“Once you come to know the world — truly come to know the world and all its doubt and darkness — can you love it still?” That’s the question the co-founder of the nonprofit Blood:Water addresses in her new memoir. This article is reprinted from Duke Divinity School’s magazine Faith & Leadership, an offering of Leadership Education at Duke Divinity. Read more about Nardella in our recent posts from The Asbury Project.

When Jena Lee Nardella was a 21-year-old college junior, she persuaded members of the Christian band Jars of Clay to start Blood:Water Mission, a nonprofit focused on overcoming the HIV/AIDS and water crises in Africa.

Since the founding of Blood:Water in 2004, Nardella has served as its executive director, and the organization has raised more than $27 million. From the beginning, Nardella hoped to connect concerned Americans — starting with Jars of Clay’s fan base — with African organizations working to bring clean water and HIV/AIDS support to 1 million people in 11 countries.

Since the founding of Blood:Water in 2004, Nardella has served as its executive director, and the organization has raised more than $27 million. From the beginning, Nardella hoped to connect concerned Americans — starting with Jars of Clay’s fan base — with African organizations working to bring clean water and HIV/AIDS support to 1 million people in 11 countries.

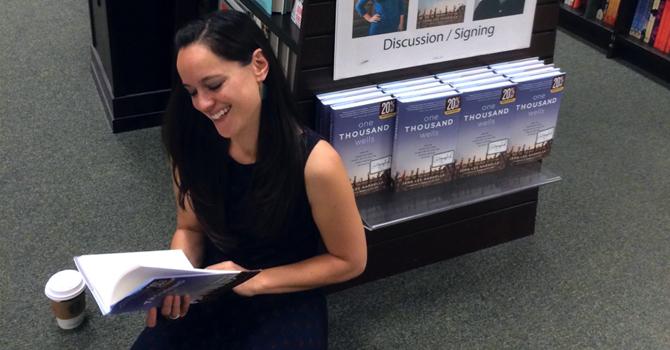

That tidy-sounding story is true, but it masks the stops and starts — and even heartbreak — along the way. In her new memoir, “One Thousand Wells,” Nardella recounts her journey from an idealistic college girl to the experienced Christian leader she is today. The following is an edited transcript.

Q: The subtitle of your book is “How an Audacious Goal Taught Me to Love the World Instead of Save It.” What does it mean to love the world instead of save it?

The surprise for me in writing this story was realizing that it really wasn’t about starting a nonprofit. It was so much more about this question that I’ve had to live out, which is this journey from an idealism — wanting to believe there’s something that each of us can contribute in changing and saving the world — to what happens when you come up against the real challenges of how hard it is to actually do such a thing.

When your idealism crumbles, what do you do with that, and how do you stay with it? Once you come to know the world — truly come to know the world and all its doubt and darkness — can you love it still?

I learned that the more sustainable, more responsible way to step into the world is to choose to love it, which is maybe even a little bit more heroic than trying to save it, a little bit harder to do.

Q: Talk about the idealism that fueled you in the beginning.

We were so motivated by the power of the stories that we had encountered in Africa, and so excited about being able to bring those stories back to the [Jars of Clay] fan base and really ignite response that would allow us to provide HIV and water support to these people that we met.

And it was working. It was so beautiful. It was an unlikely story of a rock band and a 22-year-old being able to actualize these ideas into something tangible.

I think the idealism is so important in the world. I’m looking back at it and realizing that a lot of the things we thought we were going to be able to achieve were not actually possible.

But it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t step into the world or start doing this with idealism. If we ignore the idealism, then we strive for mediocrity. I think that there’s something beautiful about it, even though it’s not necessarily the most sustainable thing to hold on to the whole of your life.

Q: When did you first bump into reality on this journey?

It was when certain relationships that I had in Africa were more deceiving than I had thought — when I came up against my own naiveté and didn’t realize that some of our funds were being misused.

It was also this encounter with senseless deaths. Some of it was losing friends in Africa in the midst of the work. Issues even as basic or simple as clean water are a lot more complex in a place that has this history of extreme poverty and oppression. There’s so much complexity to it I didn’t see when we were dreaming of the Thousand Wells project.

Q: What happened to really cause your idealism to crumble?

As Americans, many of us assume that if something needs to be done, there’s a way to do it. I was pretty convinced that if I just worked hard enough or if we just gathered enough money or mobilized enough communities, certain things would work.

The laws of return on investment don’t apply in many places around the world, and so the idealism started to crumble when my own formula of how to make change happen in the world wasn’t working.

I struggled with understanding how to still believe in a good God when people were continuing to die.

We had the economic crisis in 2008, and all of a sudden the funding that was coming to Blood:Water just shrunk. It all felt like it was crumbling. That was really the key point for me.

I had to decide whether, even if the results that I’m seeking aren’t guaranteed or may never come, is it still worth fighting for? Even if my ideas of what Africa was about or who God is or who I am in the world aren’t what I thought they were when I started, is it still worth sticking with it?

I had a really amazing mentor who basically told me that hope is not passive wishing. It’s an active exercise. For me, the greatest maturing of my own story was choosing to stay with it even when the idealism faded, and to actually make a choice to love the world even as I came to know it differently than what I had originally signed up for.

Q: So you go into it with all this excitement and idealism, and then there’s a point where you write, “We felt like fools trying to put out a forest fire with a dribble of water.”

This community and Blood:Water worked so hard to build rainwater catchment tanks in northern Kenya only to be followed by a completely unexpected season of drought. Then I realized that you can do everything you possibly can but you can’t make the rain come.

And HIV was so much more complex than we thought and came to know. What came out of it was this need to be able to be realistic about what we were facing and what we were capable of doing.

Also, we had to adjust our definitions of success. There’s this concept of “proximate justice,” which is it’s better to have some justice somewhere than no justice anywhere. This is very hard for the idealist, for the 22-year-old idealist.

But there’s only a certain part of justice that I can help move the needle on. And there’s this one place, like Lwala, where all of a sudden we could celebrate small things happening, even if it’s not everything.

Even this year, in 2015, Lwala is a place where there’s a high HIV prevalence rate, but we’ve been able to celebrate the fact that of the 97 babies who have been born to HIV-positive mothers, all 97 have been born negative. So we’ve stopped the transmission of HIV from one generation to another, at least in this one particular place.

I think that’s remarkable. And that’s something that reminds me it’s worth fighting for, even if it’s in one small space in western Kenya. It’s 97 more babies whose stories are different.

Read on for more about how Nardella was betrayed by a friend and how she recovered.