Thursday I was invited to talk about my experiences as a very long-time Zen practitioner at a survey of Buddhism class at the University of Southern California. As I understand these things normally you have to be at least fifty miles from your home in order to be considered an expert on something, and USC is only about twenty-three. However, as one has to cross the entire Los Angeles metroplex to get from Long Beach to the school it becomes roughly equivalent and so I could be there in that authoritative position.

It was fun. And wide ranging, especially when the students were invited to ask questions.

One question turned on politics. I forget the precise wording of the question, but it sparked a reflection on my own ambivalences. The short of it for the class was that I thought in general it was a very good thing. However, there were dangers, as well.

And then this morning as I opened my Facebook account I found a note from someone who is not a “friend” but whom I see on some of the Buddhist pages on occasion. He was lamenting the fact of Buddhist involvement in politics in the West, specifically left-leaning politics, what he called the “disease of social justice.” I admit that ran a red flag for me. And, equally, his dismissal of “political correctness,” which, while I certainly know includes a host of examples of over the top adaptation is in the last analysis, at least as I see it, simply about what used to be called “common decency.” But, now consciously applied to those who have been until now overlooked within our society.

For me it is important to try and not turn away too quickly. And, I have a visceral anxiety about our contemporary convert Buddhist involvement in politics. The fact that nearly all of us who chose to write or speak on the subject fall to the left of the North American political scene is itself a red flag. I am mindful of how the Zen churches in Japan all fell into line in the run up to the Second World War, and how people who are very important in my own spiritual lineages said things that I find reprehensible. The example I most think of are various anti-Semitic statements. Which, also, as most of the writers and speakers had no actual experience of Jews, were in fact using them as a term of art to capture bourgeoisie democracy.

And the writer offered another point that I think cannot be ignored. He offered two quotes. One attributed to the Buddha as among his final words,”With diligence, seek out your own enlightenment.” The other from the lineage source of the Zen schools, the Ancestor Huineng, “A true cultivator of the Way does not see the trespasses of the world.” He, my unsolicited commentator concluded with some snark. Again, making it easy to not attend to the deeper point.

I find it inescapable that he points to something at the heart of Buddhism. Which is that right at the heart of the Buddha’s analysis was a rejection of the world. The original Buddhist sangha was a band first of monks and then of monks and nuns who had turned their hearts from the world and toward their own personal liberation. That seems inescapable. Yes, the community quickly expanded to be a four-fold one of monks and nuns and lay men and lay women. But, the lay person, while throughout Buddhism’s history are thrown an occasional bone, where it is acknowledged almost always reluctantly that even a lay person can achieve liberation, for the most part their task is to support the monastic community and to reap the benefit of that merit in a future life where they will join the renunciants.

Otherwise the world is saha, something to be endured until it can be escaped. And my correspondents point, the real point, was that this world of tears cannot be fixed. And, with that that the whole project of Buddhism is being perverted by our contemporary convert focus on social engagement. The real deal is escape.

Here I find my heart turning back to that gathering of students at USC and their questions. They asked a number about social concerns and what Buddhism in the West might have to say about this. Here I found myself thinking of what has been emerging. A mixed bag, no doubt. Some of it silly. Some of it possibly dangerous. And, a whole lot of it, a great turning toward the suffering of the world as the work of the heart.

Here the obvious differences have to with the emphasis on lay practice, and even when ordained, more from the non-celibate Japanese orders than from Vinaya monastics. At least in the corner of the emerging Western community in which I practice. But, that non-renunciant emphasis which includes women as equal as well as LGBTQ persons, and then, just a quick step to include others historically excluded, particularly around race, has its own deeper currents.

Specifically it includes a collapsing of the idea of karma and rebirth into the present. This is something implicit in much of Mahayana, most obviously in the writings of the Zen masters. Here in the West it has been given full expression. And, we need to be cautious. It is a new emphasis, and its unclear where it will take us.

But, it also means looking for that blessed extinction of the round of literal rebirths has passed like morning dew. And, instead the Buddhist heart calls in new directions. The rest of the teachings do seem to hold sway. Especially the ideas of anicca where we see everything and everyone are temporary, anatta where we see everything and everyone is without any abiding substance, and dukkha were we see that our grasping after that which is passing and without substance is a worm in the heart.

But, the question of letting go of our grasping takes on nuances that while present in early forms of Buddhism are now begin given closer attention. In particular the Mahayana teaching of the twin truths of form and emptiness, and how ultimately our existence as individuals is completely bound up with our existence as part of a great play of circumstances. We are, in this understanding, equally responsible for our own lives and to borrow a term, we are also “our brother’s (and sister’s) keeper. Our salvation, that salvation to be worked out with diligence is now equally the project of our individual lives, and our communal lives.

So…

If this is true, how do we engage the world in a way that is more helpful and less harmful. As it turns out there are any number of hints for us within the Buddhist traditions.

One of my favorite resources for Nikaya Buddhism, the Buddhism that is most closely aligned with the Pali texts, is Walpola Rahula’s What the Buddha Taught. First published in 1959, its simplicity, clarity, and generosity of heart has kept it in print and read to this day. It has also been criticized as an example of the emerging modernist Buddhism of which the “Western” Buddhism I’ve been speaking to is a subset. That caveat included, the Venerable Walpola offers an interesting analysis.

He points out that the Buddha of history while absolutely focused on ethics, spirituality, and philosophy, over the forty years he taught, he also spoke on society, economics, and politics. Among these Venerable Walpola cites the Cakkavattisihanadasutta from the Digha Nikaya (number 26) as an illustration of his concern with the material life. In this text the Buddha specifically addresses poverty (daliddiya) as the cause of theft, falsehood, violence, hatred, and cruelty. Elsewhere in the Kutadantasutta he rejects punishment as the way of solving social ills, saying the fix is to address poverty, and that society through its governments needs to be involved in ways to mitigate the suffering of people.

So, there is ample precedent for social engagement, and even something of a moral compass in the Nikaya literature. More important for me is the implicit call of the two truths. As I have come to understand them the causal world is absolutely true. We arise within this world through causes and conditions. And our choices and our actions create circumstances for others as well as for ourselves. We are all of us caught up, again to draw upon another source, within an indivisible garment of destiny. And, to ground it all, that emptiness of all things that is also true, as fully true as the play of cause and effect, also joins us in a single family of things.

It has been my experience as I’ve come to taste the realities of the consequences of my behaviors and the fact that it is all from before time empty, raises in my heart a sense of care, of compassion for others, of what we in the west call love. And because of this I find a need to redouble my efforts to be of use for others as much as for myself.

This is fundamental to the Buddhism I’ve found.

And, then, beyond that, how to engage? I have seen excesses among my friends, cruelties expressed in the name of generosity. And, I am painfully conscious of the fact that I cannot know enough, that my decisions and actions are always going to be based upon incomplete knowledge. Which, at the same time, does not excuse my engagement.

But, it needs to be a new kind of engagement, something openhanded, something generous. And, the Venerable Walpola also points in a helpful direction. He cited the Jataka Tales, popular legends of the Buddha’s lives before becoming the Buddha. Within them (Jataka I, 260, 399; II, 400; III, 274, 320; V, 119, 378) we find the ten attributes of a king. It is easy to see these as the ten attributes of government. And, I suggest, they can equally stand as pointers for a healthful and genuinely healing engagement with society and its ills.

A very good essay on the subject by Ravi Shankar Singh, enumerates the ten qualities.

- Dāna (charity): Being prepared to sacrifice one’s own pleasure for the well-being of the public, such as giving away one’s belongings or other things to support or assist others, including giving knowledge and serving public interests.

- Sīla (morality): Practicing physical and mental morals, and being a good example of others.

- Pariccaga (altruism): Being generous and avoiding selfishness, practicing altruism.

- Ajjava (honesty): Being honest and sincere towards others, performing one’s duties with loyalty and sincerity to others.

- Maddava (gentleness): Having gentle temperament, avoiding arrogance and never defaming others.

- Tapa (self restraining): Destroying passion and performing duties without indolence.

- Akkodha (non-anger): Being free from hatred and remaining calm in the midst of confusion.

- Avihimsā (non-violence): Exercising non-violence, not being vengeful.

- Khanti (forbearance): Practicing patience, and trembling to serve public interests.

- Avirodhana (uprightness): Respecting opinions of other persons, avoiding prejudice and promoting public peace and order.

I would reframe this as pointers for someone who wishes to engage social justice as:

- We need to start with generosity of heart.

- We need to bind ourselves to standards of conduct that support our aspirations. My friend the Zen teacher James Cordova observes, “the precepts take the form they take because we take the form we take.” That is there is a matching of these precepts and our own lives, which engaged in a lively nd caring matter both contain and liberate.

- We need to recall this is not all about ourselves, myself. It’s never just about ourselves.

- We need to commit to a relentless honesty, especially about our own thoughts and actions.

- We need to try for gentleness, aimed both at ourselves and others.

- We need to recall we are never actually in charge and it would behoove us to act like that was true.

- There are some very important criticisms of the Buddhist call to avoid anger, pointing out how anger can be the only appropriate response to some circumstances – there is nonetheless a legitimate warning about a a clinging anger, what I’d call hatred, which has a napalm effect on the heart. As with all these precepts we need to hold them as all other created things, lightly, knowing there is a time to hold and a time to let go, but that does include a time of holding.

- The Buddha way is one of nonviolence.

- And immediately connected to nonviolence is cultivating a sense of patience, even, even as there is urgency. There are injustices right now. And people are not in a position to wait. And. And, all things come to fruition in their own time. Finding the harmonies, and acting within the realities is critical.

- And the primary principal of this practice has to be not-knowing. Here is the great caution. We do not know how our actions will turn out. There are simply too many moving parts. At the same time we’re not excused. We must act.

It’s going to be one continuous mistake. That’s just how it is. And, I know how true this is of me. I don’t have enough fingers or toes to count my mistakes, blunders, self-serving misstatements and actions. However, if our actions are guided by these ten principles, then I believe we have a somewhat better chance of doing good than ill. So, fall down nine times and stand up ten.

And, I don’t know, maybe that’s as good as it gets.

And, maybe it will even be enough…

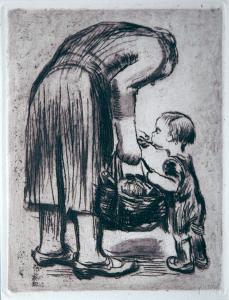

The illustration is by Kathe Kollwitz