Two years ago, I wrote this post to try to explain (NOT excuse) some things I was seeing and feeling. After writing it, I decided I could not publish it then.

A lot of things have happened since then. My dad died. COVID came. Kristin Kobez DuMez wrote Jesus and John Wayne. (By the way, if you haven’t read this blog post by Kristin, go read it. It’s a hoot.) John Fea wrote Believe Me. I no longer need to explain how otherwise rational people become irrational (Kristin and John have done that.) Nor do I need to plead for understanding. We’re past that.

I decided today to go ahead and post it with a new ending. If nothing else, it won’t stare me in the face from my Drafts folder every time I log on to post something anymore.

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine started a thread on Facebook asking us to name one thing we used to think strongly, firmly, and clearly that we no longer held. It could be as world-sweeping as the existence or non-existence of God, or as minor as whether there’s a correct way to hang the toilet paper. (According to the original patent, by the way, there is.)

Because a large part of my Facebook feed is filled with a certain kind of progressive evangelical who graduated from Christian colleges, there was a certain amount of “I-used-to-be-a-Republican” going on. But I surprised a great many of the thread’s participants with this statement of my previous abandoned commitments: “Rush Limbaugh was right.”

I’ve heard many stories of politically conservative and ex-conservative folks who grew up in theologically rigid households. That is not my story. We said we were evangelicals, but (as I’ve said before) we were not the kind of evangelicals who left things. I have belonged all my life to historically mainline denominations. My relatives read books of mystical theology. A generous Nicene orthodoxy was expected within the family, but asking probing religious questions was not only permitted, it was encouraged.

Not so with politics. I suspect my family had been Republican back to the party’s founding. When I was about eight, I attempted to become the next Ogden Nash and wrote a considerable amount of comic rhyming poetry, most of it political. The only one I remember now – trust me, it was characteristic – is this one:

When Republicans their symbol chose the elephant was chosen.

Why? Because he’s big and strong and ancient, I supposen.

For Democrats, the donkey passes

Why shouldn’t it? They’re all jack&*(^es.

When I got to college, I joined the College Republicans. (There were four of us. It was 1990.) And shortly after I graduated, I remember my mother (who was far more into talk radio of all sorts than I was, though her main interest was in psychology call-in shows) telling me that a new radio host was beginning to broadcast on her favorite station on weekday afternoons. I still remember sitting in a car in a Midwestern parking lot as she dialed in this strange new voice which seemed to be saying things that no one else dared or could. This was before so many other things, like the coming of the Tea Party and Fox News and Dr. Laura. (I was also an early supporter of Fox News. I have much to atone for.)

The question, of course, is why: first, what the appeal was, and secondly, why it ceased to appeal. I can only tell my own story here. There are other people’s stories; I think the perceived “otherness” of non-white bodies plays a larger role in those stories. I will not claim that my family did the right things to actually break down and repent of racial divides, but we saw breaking them down as the right thing to do. My parents deliberately sent me to an integrated magnet school. My grandfather had voted to end official segregation in the Methodist Church.

No, the “other” we were most interested in defining ourselves against was liberal Democrats. And the major reason why we wanted to define ourselves against that other, why that political orthodoxy was so enforced in my childhood, was what I can only call a fear of sophistication. Not, I hasten to add, a fear of money; it was all right to have money to spend on oneself and to give to others; but a fear of those people out there, probably in New York or California, who sympathized with everything that had happened in the 1960s, and knew how to hold a wine glass, and spoke about deconstructing texts, and had sex with people to whom they were not married, and did not believe in God.

This is my childhood’s paradox: we had no fear that asking all the classic theological questions (why do bad things happen to good people? what was the world created for?) could lead to atheism. Our God was large enough for religious doubt. But being the sort of person who would fit in at a New York party? That was religious suicide. (My mother, by the way, was from South Jersey. For purposes of this discussion, that constitutes the Midwest. Trust me.)

This meant many things. But one of the things it meant, as I explained to that Facebook thread of ex-Republicans, was that sex, for us, was a political category. Or at least that was the message I took away from it all, whether or not it was the message intended. Virginity has a long and honorable history as a theological category, but I did not hear about virgin martyrs who shone like flaming swords and refused to let men abuse them for reasons of lust or politics. I heard about virginity as something bad liberals did not practice.

We viewed any argument related to sex as a political weapon that, if liberals successfully deployed it, would make more space in the world for the sorts of people who would fit in at a New York party and reduce the space available for Christians. (The fact that Christians might hold wine glasses at New York parties was not then conceivable to me.) There could never be any systemic injustice that might lead to an unplanned pregnancy. There could never be any good reason for burning draft cards or singing rock music or demonstrating in the streets.

And, though individual commentators might appeal to us (I was a youthful admirer of William Safire and George Will and I claim them as major influences on my adult prose), we viewed the “mainstream media” in general as complicit in this pro-sex, pro-Democrat, pro-New York, anti-Christian, anti-Midwestern message. At root, this is why we distrusted the concept of political correctness. This precise language demanded by those we already feared? It was just another way of being sophisticated. It was just another door to whose lock we would never find the key. And as the voices began to rise which have now in many ways, taken over – Rush, Laura, Fox – we heard them as speaking not that language, but ours.

You can poke logical holes in this all day, starting with the fact that the lives of many of those messengers were insufficiently congruent with the message they were preaching, or at least the message I was hearing from their media sermons. I’ve probably beat you to poking most of the logical holes you will poke. I got off the train before the train arrived at Trump, so I did not make that last logical leap – the one whereby the people I used support are now trusting someone to protect them from liberals who is indubitably from New York (although there is a world of difference on a perceived sophistication-o-meter between Manhattan and Queens) and indubitably has sex. All I can say is that after a long while of “othering” a group and making them a scapegoat, you can forget why you made them a scapegoat. They just are.

How did this become a view I used to hold? It was slow, and painful, and involved conversation after conversation with the sorts of people who know what to do at parties. Some of those conversations even took place in New York (when I lived in North Jersey, which is not the Midwest), though many did not. It involved getting to know actual people who differed from me and learning that they were people, too, not sinister political operatives. It involved getting in touch with the part of me that had loved Woodie Guthrie as a child and made a secret file of protest songs (back when we used to make files of things on paper and put them in actual drawers) and written an entire unpublished novel at the age of 16 set in the late 1960s that wrestled with hippie culture and explored the limits of respectability.

It involved learning that there are more evil things to fear than the possibility we might become sophisticated and lose Jesus in the process. There are other ways to lose Jesus.

In 2012, I was on the way down to my polling place intending to vote for Romney or possibly, timidly, a third party. Along the way I saw a house with a virulently racist display in its front yard picturing a lynching of Obama. I decided that that was a display of death, and in this case voting for life meant voting against it, and I voted for a Democrat for the first time in my life. (I don’t consider myself a Democrat. I will just now occasionally consider voting for one.)

I am, by the way, still profoundly pro-life. I saw my children’s hearts beating on sonograms when each of them was eight weeks old and I’ve never been able to figure out how to draw any line between that day and this which puts that beating heart on the other side of the line. But that’s a theological experience. And I had to leave the idea of sex and sophistication as political weapons behind to get there. I had to learn a theological commitment to making a world that would enable a child fed, not just a child born, as the saying goes. When I had learned to see virginity and marriage as theological statements, then I could see children as theological statements too.

I am not sophisticated. I still wish I could be, but I was not born to it and I still sometimes have flashbacks trying to eat sushi and tofu, much as I love them both. (One participant in the Facebook thread said she had a lot better success getting a conservative relative to eat tofu cheesecake when she called it soybean cheesecake. I totally get this. Soybeans are healthy. Farmers grow them outside our windows. Tofu might make you think of hippies.) From a cultural perspective, it would have made getting a Ph.D. in religion much easier if I could have been sophisticated, if I could have approached people at parties and said, archly, “So what is your latest project?” I will always be a corn-fed Midwesterner who believes in the Nicene Creed and doesn’t have projects.

But-

It was at this point in 2018 that I ended with some justifications that I have now deleted. I don’t think I have justifications now. I just have some marching orders from The Porter’s Gate (see below) that apply in many, many ways at this moment. And I’d better get to work.

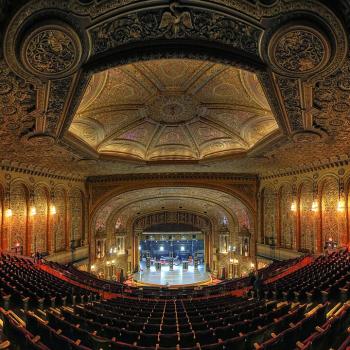

Image: Unsplash.