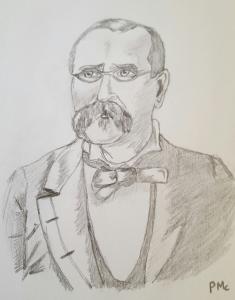

My grandfather Thomas Briordy died eight years before I was born, but I feel like I know him through family lore. He was also a true “B.I.C,” (“Brooklyn Irish Catholic). Born in Red Hook, he was the only one of nine children to make it to adulthood. Family lore has it that he had to leave school at fourteen when one of the Brothers at St. James Academy on Jay Street hit him with a ruler, and he hit the Brother back. So he went to work early on (not so unusual in those days) driving a horse and buggy around downtown Brooklyn.

During World War I, at age twenty, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving with the 106th Infantry in France. His unit was among those that helped break Germany’s Hindenburg Line in 1918. It fascinates me to think that he marched across the Somme, the same ground that saw one of the greatest disasters in military history two years earlier.

Afterwards he worked as a truck driver and married a German American woman from Bedford-Stuyvesant and had a daughter, both of whom died in the postwar influenza epidemic. To the end of his life he never mentioned them. My own mother never found out about it until she was in twenties with two boys of her own.

A few years later, on August 28, 1923, Thomas Briordy married my grandmother, Lillian Murphy, at St. John the Evangelist Church in Park Slope. She liked to note that she was born on the day the Spanish-American War began: February 14, 1898. Lillian was born in New Haven, Connecticut, to Irish immigrants whose first language was Gaelic. Her father, Michael Murphy, was a conductor on the New York-New Haven line. By age twelve, she had lost both parents, and went to the Bronx to live in an apartment on St. Ann’s Avenue and East 140th Street.with her older sister Kitty.

It was understood that she would have to quit school and pay her way, since Kitty had a sizeable family of her own. So she went to work in a sweatshop; no more school. It made her tough, but she never got bitter. In fact, she kept her sense of humor. She also appreciated little things, like the day she had some extra money to buy a pickel, which she ate all the way home. She worked and lived on her own until she met Thomas Briordy (how I don’t know). She was twenty-five when they got married, which was considered pretty old in those days.

After they got married, they lived in Gerritsen Beach, where my mother was born in 1931, and from there they moved to Cypress Hills, at 115 Chestnut Street. They stayed there until the end of World War II, when they finally left Brooklyn for Queens. As my Aunt Grace said, “They don’t call us roamin’ Catholics for nothing.” By then, there were three daughters: Marian (1925-2013), Grace (1927-2008), and Dolores (1931-2012), my mother. (My grandmother liked to note that she had named all three after the Blessed Mother.)

My grandfather, as I mentioned, worked as a teamster, first with horses and then with trucks, literally until the day he died. He had been offered a job as a mounted policeman after World War I, but he turned it down because they didn’t make a lot of money in those days. (Up in Boston in 1919, the whole police force had gone on strike because of this, albeit unsuccessfully.) When I asked my mother what he was like, she said: “He was a nice man.” (That was her highest compliment for anybody.)

My mother remembered him saying the rosary on his knees every night in the kitchen. He was the first one up for Sunday Mass: “C’mon, wake up, it’s time for church!” He would put on his only suit and cufflinks to serve as an usher at Blessed Sacrament Church around the corner on Euclid Avenue.

My grandfather died of a heart attack in 1960, and my grandmother outlived him by 32 years. I wish I knew more about their lives, but I’m grateful for what I do know. I think it helped make me into the person I am today.