A Summer Festivus

How should Catholics respond to Pride festivities? A classic question for the apologist, which we can only assume slipped the minds of the Apostles, else it would surely be addressed in the New Testament.

In order to give any sincere, intelligent answer to this question, we need to know what Pride is. Social media abounds in Catholics who are eager to tell us that pride is one of the seven capital sins.1 Luckily, words only ever mean one thing. Catholics never refer to themselves as proud of anything, nor do we exhibit the sin of pride. What’s more, the month of June is devoted to the Sacred Heart, and should be reclaimed for that, because when you devote a month to a thing, all other associations of that month disappear. Case closed!

I’ll now pry my tongue back out of my cheek and try to give a real answer. For it, we’ll need a short history lesson about The Gays. (If the thought of that makes you ill and you prefer to argue about historical facts without knowing them, the sections headed like this in rainbow type are the ones discussing it; moral and political claims that depend on and are backed by those historical facts resume at the section titled Humanæ Vitæ.) Let’s get started.

Hey, I didn’t say I’d keep my tongue out of my cheek.

From Stonewall …

From the nineteenth century down through the 1960s, gay bars were illegal in many countries, including the US. (Weimar Germany, or at least Berlin, was a prominent exception.) But of course, underground establishments catering to queer2 people sprang up. These bars were largely under the control of the mafia, who typically bribed the authorities to leave them alone. One such bar, fairly small and cheap, was the Stonewall Inn, located in Greenwich Village on the lower west side of Manhattan. It was especially frequented by young, homeless gay men (some of them hustlers) and trans women.3

In June of 1969, the NYPD didn’t receive its bribe. They therefore raided the Stonewall … the night after Judy Garland’s funeral. Grief, plus the other exasperations of being a queer person in the ’60s, had Greenwich Village at a quiet seethe already, and the raid did not go according to plan. The patrons of the bar fought back, and the situation escalated into a full-scale riot, which lasted for days. It was the birth of the modern gay rights movement. The following year, the anniversary was chosen as the date of the first Pride parade: a declaration of queer people’s right to live, work, and socialize, free of harassment from law enforcement and the public at large. They did not deserve to be shamed for who they were, and would not implicitly accept that shame by hiding any longer.

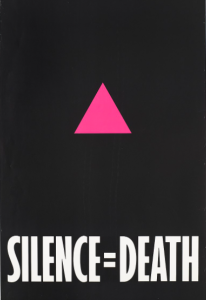

… To St. Vincent’s

About a decade later, the AIDS pandemic began. It hit the queer community the hardest, at least in the beginning; to this day it is widely perceived as a “gay disease” (though in fact it is sub-Saharan Africans, of all orientations, who currently have the worst of it). This was met by the White House with a resounding chorus of absolutely nothing. C. Everett Koop, the Surgeon General under Reagan, was actively prevented by the administration from addressing the crisis; he finally just disobeyed his instructions and, in 1988, mailed information on the disease to every household in the country, in a desperate and somewhat successful attempt to educate the public.

In treating HIV, the Catholic Church did better than I’d have dared to hope for. Greenwich Village was also home to St. Vincent’s Hospital, run by a Catholic order called the Sisters of Charity, and it became one of the earliest and most important centers for the study and treatment of HIV. There were complaints that the staff could be more than a little judgmental; however, no one was refused entry, which was especially important in the early years of the outbreak—for a long time, HIV+ people could be turned away from hospitals (to say nothing of how many were disowned by their families).

For this reason, throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Pride demonstrations typically memorialized AIDS victims too. This has become less true as, thank God, HIV treatments have improved, especially with the approval of the “vaccine” Truvada in 2004. Nonetheless, a generation of queer people were decimated by the disease. And not only that, they were faced throughout the ’80s with a government that would not just do nothing, but would obstruct officials who tried to counteract it, even when doing was obviously part of their job description. And in this regard, the Church sinks back toward my low expectations of her. Catholics largely aligned themselves with the GOP over the ’80s, as the only party in which being at least nominally pro-life was accepted. But the GOP seems to have influenced Catholics far more than vice versa, since plenty of Catholics today who pride themselves on their orthodoxy are entirely ignorant of—or will even contemptuously reject—Catholic doctrine on questions like usury,4 unions, capital punishment, the universal destination of goods, and the preferential option for the poor.

Humanæ Vitæ

The right to freedom from police harassment, the right to associate with whomever we choose, the right to have threats to our well-being treated seriously and not ignored, the right to have our deaths known and mourned: these are why Pride festivals exist—as a matter of historical fact, not a contrivance of political convenience. (Indeed, if we were trying to talk about Pride in Latin, the word to reach for would not really be superbia, the name of the capital sin. It would be dignitas, one of the core moral and social values of ancient Roman society.) Pride is a statement that we will not surrender our health, our self-worth, or our civil rights to people who hate or despise us, even if they try to conceal it behind a veneer of moralism. The rainbow flags and go-go boys and so on that may be present at this or that Pride event, that’s all decoration. The point is not in those things: it’s in our mere public presence. We’re queer; and we’re still here.

Which suggests that really, Catholics ought to see Pride as a pro-life festival.

Granted, it doesn’t have to do with abortion. But the point of the “culture of life” St. John Paul II sought to promote was that being pro-life is not solely or even chiefly about abortion. The dignity of the human person, at all stages and of all kinds, is its concern. Human dignity as such, wherever it is attacked, merits defense, and wherever it is hurt, merits healing. That’s why issues like capital punishment or the injustices of the prison system are properly very pro-life concerns. And given the way homophobia keeps breaking out in violence—from the actions of individual criminals like Omar Mateen, to state-backed violence like what just hit the books in Uganda—opposing homophobia is a pro-life issue too. Unless of course, as many pro-choice advocates like to say about us, our claim to be pro-life really did only mean that we were pro-birth.

As for the Profound Insight that the name of these festivities Really Says Something about LGBTQ people, that’s beneath serious reply. This is true for the same reason that it would not be worth my time to contend with a fanatical anti-Catholic apologist who firmly maintained The feast of the Assumption is named after the Catholic assumption that it happened. Any native English speaker, if they think honestly about the question for even a few seconds, will recognize that pride in the sense of “self-worth” is a perfectly normal usage. Ideally (and God willing, some day in reality), the same why-even-answer-that would go for the use of terms like queer, gay, and so on, and for respecting trans people’s preferred pronouns; but that’s a slightly different topic, so I’ll leave it to one side for now.

The Voice of Him That Crieth in the Combox

I can all but hear the dutiful Catholic’s rebuttal:

But but but! What about all the sexual immorality? You make such a virtue of accepting Catholic teaching about homosexuality—which is the abject least you should be doing, and you’ve admitted many times to not actually observing this teaching you “accept”—and trot out all this stuff about how terrible Catholics are, for supposedly being mean to “gay” people. Yet can’t you admit that Pride festivals do in fact celebrate sexual sin—oh fine, that the “identity” Pride festivals celebrate is rooted in sexual sin? And that people gather at them precisely to indulge in sexual sin and in public impenitence for it? Come on, this is just acknowledging plain facts! Can you kindly give us that at least!?

As a matter of fact, no. I’m not even giving you that. However, the argument here (regardless of the motives that prompt a person to use it) draws close enough to reason that I think it deserves reply, which I’ll give in Part II.

Footnotes

1Also known as the seven deadly sins (the other six being envy, anger, sloth, greed, gluttony, and lust). Capital is a slightly better word for them: the idea is that they are the “heads” (Latin capita), or categories, under which sins fall, not that these seven sins are specially evil.

2Here and throughout, I’m using queer in the academic sense, i.e. as a reclaimed umbrella term for LGBTQ people in general. Not all LGBTQ-identifying people like this usage, which is understandable; however, and with apologies, I’ve settled on using queer as one of the few concise and euphonious synonyms for, well, LGBTQ.

3Hustlers are gay male prostitutes. Trans women were mainly referred to at the time as transvestites, by themselves as well as others; the difference between transvestism as we use the word today and transgender identities had not been clearly articulated.

4Many persons mistakenly believe that the Church’s teaching on usury was repealed at some point. It was not. What did happen was, interest on certain types of loan was determined to be a different kind of thing from usury, which can only be charged on what are called mutuum loans, which are properly an act of charity; a simplified explanation is, it’s wrong to charge interest on a mutuum loan because it’s wrong to profit off charity. Usury is inherently sinful, whereas interest on non-mutuum loans can be licit (sinful if the rate is excessive, yes, but that isn’t what makes it usury). I am not nearly good enough at economics to explain Catholic doctrine on this fully, but I can recommend this extensive FAQ post from the blog Zippy Catholic on the subject, which is also available as an e-book and .pdf file.