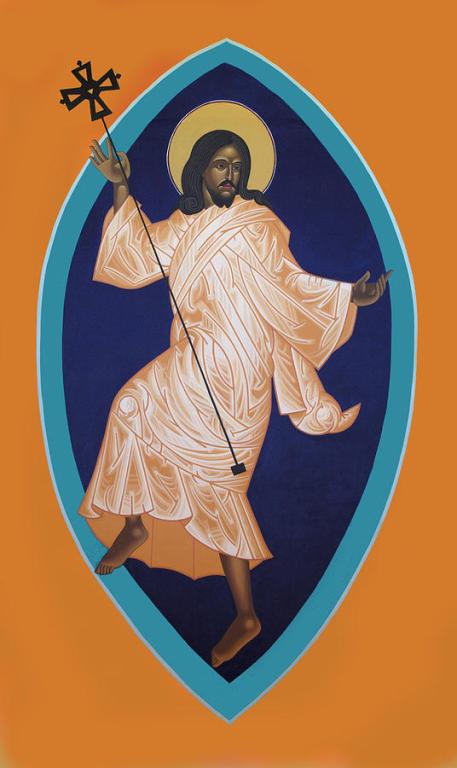

Icon by Mark Dukes

DYING & RISING

A Zen Reflection on Easter

For the last half of my professional ministerial life, I served in some venerable New England parishes. Spiritually we were pretty much generic contemporary Unitarian Universalists. That is, we shared a naturalist and humanist bent. And issues of social justice were very important to us. But at the same time, there was always a bit of a Protestant Congregational Christian sense to the whole thing. This sense was something more in the air than anything else. But it was there. You could find it in the architecture. Some churches had touches in the background such as ancient wall plaques offering the Lord’s Prayer. And it’s there in the way worship services were put together.

Among the consequences of this, shall we say homeopathic Christian sense to our New England churches, was how our Sunday services swelled enormously during Christmas and Easter. People in the larger community wanted some touch of the Christian stories of the normative tradition. But also something that wouldn’t offend secular sensibilities. And we fit the bill. Christmas was easy as pie: the birth of a child as a miracle.

Easter was a horse of another color.

Me, I have a visceral and deeply negative reaction to any emphasis on bunny rabbits and chocolate eggs and vague appeals to spring as the meaning of the season. So, the congregation, by which I mean the real congregation, not the many folk who showed up just for the holidays, but rather the people who gathered in the good and the ill, and made the church alive, would usually look forward to witnessing how I would twist and turn at my wrestle with the Easter story. And with that, something of the Christian church, writ large.

Sadly, too much of Christianity, as contemporary firebrand Protestant pastor John Pavlovitz says, is “a toxic cocktail of power, control, fear, nationalism, and white privilege…” The Easter story can be about the crowd control thing. Believe this is a historical event, and that if you do believe and do what we tell you, you go to heaven. Along with a threat. And if you don’t, there’s eternal conscious torment awaiting.

That’s there. No doubt. Although there is more going on, as well. Always. It’s not, after all, all about crowd control. No real religion is. With that, here, I want to offer an alternative view of the Easter story.

Bottom line, as best I can make it out. The actual of Jesus of history was an apocalyptic prophet who inherited the mantel of his teacher John, after John’s brutal murder. Jesus’ message was that the world was about to end, the rich and powerful would be overthrown, and the poor and endlessly left behind, would be raised up. The kingdom of God, as he called it, as best I can discern from his sayings, was a strange and strangely compelling thing, partially in some other place, and partially here and now.

Jesus’ ministry captured many hearts. For years people shared collections of his sayings and of miracles he was said to have performed. Mainly about healing the sick. Over time communities grew around his teachings and with variations of his personal story.

That “toxic cocktail of power, control, fear, nationalism, and white privilege…” is one version. But, always, always, there was and is more going on. I think of what sustained the American black community through four hundred years of oppression and suffering. I think of the faith of poor people and the oppressed and the stories of God’s love for them. I think of that most mysterious thing the Christian communion and the hints of connection if offers in sharing bread and wine. I think of my own encounters with hurt and healing.

And. And, I think of reality, and how messy and mysterious it really is.

Now, my natural disposition is rationalist. I believe the world described by modern science is more accurate than any other. Although, of course, that view is subject to change as science continues its relentless pursuit of the truths of nature. But this part I’m sure of. We are biological creatures evolved on a tiny planet circling a middling star at the edge of one of a million, million, galaxies in a very strange universe.

So, what is being pointed to in the Resurrection story that calls people even when they know it’s more myth than history? There certainly are a lot of such people. And with that questions come. How can we engage Easter in a healthy and honest manner? Myth, after all, doesn’t have to mean lies. Myths can be our ancestors telling us about who we are and what we might be.

Over the many years I’ve come to a personal faith that expresses the spiritual crossroads of our times. I am at base a Mahayana Buddhist of a modernist sort. Perhaps with some Taoist sensibilities, as well. Now, this isn’t a sermon about Mahayana Buddhism, or Taoism. But it informs my perspectives, so in a nutshell: I believe the world, writ large, is composed of interactions, moments is a good word. These moments mysterious things. And mystery is a right word. These moments arise and, importantly, fall within a play of mutual causality. Practically this means you and I are temporary things, woven out of a mysterious play of causes and conditions. Which are constantly in motion.

For us as humans, we mostly experience this temporariness as some deep anxiety. There are other words that can express these latent and sometimes not so latent feelings. Mostly they’re negative. Off balance, out of kilter. But we also have a latent insight that perceives the whole. Everything is connected, after all. And in encountering that whole as another truth alongside our separation and temporality, brings with it an abiding sense of possibility and even joy.

And this saving insight, wisdom or gnosis are not bad words for it, either; can be found in our ordinary and natural lives. Actually, it can only be found in this life as it is. That sense of one and two, of our unity and our separation as not actually different, manifests in each culture in a multitude of ways. This is the real work of religions, not crowd control.

Like pretty much anyone raised in a religious tradition, my dream life is informed by my childhood religion and the Jesus I started with and who continues to be a part of my life. That influence from my childhood Christianity and the pointers for what is, that I’ve found within that rich tradition are a deep well. Our religions are our dreams. And they tell us about who and what we really are.

For me Zen and Christianity came together as a visceral thing, some thirty years ago during a Zen meditation retreat. Deep in retreat with enforced silence and relentless presence, hallucinations of various sorts are not unexpected. Mostly they’re visual or aural disruptions. Sometimes, however, they take shapes.

In Zen they’re called makyo. Hallucination isn’t a bad translation. When they happen, we’re encouraged to be present, dreams are real too, but not to think they’re offering anything other than our inner lives expressing. In this vision I had, in this makyo, Jesus was walking toward me. Picture whatever Jesus looks like for you. We each get our own, which is kind of cool. His hands, palm to palm together like the Christian prayer mudra, Hindu namaste, or Zen’s gassho. Then he said to me, “I have a great gift for you.”

Within the revery of that moment, not exactly a dream, and not exactly, not a dream; my immediate thought was of my childhood Jesus. The one with all the little children. I felt waves of love washing over me. Then. He spread his hands to reveal those infamous bleeding wounds. A terrible visceral fear leapt into my throat, as he grasped my hands with his bleeding hands.

With that, the pain of worlds birthing and dying ran from his wounds into what are now mine. Then, as fast as it happened, it was over. I was back in the meditation hall, and the simple, relentless rhythms of a Zen retreat.

My hands hurt for weeks. Actually, to this day I can still touch an echo of that hurt if I pay attention. Now blending with the arthritis of old age. Still, on occasion, when I feel a tang of the ongoing hurt in my thumbs, I also touch that makyo, that hallucination, that truth from somewhere deep in my mind, in my heart.

So, what is the Jesus that continues to live within me? And what might it mean for people who self-select to come to a Unitarian Universalist church, of a rationalist, and politically activist bent, on an Easter Sunday?

Easter. When the stories of Jesus sayings and miracles were captured by Greek imagination and wedded to the religious style of their mystery religions. Not as an intellectual enterprise, but as our ancestors whispering truths, if we’re willing to hear them. Truths about living, dying, and rising. Not bunny rabbits and chocolates. Not even spring, although that’s a living current, and it is connected. As is Passover and that other ancient story of pilgrimage, of passing from slavery to freedom.

Easter, I suggest, is taking all that, all of the things of our lives. Rising and falling as they are. And then filled to overflowing with the sorrow and the joy of it, letting it go. And then stepping forward into new worlds.

Easter as a linchpin in our lives. An invitation into a way of life.

To put it another way. My dear friend John Jeffrey, one-time Methodist minister with a long time Buddhist meditation practice, a chaplain and spiritual director, talks about the complexities of our lives. He says, we are “Either-or people, living in a both-and world. We generate suffering for ourselves and each other when we live out that either-or in this both-and world.”

Easter is about correcting our cognitive error, of how we can move from either or, to both and. Along with hints of what that will bring. Can bring.

This is the nub of it all. There’s too much either-or in our thinking. It has roots in logic, “a” in most cases cannot be “b.” But, it turns out our lives are messy things, and not so easily restricted. As we look into our being, as we track our minds, our hearts, we discover that reality is a lot messier. Much richer.

This calls for a shift in perspective. And here I think of the Easter story.

When I consider Easter, I think of us, you and me living in this moment. This bubble of time and space, of energy and longing. We are connected to the past, and we are connected to the future. What happens in this moment shaped by the past, determines much of what will play out going forward.

However. And this is so important. While we are constrained by the events of the past, we have some miraculous ability to adjust in the moment, to shift the course of things. Imagine a small tugboat and great seagoing tanker. It can change who we are going forward as individuals. And we can see it when we engage in the works of justice. One is personal, the other communal. but both are doing the same thing.

So, what does this kind of Easter look like as a lynchpin of our worlds, where the past does not fully determine the future? I think of the story of Jesus and his suffering. I find it our story, all of us. Internally, and communally. We are fractured and separate. We are wounded and isolated. Then, there comes a letting go. Let’s call it death. It can be surrender of our ideas of control, our thoughts determined by the past. Let go. Fall away. Die.

It can be a terrible painful thing. Like death. Like going to the grave.

The poet and teacher Clark Strand tells us “Christianity is a mystery religion. The story it tells is an ecological story, not a theological one—a redemptive story of circular time, rather than a punitive story of linear time, or “end time.” The church doesn’t interpret the Christian story that way because it has spent two thousand years denying its roots in pagan mystery religion. But it’s all there—a secret hidden in plain view…”

And, as the mystery religions told us, as the ancient Hebrew prophets sang, mystery follows upon mystery. A raising from the dead. And with that a new world. New worlds. Our own personal worlds, our communal world. The story of Jesus as our story. The Easter story as our destiny.

So, what does the other side look like? What does an Easter world look like?

The American Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfeld tells of a meeting with his teacher the Thai meditation master, Ajahn Chah. “One day Ajahn Chah held up a beautiful Chinese teacup and said, ‘To me this cup is already broken. Because I know its fate, I can enjoy it fully here and now. And when it’s gone, it’s gone.’ When we understand the truth of uncertainty and relax, we become free.”

We attend to this, and we find an Easter moment, living and dying and living anew.

If, that is, we let go of our certainties. If we allow what was to fall away. And if we open our hearts to what can be. All of that mixed up together. This moment is the linchpin. Here. Now. Accept what was, let it go, and turn toward to the new.

Easter.

The kingdom of God.

The realm of peace and justice.

And what does that look like? You know, when rubber and road meet?

There’s an old term, the “wounded healer.” Here’s a secret. There are no other types of healers. The hope of the world is in your hands. Those hands that hurt. Those hands that exist because of a hundred, thousand, million things. The hands that can in turn, well, bring blessings.

That’s the Easter message I find.

And I offer it as a suggestion for your consideration.

With that, I wish you all a blessed Easter. I wish you a rebirth into new worlds of possibility and hope.

Amen.

Dancing Christ Icon by Mark Dukes