Yesterday I wrote on my Facebook page “The Victorians had the right idea. Put black on and tell everyone to come back in a year.”

Now, I’m a historian of the Victorian era, so I know it was more complicated than that. There were a lot of social rules that may seem overly strict from our perspective, and (as I learned on the rabbit hole of the Internet while looking up Victorian mourning customs) mourning in the full Victorian sense fell out of fashion in part because it was oppressive to the poor, who didn’t have a lot of clothes, and were not very happy with having to dye the ones they had black when someone died. I even found complaints on the rabbit hole of the Internet (from a blog post at Ranker that I will not link to because it tried to eat my computer) that mourning was hard on widows because it required them to “embody grief” for two whole years.

But here’s the thing. You do, and you will, embody grief for two years. And twelve. And twenty-two. I learned from the rabbit hole that the different periods of Victorian mourning were supposed to correspond with the natural rhythm of grief for the place that person had filled in your life – parent, spouse, sibling, or more distant relative. (Widows were to mourn for two years. Parents were supposed to be able to wear mourning for children as long as they wanted.)

Some griefs are complicated. Some deaths open up freedom for people. But in my case, I mourn someone I loved unconditionally, who loved me unconditionally, who was happy in his retirement life of community choir and lunches with his friends and wished to keep it, I know, for quite a while longer before entering on the Beatific Vision.

Wouldn’t it be great if we were able to send some signal that we are embodying grief? Wouldn’t it be great if we could stop everything until we got to the point where we stopped feeling like we suddenly needed to take a nap for random and inscrutable reasons every couple of hours? Wouldn’t it be wonderful if grieving people did not have to answer an email for two whole years?

I have had sweet and loving emails from friends, and I cherish those. My employers were beyond generous in their bereavement policies. But every single innocent business email that begins with “I hope you are well,” no matter that I know it was sent with the best of intentions, enters into my mourning year, screams cheerfully at me, and says “Society is well! We are moving on! We are producing things!” (Barbara Ehrenreich has made a complete fool of herself recently, but before she did that she wrote Brightsided, and it’s still an amazing takedown of our need to be cheerful and say cheerful things at tragic times.)

It’s easy to romanticize the past, and often dangerous. Victorians surely received random letters asking them cheerfully to enter into business ventures from strangers they had never met who didn’t know they were mourning. (Did the fact that they probably got them weekly instead of hourly help? Probably not.) Someone did their laundry. (Seriously, I want to monetize my place in late capitalism by inventing an app that will bring people to the houses of the bereaved to do laundry.) Probably that laundry-doer was in a job that prevented them from grieving because they had to be productive. Getting a chance to be unproductive, ever, is and remains a middle class #firstworldproblem.

And yet, when one of my friends keeps reminding me not to grieve alone, I keep thinking about how you can still grieve alone in a culture full of people because our culture has no vocabulary for saying “stop the world, I want to get off.” Not forever. Not forever. But today.

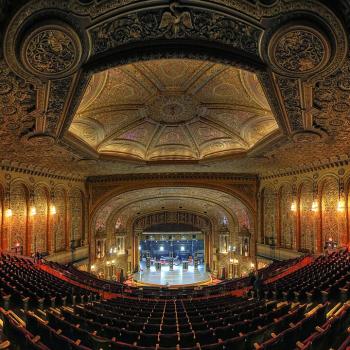

Image: Wikimedia. Video: Archive.org. (No, I don’t know why it’s labeled The Tonight Show either.)