A Therapeutic and Historical Thread

A Therapeutic and Historical Thread

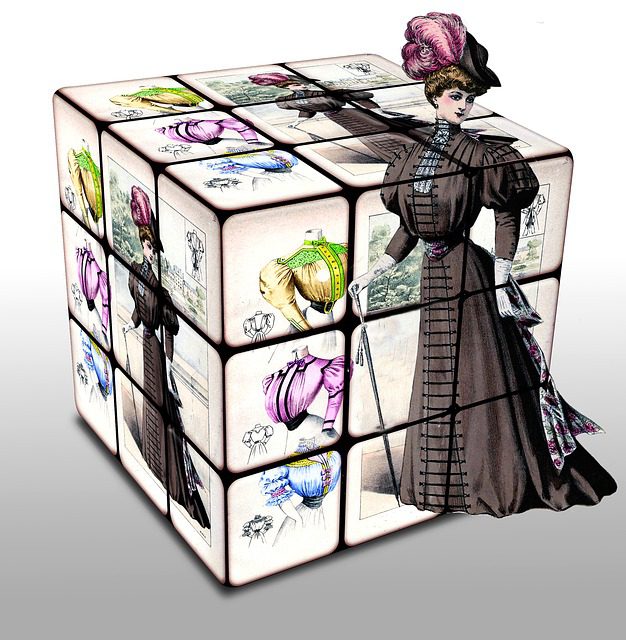

Historically, it is important to remember that dress was (and still is) used to separate classes. Most recently in America dress has been used to distinguish between blue-collar and white-collar workers (terms I presume constructed by white-collar workers who cared more about collars). These distinctions of dress have been woven together in a narrative of “upward” mobility from a rural to a mainly urban and corporate culture. This phenomenon of upward mobility is a modern manifestation of a trend started hundreds of years ago by Greek culture. Greeks prized a life of the mind (leisure) over and above a life of the body (hard, manual work). And this dichotomy has embedded itself in Western culture ever since.

Our tendency to look down upon those who live a life of hard and dirty work is not simply a modern occurrence; yet, the embedded desire in modernity to co-opt higher education as a means of escaping such a life may be. The American Dream finds its way into the mix by promising that every person can have the opportunity to become rich, even extravagant, fueling a sudden neurotic rush towards the top floor of the proverbial office building.

Human nature still tends to emerge: everyone wants to take the elevator rather than the stairs. Thus we have discovered another quick way to the top by donning a certain persona or image via particular articles of clothing. Many companies and ladder-climbers do not want to do the hard work of building customer trust or a credible reputation through consistency and integrity, rather, why wouldn’t we just take the elevator to the top by way of wearing a suit and tie to gain the same thing?

Though our dress may symbolize one cultural ethos or another, it is our actions and our character that are more definitive and formative of who we are. So while we are consistently primed to “dress to impress” to scale the ladders of success via socially manipulative scripts an entirely different paradigm is needed: a call to see past the subtleties of clothing towards the responsibility of words and actions of character.

What actual function does professional attire play in our work? Is there a therapeutic justification to wearing khakis rather than jeans? Put another way, how does professional attire – wearing a collared shirt, dress pants, and dark socks – improve upon the work being done or the quality of the relationships being built? I have yet to discover or understand a reason beyond a careerist expectation, an expectation established to please co-workers and, primarily, bosses or future employers rather than serving customers.

Ours is a deeply aesthetic culture; we are influenced and motivated by the superficial. And if we are not careful, we will begin to treat the suited businessman with more respect and attention than our poor and homeless neighbors. Make no mistake, these issues of clothing are about status and wealth.

Yet they are also moral issues. We presume and/or project that we are financially and morally superior to others based upon our professional attire. Living in such a superficial culture, it is paramount to cultivate the ability to cut through the projections, the hype, manipulation, and gimmicks and to rely upon a person’s (or company’s) word and deed.

Stephen Milliken is the Assistant Dean of Student Life and Resident Director at Montreat College. He recently lived and worked as a resident intern at Lamppost Farm in Columbiana, OH, a non-profit ministry and educational farm seeking to serve the Kingdom by helping to facilitate relationship with God, creation, others, and self.

Stephen Milliken is the Assistant Dean of Student Life and Resident Director at Montreat College. He recently lived and worked as a resident intern at Lamppost Farm in Columbiana, OH, a non-profit ministry and educational farm seeking to serve the Kingdom by helping to facilitate relationship with God, creation, others, and self.