By day she woos me, soft, exceeding fair:

But all night as the moon so changeth she;

Loathsome and foul with hideous leprosy

And subtle serpents gliding in her hair.—Christina Rossetti, “The World” ll. 1-4

Politicus

Like many people, I’ve spent a gigantic slice of the last six years thinking about politics. Like many Catholics, a lot of that slice has been tangled up with my faith. (Can a slice be tangled? Never mind.) This is a notorious habit of Christians in this country—particularly, at least for the last thirty years, when it comes to the issues of abortion and gay marriage.

In a democracy,1 participating in the political system, especially voting, is a normal part of responsible citizenship. The Catholic Church presumes that, at least in countries that don’t bar Catholics from doing so, faithful Catholics will participate as citizens in the normal way. This goes slightly further than the commands expressed in the New Testament, which focused more on paying taxes and leading a quiet life; but of course the Roman Empire was almost as far from a democracy as it is possible to be, and the nature of good citizenship meant something different accordingly. Moreover, insofar as full citizenship and eligibility for public office involved burning incense to the emperor, a religious act forbidden to Christians, there was for centuries no question of full participation in the political process. We were “pilgrims and aliens” in a more immediate, tangible sense back then.

But for the last seventeen hundred years, there have been Christian polities—both culturally and legally. Armenia led the way in the year 301, followed by Ethiopia, and eventually the Roman Empire itself. To this day, a little over a dozen countries (depending on how you count) are officially Christian; and while the US of course enshrines religious freedom and disestablishment2 in the First Amendment, it is, historically, a majority-Christian country.

Mayflower Power

This goes back to some of the earliest English-speaking colonists in North America. The Pilgrims of 1620 weren’t looking for a place where they could be Dissenters in peace; they’d already found that in the Netherlands. They were looking for a place where their faith could be in charge. The theocratic strain has always been a strong one in Calvinism—a minor paradox for a theology that insists so strongly on the sovereignty of God; one wouldn’t think He needed the help.

The idea that America is some kind of promised land or “city on a hill” is a persistent one in our national mythos. It probably comes at least partly from the Pilgrims, who, despite being limited to New England, had and have an outsize influence on the American self-concept. Doubtless some of it also comes from the waves of immigrants, many of them Catholic, who fled the poverty, warfare, and classism of nineteenth-century Europe for the wealthy, spacious, and professedly egalitarian New World.

But the United States inherited Great Britain’s suspicion of Rome. Most of the Founding Fathers were either Deists or Anglicans, and American Catholics have often evinced an uneasy need to prove ourselves against accusations of disloyalty (which are, on occasion, hilarious). Before 1973, that typically meant voting Democratic—they were the progressive and “popular” party, in the sense of being the one that put the needs of the disadvantaged before the interests of the prosperous. After all, a majority of Catholics were poor and often socially despised for ethnic reasons, and pluralism serves the needs of religious minorities.

In a way, maybe integralism represents the full Americanization of Catholicism. Catholics are still technically a minority (between a fifth and a quarter of the country profess the Catholic faith), but we’re now larger than any other single denomination. The desire for religious, or at least ideological, control over the nation—the conquest of the promised land—is a persistent feature of American religious culture.3 And it’s certainly not alien to Catholics, historically, even if the way we’ve absorbed it has been sort of roundabout.

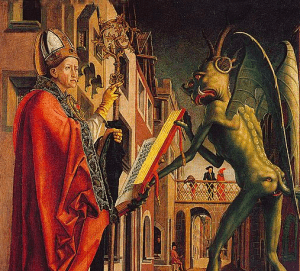

Anti-trinity

There is an old Christian triplet of sources of temptation: in the language of the Prayer-book, they are “the World, the Flesh, and the Devil.” This order is attractive to the ear, but in terms of scope, the Flesh is the weakest of the three and the World is in the middle; the Devil, obviously, being the most potent and worst. The Flesh indicates our own natural appetites and selfishness, the sort of things we’re prone to without any special influences from outside. The Devil means not just stuff like possession or witchcraft, but everything that we might call corrupt spirituality—sins like hypocrisy, fraud, and self-righteousness, with or without what we’d call a religious pretext. But I want to concentrate on that middle.

The World indicates the kind of temptations that are peculiar to the society we find ourselves in, the habitual sins of our time and place.5 “The World” is often spoken of as the opposite of “the Church,” and in some ways that’s true. But it’s also true that, insofar as any parish or diocese or multi-continental patriarchate does operate in the world as we know it, and is peopled entirely with sinners, it will take on certain qualities of the World as a source of temptation. The ambition to hold a prestigious office in the Church is a typically worldly temptation in this sense: the fact that the trappings are a cassock and a diocesan title rather than an Armani suit and a limo doesn’t make any difference, if the reason you’re interested in it is that you want to impress people and enjoy power.

The last thirty years in the US have given us a lot of examples of how churches can be “the World” just as much as secular society. The leaders of the Catholic Church or the Southern Baptist Convention have maintained stalwart ideological resistance to what they call “the world” or (more commonly) “the culture,” refusing to change their doctrines on issues like gay marriage despite political defeat. But they have also shown themselves prepared to ignore, conceal, and even punish victims of sexual abuse, if ever those victims in any way threatened their prestige and authority. That is the World in a nutshell; at least, if it is not the Devil.

St. Luke’s Temptation

When we hear the story of the temptation of Christ in the wilderness, we usually think of Matthew’s account. First, to turn stones into bread; then, to leap from the pinnacle of the temple; lastly, to worship Satan in return for “all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them.” Oddly, Luke arranges the temptations differently—Matthew’s third is his second, and the leap from the temple (with a text from the psalms to rationalize it) is his third.

Both lists seem to evoke the anti-trinity. Both seem, too, to be somehow ascending in spiritual gravity, thus presumably following a Flesh-World-Devil order. So why does St. Matthew implicitly characterize leaping from the temple as the World, while St. Luke makes the frankly counter-intuitive move of hinting that literal devil-worship is the World and the proposed feat at the temple would be the Devil? I can’t prove my interpretation of this discrepancy; I don’t even have any sources for it. However, I find it intriguing, so I’ll share it.

Leaping from the pinnacle of the temple and being borne aloft by angels would, obviously, be impressive. So impressive, maybe, that Jesus would hardly need to prove his credentials as a rabbi and a miracle-worker to the religious establishment. Looked at from this perspective, it is a clear appeal from the “point of view” of the World. As for adoring Satan in return for the kingdoms of the earth, well, it isn’t hard to see how such an act is of the Devil!

But the reverse pattern that appears in Luke is also true. (Probably both meanings are meant to be operative in the mind of the believer, just with differing emphases.) To adore Satan in return for the kingdoms of the earth is not only an obvious appeal to power, it’s even an appeal to humanitarianism—the best as well as the worst aspects of the World recommend such compromises in the name of comfort and security. And on the other hand, Jesus explicitly calls leaping from the pinnacle of the temple in expectation of a miracle “testing God” (but “he did not think equality with God something to be grasped”). It is, I think, significant that it is only this temptation which Satan tries to press home with a verse of Scripture.

Benediction

So, who cares? This may all be a neat lesson, but it’s fundamentally Sunday school material. Once again, I have no proof for my conclusion, but I’m sharing it anyway.

Most Christians believe the temptation of Christ is not just “an event” that happened to him (though it is that), but an archetype, an illumination, of how temptation as such works. I don’t think that the conflicting character the evangelists assign to the temptation to worship Satan is an accident. I think it’s a warning. Both the World and the Devil are hard at work, trying to ensnare believers to pursue dominion over the kingdoms of the world and the glory of them. Both the fundamentally earthly desire for success and power, and the supernaturally evil desire for “glory” in a far more sinister sense, converge upon this goal.

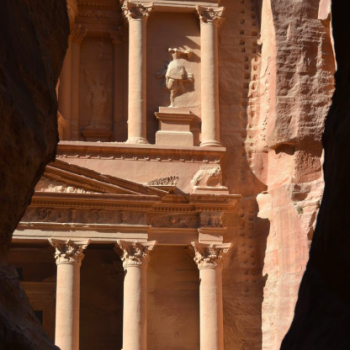

Accordingly, I am unappeasably suspicious of any political program that—like integralism—directs Catholics to seek power as Catholics, even and especially for all its honeyed words about the common good and human flourishing and the supernatural end of man. I think such programs will always prove, at best, to be stratagems for power and dignity with pretty Baroque trappings; at their worst, the haunt of the inquisitor or the Black Mass.

What Jesus showed us was utterly different. The only way to convert whole cultures that he ever commended to us was what we might call the long way around: one baptized disciple at a time. Almost the first words he says in Matthew after returning from his temptation in the wilderness are: Blessed are the meek; for they shall inherit the earth.

Footnotes

1Yes, America is not a direct democracy but a representative one, or in other language a democratic republic. Yes, you’re very smart.

2There’s a distinction here that Americans often miss. Establishment means that a specific religion, often a specific form of the religion in question, has some kind of formal legal status in the country. This can and often does coexist with religious freedom, meaning that citizens can follow any religion they choose, or none. England is a good example—the Church of England is established (it receives funds from the government, the monarch is the head of the church and in turn must be an Anglican, bishops are state employees, etc.); but nobody is forced, any more, to participate in Anglican religious rituals to enjoy full civil rights. The First Amendment guarantees both that all US citizens enjoy religious freedom, and that no religion or church can be established at the federal level.

3There were a lot of motives in the American conquest of “the Frontier” and consequent genocide of the Native American peoples,4 but the religious motive was one of them. This is especially ironic, and horrible, in that many Native American tribes and individuals were Christians long before this period, thanks to both Catholic and Protestant missionaries, some of whom enabled the genocide and some of whom did not.

4Yes, genocide is the appropriate term. A genocide does not need to “succeed” in the project of extermination it sets itself; it needs only to make the attempt to qualify. And given that a commonplace slogan of the nineteenth and even twentieth centuries was “Kill the Indian to save the man,” the extermination of Native American culture was undeniably an explicit goal.

5The seven capital sins can, in some ways, be assigned to “characteristic” sources: lust, gluttony, and sloth to the flesh, avarice and envy to the world, and anger and pride to the devil. However, these correspondences aren’t total. Avarice can be a sin of the flesh, for instance, if it’s expressed in an excessive attachment to some possession that only has meaning to you and doesn’t confer any social status or power. The “seven sins” and “three tempters” are two basically different ways of analyzing sin, and the patterns they form are complex.