We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

We’re returning to our occasional series of posts on work and vocation (linked at the bottom of this post) in Christian history by Faith and Work Channel senior editor and Christian History magazine senior editor Chris Armstrong. Enjoy!

For the Reformers, as for the early church, the primary meaning of the term “calling” remained the call to Christian discipleship and community. But as Stackhouse says, for Luther and the rest, “to think that vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience were signs of spiritual superiority seemed to them to be moral and spiritual pretense. In fact, living and working one’s ordinary station in life with a heart renewed by the love of Christ, and showing forth there a pattern of life that glorified God and served humankind, enacted a more faithful life of prayerful discipleship.”

The Reformers made this insight into a social reality by closing the monasteries, confiscating their property for the public good, and finding marriage partners for the monks and nuns (famously, Luther’s own wife, Katherine Von Bora, was an ex-nun). And as for the privileged spiritual status of the priesthood, Luther emphasized that every husband, wife, peasant, and magistrate was just as much a priest (in status and ability, if not in function) as the clergy. The ordained ministry was necessary for an ordered society—to have everyone doing the duties of a pastor all the time would be chaotic, just as not everyone was their own lawyer or cobbler—but in a pinch, any laborer could give communion or hear confession.

As he wrote in his Open Letter to the Christian Nobility, “A cobbler, a smith, a farmer, each has the work and the office of his trade, and they are all alike consecrated priests and bishops, and every one by means of his own work or office must benefit and serve every other, that in this way many kinds of work may be done for the bodily and spiritual welfare of the community, even as all the members of the body serve one another.” In fact, when his own sovereign, Frederick the Wise, neglected his administrative duties to do devotional exercises, as if he could serve God better that way, Luther reprimanded him.

Luther’s concern was pastoral. He saw that “People did not want to fulfill mundane God-given tasks such as being a parent, but rather devised their own tasks, such as celibacy, which they thought would please God and make them holy.” As Frederick did, they would neglect the less exciting duties of their earthly callings in pursuit of a higher spiritual call. Thus when Luther talked about vocation, he liked to use the most mundane examples: “the father washing smelly diapers, the maid sweeping the floor, the brewer making good beer.”

It was in such mundane work, Luther believed, not only that we serve others, but that in fact God serves others through us: “[One] should regard all [human labor] as being the work of our Lord God under a mask, as it were, beneath which he himself alone effects and accomplishes what we desire. He commands us to equip ourselves for this reason also, that he might conceal his own work under this disguise . . . Indeed one could very well say that the course of the world and especially the doing of the saints are God’s mask under which he conceals himself and so marvelously exercises dominion.” By doing our appointed work in society, we become means or agents of grace through which God serves others. The farmer who cultivates the fields and brings forth food is in fact carrying out God’s providential care for hungry people. Sin blinds us to this, but that does not make it less true.

Gene Edward Veith puts it like this: “When I go into a restaurant, the waitress who brings me my meal, the cook in the back who prepared it, the delivery men, the wholesalers, the workers in the food-processing factories, the butchers, the farmers, the ranchers, and everyone else in the economic food chain are all being used by God to ‘give me this day my daily bread.’”

Originally published at Grateful to the Dead.

Previous posts in this series:

- Getting the beginning and end of the story right

- We were made to work

- Jesus the incarnate worker God’

- A brass-tacks, real-world theology of work and vocation

- Early Christianity and everyday work

- The contemplative contribution

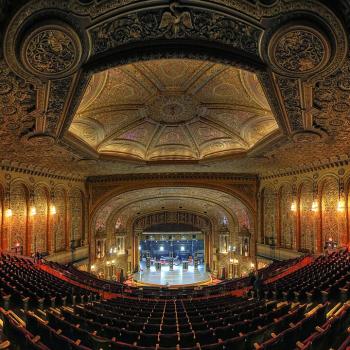

Image: Wikimedia Commons