Third in a series of posts on Luther, Lutherans, and calling by Lutheran pastor Adam Roe with responses over at Cranach by Gene Veith. Read Gene’s response to this post here and see the whole series at the bottom of this post. They’ll appear from time to time in this space for the next couple of weeks. Enjoy!

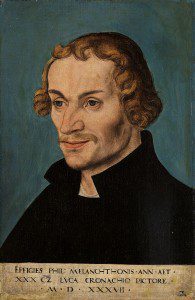

One cannot help but note that the famous Lutheran Augsburg Confession, and its subsequent defense, were written by a layperson. Philip Melanchthon, both loved and held at arm’s length in Lutheran circles, never preached a day in his life, but his role in early Lutheranism was invaluable. For Luther, the problem of the Reformation was not that the Roman Church taught that priests receive a distinctive call within the Body of Christ. Most certainly for Lutherans, the call to the pastorate or priesthood is a distinct function within the church. The Lutheran Confessions state as much when we read, “That we may obtain this faith, the Ministry of Teaching the Gospel and administering the Sacraments was instituted. For through the Word and Sacraments, as through instruments, the Holy Ghost is given, who works faith…”

People within the Body of Christ are graced with differing gifts and talents (1 Corinthians 12). One of the gifts that God gives to people is the ability to lead worship, and he also gives the gift of ordering church life. Lutherans understand that not all people are called to Word and Sacrament ministry, but that does not mean that others within the Body of Christ are of a lesser estate! Indeed, it can be argued that Melanchthon’s theological contributions were greater than that of most of the Lutheran pastors/priests of his time. His role was not more important than that of the parish pastor, but his role was most certainly as important. Luther’s willingness to allow a layperson that sort of authority speaks volumes about the ethos of the Lutheran Reformation. Melanchthon was not trained in a monastery. His early education was received in secular institutions (not unlike Luther), and he became interested in Biblical theology after accepting a Greek teaching position at the University of Wittenberg. There he met Luther, and the rest is history.

Perhaps due to his practical work with laypersons like Melancthon, some of Luther’s finest work resulted from a strong reaction to the view that religious vocations are the only vocations. Luther and some of the other reformers recognized that God’s work within the laity was just as much a vocational ministry as Word and Sacrament ministry. There is no secular realm for the Christian in Luther’s theology of vocation. Gene Edward Veith points out, “When we pray the Lord’s Prayer, observed Luther, we ask God to give us this day our daily bread. And He does give us our daily bread. He does it by means of the farmer who planted and harvested the grain, the baker who made the flour into bread, the person who prepared our meal.” For Luther, God is everywhere.

In this way, the Lutheran view medieval classifications of vocation as failing to see God as abundantly gracious in all of life. God not only blesses us through Word and Sacrament, but also through healers, bakers, bankers, and farmers, just to name a few. One can see how this perspective flips not only the church’s understanding of the priesthood of all believers, but also the view of God’s work in the world around us. The Lutheran vocational view is one in which God is already making Himself abundantly available to us! All we need is to see how God is both blessing us, and using us, in the vocations to which we have been called. In this way, there is spiritual importance in the housewife who feeds her children, because God has ordained the vocation of parent. The question is not whether God ordains us all equally to a ministry, but whether we see God at work in the ministries/vocations to which we have been called.

What is true in everyday life is also true in church-life. Paul reminds us, “And God has appointed in the church first apostles, second prophets, third teachers, then miracles, then gifts of healing, helping, administrating, and various kinds of tongues.” (I Cor 12:28). The Lutheran observation is that in such passages, Word and Sacrament ministry is not  ordained as a higher calling. It is an important calling, but it is just one ministry among others.

ordained as a higher calling. It is an important calling, but it is just one ministry among others.

Adam Roe is the pastor of New Life Lutheran Church in Sterling, IL.