Love Thy Neighbor

Full disclosure: this post is not an in-depth look at the sorrows of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Those are a subject I don’t know a lot about, except in very general terms—and “bad things make Jesus sad,” while true, isn’t something I can write a worthwhile essay about. I don’t think.

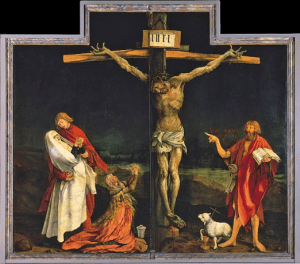

But, June is Pride Month. Which means Catholic Twitter is swarming with people talking about how un-Christian pride celebrations are, pride is a sin, etc., and saying we need to reclaim June as the month of the Sacred Heart. (The Solemnity of the Sacred Heart nearly always falls in June; it’s always on the third Friday after Pentecost, which typically falls in May or early June, this year on June 5th.)

This is, of course, terribly funny: the notion of any creature proposing to defend Omnipotence usually is. So Catholic Twitter is also swarming with people in this set of people’s replies, jeering at them. I’ve done it several years running, and this year is no exception. Of course, when I actually refer to it as “jeering,” I suddenly find myself a little bit less comfortable with it; not because attempts to defend Omnipotence deserve respect (they don’t), but because my neighbor deserves respect. Or, if deserves is felt to be too much, I am at any rate under orders to respect my neighbor—that being how the Golden Rule works.

The Meaning of Pride

I do celebrate Pride myself, in a few different ways (and most of them are ways I don’t even have to go to Confession over). I toyed with dropping the celebration a few years ago, as I was tiring somewhat of LGBT activism and the whole business of being, so to speak, a Public Gay; that year, as it happened, was 2016. After June 12 of that year rolled around I definitely discarded any idea of not celebrating Pride.

Most of the Christian objections to Pride that I’ve come across have been obviously bad-faith pretenses at not seeing the difference between “pride” as a sin and “pride” as a sense of self-worth and human dignity. (Oddly enough, I’ve come across these objections more often than I’ve come across objections to the public lewdness that does often form a part of Pride celebrations—though that may reflect the circles I travel in more than how common either objection is.) I don’t propose to waste my time on people who raise bad-faith objections, but there are a handful of people who raise this objection in good faith, and I’d like to speak to them.

Pride celebrations started after the Stonewall riots, which started the modern gay rights movement. They mean a lot of different things, and include a lot of different events. Some of these events are, shall we say, adult, but most aren’t; it is quite true that most Christians will probably feel the need to avoid those Pride events, but in my experience these are very much the exception, and (especially since LGBTQ adoption became common) a lot of Pride celebrations are designed to be as family-friendly as any other city summer festival.

Because at its core—and I’m going to say something here that’s a little controversial within the LGBTQ community, but I think it’s true—Pride isn’t about sex.1 It’s about the fact that we have human dignity, just like heterosexual, cisgender people do. That we don’t deserve to be thrown out of our homes, or turned away from public institutions, or brutalized by the police; all of which were issues that plagued gay people in 1970, back when Pride celebrations started, and most of which continue to be problems for us in some regions and contexts. I said above that “bad things make Jesus sad” isn’t a slogan I can do much with; but I do believe these injustices and cruelties wound his Heart, because he cares about us. We’re human: that’s all it takes to be loved by God.

How any person or group celebrates Pride is doubtless open to critique (though, do note: you probably aren’t being asked for your critiques, so think twice before offering them). But celebrating Pride in and of itself is, in my opinion, completely open to Catholics,2 and Pride can be important and special to LGBTQ Catholics like me.

Love Thy Brother

If you’ve come here doubting whether Pride is legitimate at all, I’m guessing you don’t feel ready to attend any festivities. That’s fine; even people like me pick and choose what to go to. For instance, I don’t generally attend Pride parades, not out of any moral objection but because I find parades skull-crushingly boring.

But if you’re willing to take a word of advice—not that I’ve been shy with it up to now!—whatever else you do, don’t get worked up about it. It isn’t worth it. Culture war stuff is pretty much never worth your time, and, nine hundred and ninety-nine times out of a thousand, it makes it harder to love people, not easier. Because when you’re waging a war for a culture, what that means in practice is training yourself to see other people, people who aren’t on Your Side, as the enemy. And that isn’t what the New Testament teaches us to do. There is an enemy to be found in its pages; but that enemy isn’t other people. Neighbor—friend—fellow citizen—brother—these are the words the New Testament harps on when speaking about other people, especially within the Church, but even outside it.

And the brute fact is, you’re sharing the Church with LGBTQ people. A lot of us have been baptized; statistically, at least some of us are going to be following you into heaven, or waiting for you when you get there. Might as well get cozy.

Footnotes

1For LGBTQ readers who may chafe at this take (since de-sexualizing oneself is often a “respectability” tactic for gaining acceptance), I don’t mean our sexuality is irrelevant to Pride; that’s obviously false. What I mean is, Pride is for every sexual and gender minority, and that includes people who—whether due to private convictions, an asexual orientation, or just preference—don’t engage in any kind of sex.

2To take a partly parallel example, a lot of Mardi Gras or St. Patrick’s Day festivities involve plenty of things Catholicism considers sinful or excessive, especially regarding alcohol. But I’ve never heard any Catholic say that we should avoid these celebrations in and of themselves: only that we should choose what to go to judiciously (or maybe substitute our own events) and mind our own behavior.