Hallucination and psychosis, used as attempts to explain away Resurrection appearances, fails.

Hallucination, aberration in cognition, and psychosis—sometimes skeptics and even hardcore psychiatrists suggest these as possible explanations for what was really going on when New Testament people thought they saw the Risen Jesus. Are such explanations reasonable?

We Catholics, like all our Christian brothers and sisters, are Easter people. The resurrection-life we celebrate marks us. The Risen Jesus isn’t just a nice fable to tell us moral truths—we Christians confess its reality. The Body of Christ has always depended on it (1 Corinthians 15:17). Jesus really is risen; he is risen, indeed!

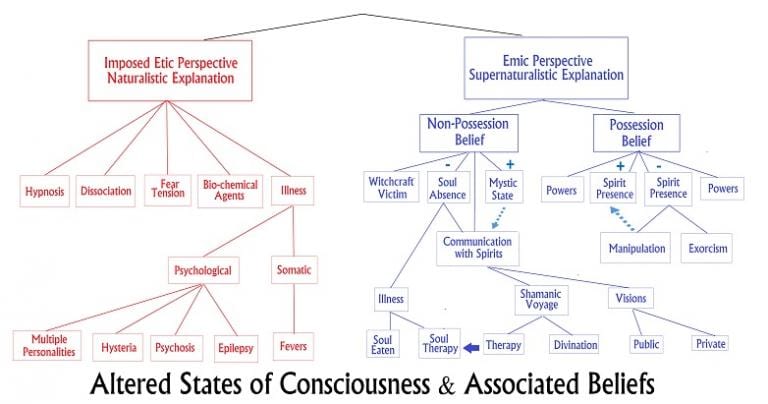

Throughout the Easter Season, we have grappled with the panhuman phenomena of altered states of consciousness experiences. Just recently we applied such insights to Gospel accounts of Jesus walking on the sea. But what would happen if we applied the same to post-resurrection appearance reports found in the Gospels? Watch the video here.

Hallucination Seen Via Etic and Emic

Before we dive further, recall the post on May 1st where we explored the curious expressions “etic” and “emic.” We have to consider New Testament authors as natives, communicators indigenous to a vastly different cultural world of meaning than ours. Native description of human behavior from the indigenous point of view is called by anthropologists an emic description. Seen this way, the 27 New Testament documents make up a treasure chest filled with emic data.

We 21st century Western Bible readers are outside observers to the cultural world of the Gospels. That world, so alien to ours, works very differently. Completely lost, we need a respectful map to navigate these cultural waters. Our comfortable spurious familiarity with Bible stories is no substitute for a respectful reading. When I read anything, I describe what I think is going on. Hopefully this is done from a culturally-respectful model. But whether sound or flawed, my descriptions are called etic, or non-native explanations.

What we Bible readers need is to rightly articulate the emic in an etic way where we, the outside observers, actually understand the authors, or native insiders. In other words, sound Bible study and reading is respectful cross-cultural comparison.

Question—is calling a resurrection appearance hallucination produced by hysterics or grief a successful or failed etic choice? And if failed, what would be a successful etic alternative?

Hallucination = Failed Etic

Many Western skeptics, exegetes, and even theologians, present failed etic conclusions concerning New Testament reports of many things. These include various Western commentaries on the Gospel accounts of ancient Israelites experiencing Jesus alive following his death. Some of their culturally inappropriate descriptions reduce these accounts to mere constructs, literary and “theological,” and certainly not actual events that actually happened.

Others have suggested different failed etic explanations—disciples hallucinated seeing Jesus due to their intense grief. Context scholar John Pilch indicates the weakness of this hallucination position. Says Pilch, “specialists in cross-cultural psychology point out that modern Western psychology is a monocultural science, so integrally bound to Western culture and values as to be nearly useless for application to other cultures.”

Others attempt different, yet equally failed, etic explanations. They claim what happened was a supernatural overriding or violation of physical laws governing the universe. Or, painted theologically pretty, the natural laws simply bowed to their creator permitting an otherwise absurdity. These failed etic responses are very similar to the explanations offered by Stephen and Ricky of Gospel stories where Jesus walked on the Sea.

To reach a successful etic explanation, we first need to honestly inquire about the emic report—what would be the indigenous view of these experiences? Because without that, how can we really understand what the Gospel writers, indigenous folks, are communicating?

Beyond Hallucination and Other Failed Etic

Utilizing the scholarship of Erika Bourguignon, Felicitas Goodman, and John Pilch’s analyses of ethnographic reports is a great start. What if Gospel accounts of experiences of the risen Jesus were reports of altered state of consciousness? Please don’t mistake me to mean by that a fantasy, or a purely psychogenic delusion, or a hallucination in the pejorative sense. No, I do mean a real experience of Jesus really alive.

Unlike hallucination, alternate reality, if understood as part of the total reality not experienced in day-to-day living, but nevertheless just as real, is a respectful and thus successful etic expression of what the emic reports are saying. Visionaries really can communicate with Jesus who is now in alternate reality (with God) via altered states of consciousness.

The indigenous or emic expression of this, found in the New Testament reports, would be that people had visions of the Risen Lord. The respectful etic way we Western people could describe this truth and real event would be that they really encountered Jesus in alternate reality. This happened via trance, an altered state of consciousness, something for which we are all “hardwired.”

Respectful Reading

Scholars like Pilch explain that the indigenous or emic reports in the Gospels tell their audiences that people saw visions. Via the ASC, they encountered a person or persons (angels, Luke 24:4; Jesus, John 21:14-18). In these visions, they were informed that they would “see” Jesus (Matthew 28:7; Mark 16:7). Some visions happened to groups (1 Corinthians 15:6); others to individuals (Acts 9:3-9).

One such individual who experienced the deceased Jesus risen, transformed and alive in a vision, was Mary Magdalene (John 20:11-20). From this experience she goes, commissioned as emissary and apostle to the Eleven, and proclaims—“I have seen the Lord” (John 20:18).

In respectful etic expression, we 21st century Westerners might say that God, through the ASC experience, really disclosed to human beings Jesus’ vindication, cosmic whereabouts, and status to them. They received and interpreted this revelatory experience by way of their culturally-informed brains. But they didn’t invent it like a work of fiction. Neither did pathology cook it up. Thus, even though limited by their cultural and personal constraints always working through culturally-specific interpretations, they nonetheless experienced the reality of Jesus.

Mary’s Hallucination

“Maybe Mary Magdalene was crazy! Maybe she just hallucinated!” But this failed etic proposal is disrespectful because it is foreign to her culture, and therefore unknown. That her ASC vision of Jesus takes place at the tomb makes sense in her world. For such was a common setting for visions of the dead in the Mediterranean cultural world (see “In Search of the Saddiq: Visitational Dreams Among Moroccan Jews in Israel,” by Yoram Bilu and Henry Abramovitch, in “Psychiatry” no. 48, pp. 83-92).

That Mary Magdalene doesn’t initially recognize Jesus aligns perfectly with the expected pattern of a human being in an ASC (see John Pilch’s “The Transfiguration of Jesus: An Experience of Alternate Reality,” pp. 47-64 in “Modelling Early Christianity: Social-Scientific Studies of the New Testament in Its Context”). Consider again this pattern offered by Felicitas Goodman, drawing from her extensive cross-cultural research—

-

People experiencing a vision initially are scared (Mark 16:8; Matthew 28:7-8; Luke 24:4-5).

-

At first, they fail to recognize the figure seen in the vision (Luke 24:15-16, 37; John 21:4).

-

But then the figure offers a calming gesture to the visionary (e.g., “be not afraid”—Mark 16:6; Matthew 28:5, 10; Luke 24:36-37; John 20:28).

-

The figure seen provides self-identification (“It is I…”). Usually this is followed by helpful information or the bestowal of a favor, usually healing or some strategy for solving a problem vexing the visionary (Mark 16:6-7; Matthew 28:6-10, 16-20; Luke 24:6, 38; John 20:21-23).

The Pattern is Not a Hallucination

Now watch how this lines up with the Magdalene in John 20:11-18—grieving (and fearful? John 20:13), she does not initially recognize Jesus, mistaking him for the gardener (20:14-15). The risen Jesus assures and calms Mary and gives self-identification (20:16). Then, new information and a commissioning are provided (20:17).

According to the ethnographic record, 90 percent of cultures on the planet exhibit institutionalized, culturally patterned forms of alternate states of consciousness to solve problems. Ancient Israelites were of the same stock. Problem! Where is Jesus?—the resurrection appearances disclose his whereabouts. Problem! What is he doing now?—the resurrection appearances provide an answer. Problem! Does he still care about us?—the resurrection appearances provide an affirmative.

This ASC Pattern Repeats in “John”

This same pattern happens in the report of Jesus’ disciples later that first night. Therefore the disciples are afraid (John 20:19). When Jesus appears, it’s implied here also that they don’t initially recognize him (he shows them his hands and feet—then, they do, 20:20). The risen Jesus assures them, “Peace be with you” (20:19, 21). Then he commissions and empowers them (20:21-23). Recognize the pattern?

Thus to describe this as either hallucinatory delusion or a séance must be disrespectful, and therefore failed, etic explanations. It is because these anachronistic, ethnocentric explanations belong to our time and culture. They are alien to the cultural world of the Gospels.

Goodman’s pattern can be seen once more in John 21, where the Risen Jesus again descends and appears in vision to some disciples. There we read an emic report that starts with an initial failure to recognize Jesus (John 21:4). Recognition then follows (21:7, 12). Then communication and solving of problems happens through nonverbal communication (sharing a meal of bread and fish, 21:9-14), and verbally (21:15-23).

But What if John 21 is Just A Theological Fiction?

Let’s imagine, for a moment, that this all was a literary creation of a later author. Regardless, this later author still drew from a predictable, Mediterranean cultural pattern. In other words, when ancient Mediterranean people have such an experience—and they did so regularly and routinely!—this is how such people would react. Therefore it’s simply a failed etic to explain the experience of John 21 away as an hallucination produced by insufficient rest plus psychophysiological exhaustion from a night of fishing.