The ten Booms used their house as a refuge for Jews (it is now a museum). They took in the occasional refugee from the beginning of the German occupation of the Netherlands, but became formally connected with the Dutch Resistance in the spring of 1942. In February of 1944, they were betrayed by an informer. Casper ten Boom died at some point during the process; no one knew when or how, save that it was within a couple of weeks of the arrest. Corrie and Betsie were imprisoned, and later taken to Ravensbrück, a concentration camp in Germany itself. Corrie alone survived.

Ravensbrück was less horrific than some of the other camps. Auschwitz was a straightforward extermination camp, for example, while Ravensbrück was not always a death sentence. And the prisoners there were spared the interest of some of the creepiest Nazis—like Ilse Koch, nicknamed “the Bitch of Buchenwald,” the wife of that camp’s commandant. According to some testimony, Koch had lampshades made out of the skin of prisoners with tattoos she liked. Ravensbrück had more ordinary torments. Beatings, starvation rations, cold, parasites, disease, eleven-hour workdays making equipment for the Nazi war effort.

And worship. There were no ministers or priests in the camp, but the ten Booms had smuggled in Bibles which they tore apart book by book, giving them to as many people as they could. The guards might have come in and stopped the whole business—but they weren’t willing to enter the flea-infested prisoners’ barracks, and the services were never discovered.

I’ve edited and abbreviated this passage, and won’t be charging for this post on Patreon.

From the crest of the hill we saw it, like a vast scar on the green German landscape; a city of low grey barracks surrounded by concrete walls on which guard towers rose at intervals. In the very center, a square smokestack emitted a thin grey vapor into the blue sky. “Ravensbrück!” Like a whispered curse the word passed back through the lines. This was the notorious women’s extermination camp whose name we had heard even in Haarlem. That squat concrete building, that smoke disappearing in the bright sunlight—no! I would not look at it! As Betsie and I stumbled down the hill, I felt the Bible thumping between my shoulder blades. God’s good news. Was it to this world that He had spoken it?

Sometimes I would slip the Bible from its little sack with hands that shook, so mysterious had it become to me. It was new; it had just been written. I marveled sometimes that the ink was dry. I had believed the Bible always, but reading it now had nothing to do with belief. It was simply a description of the way things were—of hell and heaven, of how men act and of how God acts. I had read a thousand times the story of Jesus’ arrest—how soldiers had slapped Him, laughed at Him, flogged Him. Now such happenings had faces and voices.

Fridays—the recurrent humiliation of medical inspection. The hospital corridor in which we waited was unheated, and a fall chill had settled into the walls. Still we were forbidden even to wrap ourselves in our own arms, but had to maintain our erect, hands-at-sides position as we filed slowly past a phalanx of grinning guards. How there could have been any pleasure in the sight of these stick-thin legs and hunger-bloated stomachs I could not imagine. Surely there is no more wretched sight than the human body unloved and uncared for. Nor could I see the necessity for complete undressing. But it was one of these mornings while we were waiting, shivering, in the corridor, that yet another page in the Bible leapt into life for me.

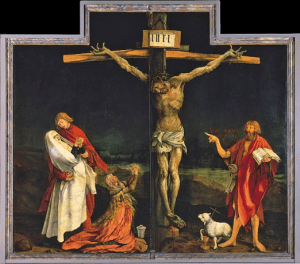

He hung naked on the cross.

I had not known—I had not thought … The paintings, the carved crucifixes showed at least a scrap of cloth. But this, I suddenly knew, was the respect and reverence of the artist. But oh—at the time itself, on that other Friday morning—there had been no reverence. No more than I saw in the faces around us now.

◊ ◊ ◊

They were services like no others, these times in Barracks 28. A single meeting might include a recital of the Magnificat in Latin by a group of Roman Catholics, a whispered hymn by some Lutherans, and a sotto-voce chant by Eastern Orthodox women. At last either Betsie or I would open the Bible. Because only the Hollanders could understand the Dutch text, we would translate aloud in German. And then we would hear the life-giving words passed back along the aisles in French, Polish, Russian, Czech, back into Dutch. They were little previews of heaven, those meetings beneath the light-bulb.