Is your God a bloodthirsty sadistic Jehovah the Hutt?—your view of Jesus on Good Friday tells the tale.

Before reading about Jehovah the Hutt, watch the following video for context—

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEAS7tjKa24

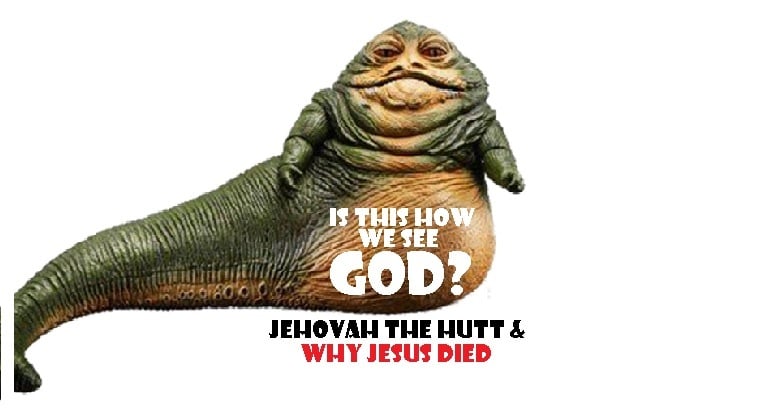

I love Star Wars. There are so many characters and themes to be mined for fun and deep spirituality. Even if you haven’t watched any Star Wars movies or related shows, you might be familiar with Jabba the Hutt. This vile gangster is a disgusting slug who just wants his pound of flesh from hero Han Solo and anyone else who owes him. Jabba is ruthless. If he’s wronged, someone has to pay. Even if the person is innocent, it doesn’t matter.

Many Western Christians make God the Father out to be Jehovah the Hutt. Don’t think so? Allow me to ask you some questions then.

Why did Jesus have to die? Do you think it was because he had to pay a literal price to someone? Is that what you believe literally Good Friday was—a commercial transaction in blood? God is angry. God is pissed off! Therefore, someone must pay. You! Me! We owe God a debt, and the payment is due! Is that how you really think Good Friday was? That way of thinking turns God into Jehovah the Hutt.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KKv7Kf1oHh4

God-talk & Jehovah the Hutt

How did we get to the nasty business of distorting God into Jehovah the Hutt? A couple essential principles help us here. One concerns language, and the other is about our God-talk.

Concerning language, whenever you move it, you change it. That’s inescapable. Whether it is words or sentences, language can only mean what it means where and when you use it. Folks, our language about what exactly went down on Calvary around Passover time, 30 CE, has moved through so many different contexts the past two millennia. Consequently, the inevitable result was that meaning changed through a multitude of re-contextualizations.

Now about the specific language “God-talk,” another way of saying that is theology:

- All theology (God-talk) is analogy.

- And all analogy is rooted in human experience.

- Finally, all human experience is culturally specific.

Ultimately, all theological expression is a culturally limited anthropomorphic analogy.

Before Jehovah the Hutt, Mediterranean Abba

Therefore, armed by these two key principles, let’s talk about Good Friday and where Jehovah the Hutt came from. Jesus is a Middle Eastern male. Specifically, he is a Galilean Israelite peasant turned folk healer. As such, since puberty, Jesus would have been disciplined as the Israelite folk wisdom demanded.

See Proverbs 23:13; 13:24; 10:17; 12:1; 13:1; 15:5; 17:10; 19:18; 19:29; 22:15; 26:3; 29:15, 17; Sirach 7:23; 30:1, 12-13

So, when Jesus prayed “Abba! Father!” the proper or culturally plausible analogy isn’t an American daddy. It is a Mediterranean father. Do American daddies will a shameful and violent death for their sons? Do they beat their postpubescent sons until their backs bleed to create a Mediterranean hero that can hang on a cross for six hours without complaining? Not unless they wish for jail time and psychopaths for children.

What does that do to the Bible? Well, the Bible is the first word we have as Church when talking about God and humankind. It isn’t the only word or the final word, but it is the first word. And inspiration is necessarily messy. Keep that in mind too.

Hey! We are still not at Jehovah the Hutt yet. We’ve got more to learn!

Seeing Resurrection Through Cultural Ideas

The ancient cultural idea of Mediterraneans—Israelites included—was that the Gods ultimately favor the righteous. When in altered states of consciousness experiences, the followers of Jesus experienced him Risen and alive. They knew God had exalted Jesus with great honor and saved him from death. Followers experienced the Risen Jesus as messiah and cosmic Lord, soon to return from sky-vault to inaugurate Theocracy. Clearly, Jesus was honored by God.

Back to the cultural idea that God or “the Gods” favor (honor) the righteous. That happened to Jesus! And the resurrection can be understood in this cultural light. The earliest God-talk about that was the prevailing cultural idea that God does not allow his prophet or holy ones to fall into an abyss. He saves them and glorifies them with honor. Following Easter, the oldest idea followers of Jesus had about the Cross was cultural—it was against God’s plan. Therefore, in raising Jesus, God canceled the Cross. Nice!

Before Jehovah the Hutt, An Honor-Debt

But as time passed and the Parousia refused to happen, a second wave or generation of believers grappled over why the Theocracy hadn’t come yet. People were starting to die in the Jesus groups, and Jesus had not come. So inside new contexts, with language moving around the Mediterranean, new God-talk started percolating.

A new theological idea arose, tied up with the notion that the reason why Israelites were shamefully under foreign rule for so long was that all Israel had dishonored God. Why else would the Patron God of Israel allow his client Israel to be this way?

This was a terribly embarrassing problem. The foreign powers of Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome had successively dominated God’s people for almost 700 years! Indeed, God allowed that to happen, went the reasoning. But at last, by raising Jesus, God showed light at the end of the tunnel to Israel. Finally, God was about to establish Theocracy.

So, when it came to the Cross, God—seen as a dishonored Mediterranean Don who jealously defends his honor—poured out wrath. Jesus the Israelite remained loyal and a truly macho Mediterranean hero in perfect courage. This Israelite male impressed God so much, God waived his right to vengeance. So, since God willed vengeance and wrath to defend his honor, God willed all Israelites to suffer shameful curses. Jesus, the Israelite, took all that, remaining loyal. And God willed that for Jesus for the benefit of others (i.e., Israelites).

Before Jehovah the Hutt, the Synoptic Paradox

The Synoptic Gospels present a weird hybrid of two contradictory ideas. It mixes the theological idea (God willed the Cross to benefit others) and the older cultural idea (God did not will the Cross). Both contradictory statements get poetically woven together by “Mark.” It really is a paradox—God wills the Cross for his honor, benefiting others. God simultaneously cancels it in raising righteous Jesus? Strange!

Curiously, “John” completely rejects any notion that God willed Jesus’ death for the benefit of others. In the Fourth Gospel, the only idea present is the cultural idea. Jesus is crucified in “John” because of the intransigence of the blind Judaeans. God never desired that, and so God rescued and vindicated Jesus. That’s how the God-talk goes in “John.” It’s very different than what Paul and the Synoptics say!

So just to be clear about “John” and the Cross: that God raised Jesus asserted the wrongfulness of his death. Hence, it was overturned by the Highest Judge of all. Contrast that with the theological idea found elsewhere in the New Testament. Namely, the death of Jesus was right and necessary, required by God “save Israel.” What a sharp contrast!

Following “Mark,” the Synoptics juxtapose both interpretations. “Mark” paints both into a smooth narrative sequence. His Jesus predicts he will die and be raised three times (Mark 8:31; 9:30-31; 10:33-34). But “John” utterly rejects this. This Synoptic dissonance between both contradictory interpretations is nowhere to be found in “John.”

Reading “John” Badly and Jehovah the Hutt

Sadly, in our Good Friday celebrations, we Catholics and other Western Christians often read the Synoptic perspective into the Johannine Passion story. Hence we misunderstand the Good Friday Gospel reading (John 18:1—19:42) because the Synoptic view is foreign to “John.” Thus, we distort what “John” means in his Passion Narrative, and also what he means by Jesus being “the lamb of God” (John 1:29; 1:35-36) and the serpent raised by Moses (John 3:14-15).

In any case, we still have not yet arrived at Jehovah the Hutt.

Think about the phrase, “Jesus died for our sins” or “Jesus died for me.” What does that mean? What does it mean to call Jesus (analogy alert!) a “ransom”? What does “atonement” mean? Whatever the case, a transactional analogy was inferred from the New Testament God-talk. See? Not to mention mixing up Synoptic perspectives into the Johannine narrative.

Constantinian Political Religion & Feudal Times

With Constantine, a great deal of imperial cruelty entered the Body of Christ. This contextual change affected the God-talk. Analogies carried the experiences of a new setting. And God began to look like Cruel Omnipotens, the Greco-Roman imperial god of Cruelty, the god of elites in the polis. Relations went from face-to-face and face-to-grace (New Testament times) to face-to-mace (Medieval times).

As Constantine’s political religion grew and reshaped in Germanic feudal times, the Dominicans overemphasized the language of transaction and articulated a violent theology of atonement. The East was spared this problematic theology; Byzantine hymnography stresses the injustice of the Cross. In the West, the Franciscans emphasized different New Testament texts and a different Christological perspective providing a creational and nonviolent theology of atonement. And so, they too were spared.

For Franciscans, as with Eastern Christians, if God wants to see the Icon of what it means to be human, God looks at Christ from all eternity. God isn’t pissed off. God didn’t change God’s mind about humanity, and Christ didn’t change God’s mind, either. According to Franciscan Duns Scotus, Christ came to change humanity’s ideas about God and not God’s idea about humankind.

So was there really a literal commercial transaction required by God? Was there a blood sacrifice that had to be offered up to the Almighty? Not according to the nonviolent theology of the Franciscans. Therefore, no Jehovah the Hutt comes from that tradition.

Enter Jehovah the Hutt

In the West, the Dominican idea, sadly, won out. Later, the Reformers ran with it also. Eventually, this mutated into the abhorrent penal substitutionary theory of atonement. And so God became a cruel tyrant that doesn’t care if an innocent suffers, just as long as someone does and he gets his pound of flesh. Voila!—Jehovah the Hutt.

Why did Jesus have to die? Not because of Jehovah the Hutt. Jesus had to die because, divine, he is the most human being to ever have lived—and humans die. Why did Jesus have to die the way he died? Not because of Jehovah the Hutt. It was because Jesus is the most authentic human that ever lived. This was so precisely because he was God. And that is what we do to authentic humanity when it comes before us—we tear it to shreds, murder it, drown it, crucify it.

Why did God raise Jesus? Because, as the Byzantines say, love does not fall into a void. The Author of Life cannot be contained by the grave.

Now the big missing piece here is St Anselm of Canterbury and his Cur Deus Homo. To get to Jehovah the Hutt, you must pass through Anselm.

More on that, later.