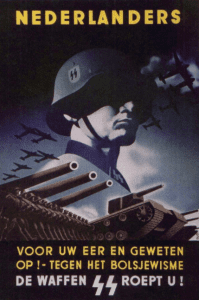

Germany invaded the Netherlands in 1940. The Dutch had declared their neutrality the previous year, but of course the Nazis ignored this, and did not even dignify them with a declaration of war. The fighting was over in less than a week; Queen Wilhelmina escaped to Great Britain, where the Dutch government in exile remained until the end of the war.

I used to think it was ridiculous that the blatant lies of the Nazis worked, and kept working, for so long. But it is difficult to believe that a person will just tell an outright lie to your face. Especially if that person holds a political office, which we habitually assume comes with accountability and consequences. That’s what makes blatant lies effective—especially lies about what you’re going to do, which are hard to disprove.

As before, I’ve edited and shortened this selection, and won’t be charging for this post on Patreon.

We circled up the steps to Tante Jans’s* rooms and Father went to warm up the big table radio. We did not so often spend the evenings up here listening to music now. England, France, and Germany were at war; their stations mostly carried war reports or code messages and many frequencies were jammed. Even Dutch stations carried mostly war news, and that we could hear just as well on the small portable radio we now kept in the dining room. This, though, was to be a major broadcast; somehow we all felt it merited the large old set with its elaborate speaker. We sat now, waiting for 9.30, tense and upright in the high-backed wooden chairs, avoiding as if by a kind of premonition the cushioned and comfortable seats.

Then the Prime Minister’s voice was speaking to us, sonorous and soothing. There would be no war. He had had assurances from high sources on both sides. Holland’s neutrality would be respected. There was nothing to fear. Dutchmen were urged to remain calm and to—

The voice stopped. Betsie and I looked up, astonished. Father had snapped off the set and in his blue eyes was a fire we had never seen before. “It is wrong to give people hope when there is no hope,” he said. “It is wrong to base faith upon wishes. There will be war. The Germans will attack and we will fall.”

He stamped on his cigar stub in the ashtray beside the radio and with it, it seemed, his anger too, for his voice grew gentle again. “Oh, my dears, I am sorry for all Dutchmen now who do not know the power of God. For we will be beaten. But He will not.”

◊ ◊ ◊

I sat bolt upright in my bed. What was that? There! There it was again! A brilliant flash followed a second later by an explosion that shook the bed. I scrambled over the covers to the window and leaned out. The patch of sky above the chimney-tops glowed orange-red.

I felt for my bathrobe and thrust my arms through the sleeves as I whirled down the stairs. Betsie had long since moved into Tante Jans’s little sleeping cubicle. She was sitting up in the bed. I groped toward her in the darkness and we threw our arms around each other. Together we said it aloud: “War.”

For what seemed hours we prayed for our country, for the dead and injured tonight, for the Queen. And then, incredibly, Betsie began to pray for the Germans, up there in the planes, caught in the fist of the giant evil loose in Germany. I looked at my sister kneeling beside me in the light of burning Holland. “Oh Lord,” I whispered, “listen to Betsie, not me, because I cannot pray for those men at all.”

◊ ◊ ◊

One night I tossed for an hour while dogfights raged overhead. At last I heard Betsie stirring in the kitchen and ran down to join her. She was making tea.

The sound of planes died away and the sky was silent. I said goodnight to Betsie at the door of Tante Jans’s rooms and groped my way up the dark stairs to my own. I felt for my bed: there was the pillow. Then in the darkness my hand closed over something hard. Sharp too! I felt blood trickle along a finger.

It was a jagged piece of metal, ten inches long.

“Betsie!” I raced down the stairs with the shrapnel shard in my hand. We went to the dining room and stared at it in the light while Betsie bandaged my hand. “On your pillow,” she kept saying.

“Betsie, if I hadn’t heard you in the kitchen—” But Betsie put a finger on my mouth. “Don’t say it, Corrie! There are no ‘ifs’ in God’s world. And no places that are safer than other places. The center of His will is our only safety.”

*Tante is the Dutch word for aunt; Tante Jans had passed away by 1940, but appears in earlier chapters of the book.