I’m Sorry, Christ the What?

The snake is not always an evil creature in Scripture. True, it is associated—as a symbol; snakes are God’s creatures, they are not literally demoniac—with what most Christians believe was an appearance of Satan in Genesis. At the other end of the Bible, Revelation speaks of Satan as “a great red dragon”: dragons were traditionally thought of as something like snakes to the nth degree.

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed

With the Sun by William Blake (one of two

paintings of that title), ca. 1800-1820.

This was all a specific turn within a much older Ancient Near Eastern tradition of talking, thinking, and writing about snakes as symbols. They were not uniformly considered good: in the Gilgamesh, a hostile serpent snatches away the blossom of immortality from the hero, before he can bring it home to his people. Yet the snake was often a symbol of positive attributes: wisdom was a common meaning assigned to them, as was rebirth (thanks to their habit of shedding their skins). Like most symbols, serpents were polyvalent, i.e. “having more than one meaning.”

This is neatly illustrated in a few episodes of Moses’ career. One of the miracles God specifically gives him as a sign for Pharaoh is the ability to change his staff into a serpent (one than proceeds to eat the staves of the Egyptian sorcerers who do the same thing, which is hilarious). Then there is the famous origin story of the Nechushtan [נְחֻשְׁתָּן]. You may not think you’ve heard of this, but you’ve heard of it. It was evidently something roughly like the caduceus, Hermes’ staff in Greek myth:

The soul of the people was much discouraged because of the way. And the people spake against God, and against Moses, “Wherefore have ye brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? for there is no bread, neither is there any water; and our soul loatheth this light bread.” And the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people; and much people of Israel died.

Therefore the people came to Moses, and said, “We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord, and against thee; pray unto the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us.” And Moses prayed for the people. And the Lord said unto Moses, “Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live.” And Moses made a serpent of brass,1 and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, when he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived. —Numbers 21.4b-9

A bronze snake adorning the capital of a

column in the Basilica of St. Ambrose in

Milan; the sculpture was donated by the

Byzantine Emperor Basil II in 1007.

Photographed by Giovanni Dall’Orto in

2007 (source).

The name Nechushtan (or Nehushtan) for this object, apparently a pun on the Hebrew word for brass, n’chosheth [נְחֹשֶׁת], comes to us from a later period in Israelite history. As we know, the whole “monotheism” thing was a tad touch-and-go in pre-Exilic Judaism; apparently, the brazen serpent had not only been preserved along with other artifacts from the wilderness period, but had by the reign of Hezekiah become an object of idolatry. Maybe some of the more nationalist citizens of Judah could get behind the rejection or downplaying of foreign gods under Hezekiah, but thought his henotheist or monotheist outlook was simply too silly to contemplate. Come now, Your Majesty, this is a modern, sophisticated kingdom; nobody just has one god; it’d be like—oh, Your Majesty has had the Nechushtan ground up. Uh. Yes, that’s very … nice.

The New Testament also mentions snakes a few times. As in the Hebrew Bible, these allusions are usually negative but not always: Christ instructs the Apostles to be “wise as serpents and harmless as doves” in Matthew 10, for instance. There is also a tradition (picking up on Mark 16.18, part of the “Longer Ending“) that someone once tried to poison St. John the Apostle, but when he blessed his drink, the poison coalesced into a small snake that slithered out of the cup—which is why, as St. Peter’s conventional symbol is a crossed pair of keys or St. Andrew’s is his X-shaped cross, the symbol of St. John is a chalice with a serpent coming out of it, or coiled around it.

But the most important positive allusion to snakes comes in Jesus’ dialogue with Nicodemus.

John 3.14-21, RSV-CE

A memorial of the brazen serpent, created

by Gian Paolo Fantoni, located on Mount

Nebo (said to be where Moses was buried).

Used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

a“As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of manb be lifted up, that whoeverc believes in him may have eternald life.”

For God so loved the world that he gave his onlye Son, that whoever believes in him should not perishf but have eternal life. For God sent the Son into the world, not to condemng the world, but that the world might be savedh through him. He who believes in him is not condemned; he who does not believe is condemned already, because he has not believed in the namei of the only Son of God. And this is the judgment, that the light has come into the world, and menj loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil.k For every one who does evill hates the light, and does not come to the light, lest his deeds should be exposed.m But he who does what is true comes to the light, that it may be clearly seenn that his deeds have been wrought in God.

John 3.14-21, my translation

a“And exactly as Moses lifted up the snake in the desert, just so the Son of Manb must be lifted up, so that everyonec who trusts in him should have eternald life. For just as God loved the world, so he gave his only-begottene son, so that everyone who trusts in him should not be destroyed,f but have eternal life. For God did not send his Son into the world in order to judgeg the world, but so that the world should be savedh through him. He who trusts in him is not judged: he who does not trust is already judged, because he has not trusted in the namei of the only-begotten Son of God. This is the judgment, that the light came into the world and peoplej rather loved the dark than the light, for their works were oppressive.k For everyone who practices pettinessl hates the light and does not come to the light, lest his works be cross-examinedm; but he who does the truth comes to the light, so that his works should be manifested,n that they are worked in God.”

Textual Notes

a. [Paragraph-ization]: A couple of posts back, I mentioned that first-century writing didn’t have capital letters. It didn’t have a lot of things! Three more are modern chapters and verses2 and quotation marks. Quotation marks weren’t invented until the mid-sixteenth century. They had a predecessor, marginal marks that looked like these < >,3 but they were optional. The modern versification of the Bible is a little bit older; it goes back to Stephen Langton, a thirteenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury who was the principal author of the Magna Carta (and also probably wrote the sequence Veni Sancte Spiritus).

Sculpture of Archbishop Stephen Langton

from Canterbury Cathedral, photographed

in 2010 by Wikimedia contributor Ealdgyth

and used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

I bring this up because the RSV editors’ decision that Jesus’ speech to Nicodemus ends with the end of verse 15 is not actually part of the text. It’s by no means a ridiculous interpretation, but it is an interpretation, and one that I don’t see much rationale for.

John 3.15-21, as well as vv. 31-36, are well-known among translators for being a little contentious. Some people think they are the author providing a kind of “narrator’s commentary” to the proceedings; others attribute them to Jesus and St. John the Baptizer, respectively; others think that vv. 15-21 are Jesus, but that vv. 31-36 are “the narrator.” (I don’t think I’ve seen anybody argue it the other way around, that vv. 15-21 are narration but vv. 31-36 are St. John. You certainly could, though—be the change, etc.)

The reason I’m disposed to fall in with the “Jesus and St. John the Baptizer both are saying these things” interpretation is that it seems more consistent than the others. While do we get occasional asides from the author (or redactor) in John, like 13.1, 19.35, or 20.30-31. But these are the exception, and they don’t blend into the rest of the text like vv. 15-21 and 31-36 here do: they’re contextualizing remarks, not theological commentary. You could maybe argue that the prologue, 1.1-18, fits the bill, but that comes right at the beginning, I don’t think the same rules apply—introductions don’t necessarily read like the main body of a text does. For a text to break its own flow midstream, though, is quite unusual; doubly so, I’d argue, for a book as carefully and deliberately written as John. Nor, allowing for the distinctive Johannine idiom, are they saying things that are out of character for either figure.

b. Son of man/Son of Man: The note here is not about the capitalization of “Man” in my version, nor about the phrase Son of Man (a phrase with prophetic and apocalyptic undertones, but we’ll leave that for another time). No, this is just my regularly-scheduled gripe about English. The Greek rendered “man” here, anthrōpos [ἄνθρωπος], would be better translated “person” or, possibly, “human”; there’s a different word (anēr [ἀνήρ]) that means “man” in the sense of male, and which can also mean “husband.” However, the phrase “Son of Person” sounds like someone invented it to make fun of ChatGPT, and “Son of a Person” is not much better! The same goes if you swap out person for human in either example. The last alternative I could think of was the phrase “Son of Humanity,” which I guess doesn’t sound terrible, but feels really off to me somehow, in a New Age kind of way that I can’t put my finger on. Accordingly, and with the caveat that I’d be very willing to entertain arguments that “Son of Humanity” is a great translation actually and I’m the weirdo here, I’ve gone with the slightly old-fashioned “Son of Man.”

I wanted a picture of Aquarius to go with the

“New Age” allusion, and stumbled on this li’l

guy from a French book from the 1400s

—a testament to the Medieval love of li’l guys.

c. whoever/everyone: The difference is small, but I do prefer my translation due to what is almost certainly a technicality. Or rather, it is certainly a technicality, and almost certainly no more that.

The Greek uses a construction we don’t have in English, a substantive participle: don’t worry about what that is, you just need to know it can act like a noun, including being modified by adjectives. Now. The word whoever is what’s called an indefinite pronoun,4 meaning it has no specific person it’s referring to; these tend to be used in gnomic statements, hypotheticals, questions, that kind of thing. That isn’t quite what the text conveys, though. Greek does have an indefinite pronoun, tis [τίς], but that word isn’t used here; it’s inserted into the English for readability. The text takes its substantive participle and modifies it with the adjective pas [πᾶς], better known to us as the prefix pan- or pant-, meaning “all, every.” All is an indefinite adjective, but every is a definite one: they refer to the same quantity of things, but all does so by putting them in a single box, so to speak, while every does so by considering each item individually. (That may make using “everyone” as my translation seem tendentious on my part, but in order to translate pas as “all” here, I’d have had to recast the sentence in the plural, and the Greek sticks with the singular.)

Obviously, the sense of the text does still make it open-ended in one way—it isn’t offering us a roll-call of the elect! But the resonances of whoever versus those of everyone are subtly different. Everyone has just a shade more personhood, more particularity, in it; you could address a crowd “Hey everyone,” but you couldn’t address them “Hey whoever” (that instead suggests “whoever [what I’m about to say may apply to]”). This same distinction is reflected in the pious saying that Jesus died not only for all men, but for each man: the difference in atmosphere between a generic amnesty that applies to a hundred criminals, and each of those hundred criminals being individually pardoned, is colossal.

d. eternal: This represents another one of those Greek words that makes me crabby, and it’s all C. S. Lewis’s fault. The Greek is aiōnios [αἰώνιος], a derivative of aiōn [αἰών], meaning “life” but normally with the sense of “lifetime.” It thus comes, through the meaning “generation,” to mean “world” in the temporal sense, as when we speak of “the ancient world.” (Surprisingly, this does mean that the archaic prayer-book expression “world without end” is actually a reasonably good translation of eis ton aiōna [εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα], often translated “forever.”) All this, I learned from Lewis’s Studies in Words (a book I cannot recommend highly enough to anyone who wants to get a sense of how language works and develops). But, long story short, this means that aiōn and its derivatives are one of those terms that don’t fit neatly into my preferred translation model. Boo!

e. only/only-begotten: I’m mildly puzzled by the RSV’s choice here. The word they translate “only” is monogenēs [μονογενής]. That’s not what monogenēs means. Monos [μόνος] means “only”; monogenēs means “only-begotten,” or “one-of-a-kind,” which I guess you can stretch into rendering as “only” if you really want to, though what you’re going to do with monos in that case beats me.

f. perish/be destroyed: “Perish” is a conventional, and obviously natural, way of using and translating the passive voice of the verb for “to destroy,” apollümi [ἀπόλλυμι]; I’ve just opted for something a tad more literal. However, I did want to highlight apollümi, for the mere fun fact that it is the basis of the name Apollyon: Apollüōn [Ἀπολλύων], “Destroyer.” (Though this is unlikely on linguistic grounds, there were ancients who believed the name “Apollo” was derived from apollümi as well, with the fanciful etymology that it referred to his deadly arrows, traditional symbols of disease.)

g. condemn/judge: The word here is krinō [κρίνω], “to judge,” with about the same implications as the modern English term. If I may be catty for a moment, it’s rather funny that so many translators don’t like translating the verb “to judge” as “to judge” when the connotation is plainly negative. This is popular English usage; it was common Greek usage; seems like a match made in heaven, right? But apparently, not all Christians are comfortable with talking about judgment like it’s a bad thing, so we need to change the verb to “to condemn.” It’s not wrong, but it’s introducing a verbal distinction in the English that not only does not exist in the Greek, but is not necessary to understand the English; to me, that seems kind of telling.

h. saved: This verb, sōzō [σῴζω] (and its derivative sōtēr [σωτήρ], an agent who does the action of sōzō-ing), is one of the most important in the New Testament. It is most commonly rendered “to save”; and, say it with me now: That’s correct, but.

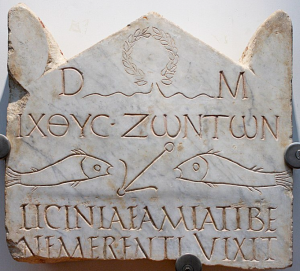

Third-century Roman funerary stele.

Likely Christian, based on the fish and

anchor (both Christian symbols); the

Greek text reads “fish of the living.”

You see, in both Greek and Latin (and therefore the Romance languages), “to save” and “to heal” are generally the same word, or at any rate there is some single word that covers both meanings. The same goes for related terms like “salvation” and “health,” or “savior” and “healer.” (In Italian, for instance, salute can mean “health,” and in that sense be used as a greeting, or “salvation.”) And to make the linguistic situation still more complex, sōtēr was one of the common titles of the Cæsars: as Augustus had brought a close to a century and a half of recurring civil wars, hailing him as “Healer” was fairly natural, and the title stuck after his death, rather inconveniently for ancient Christians who didn’t like sounding seditious when they called Jesus Christ, the Son of God, their Savior—in Greek, Iēsous Christos Theou Hüios Sōtēr [Ἰησοῦς Χριστός Θεοῦ Yἱός Σωτήρ], forming the acronym IChThUS [ἸΧΘΥΣ], “fish.”

But English doesn’t want to play nice with the other languages this morning. The closest it comes to this overlap is the similarity between the words save and salve. And even that is a false cognate! “Save” comes from Latin via French, whereas “salve” is part of our Anglo-Saxon heritage5; plus, it isn’t like the word “salve” gets a huge amount of usage, especially in theological contexts.

We do love an Anglo-Saxon heritage around

here, though, don’t we folks! (Just please

don’t get the fashy kind of weird about it)

The point of all this is that there are several places where it is, and possibly should be, unclear whether the text means sōzō in the healing sense, or sōzō in the saving sense. “Thy faith hath saved thee”: does this mean Your faith has healed you? In this text, I think a double meaning is perfectly plausible.

i. the name: There are two divides here, an ancient/modern one and an Anglo/Semitic one, that make us apt to be confused or just stumped by the Biblical treatment of names. A lot of us probably think of it as no more than part of the rhetorical penumbra of religion, and pay no further attention; maybe, at most, we bear in mind the idea of preserving one’s “good name,” i.e. reputation.

This was not how most ancient cultures thought, and is not how most Semitic cultures think, about names. Rather, a name is, or is part of, a person’s self, their identity. To know a person’s name is to have some kind of intimacy with them, or power over them; one of the important early parts of most exorcisms is the exorcist forcing the demon to disclose its name. The fact that God reveals the Tetragrammaton to Moses is a huge deal, far more so than the theophany in which it takes place. It is doubtless no coincidence that, thirty chapters later, God consents to reveal still more—I will make all my goodness pass before thee, and I will proclaim the name of the LORD before thee … and thou shalt see my back parts: but my face shall not be seen.

The Tetragrammaton, as represented in

the Paleo-Hebrew script and in the

Aramaic square script (now widely called

“the Hebrew alphabet” after its chief use).6

In this light, to “not believe” or “not trust in the name of the Son of God” is something more than disrespect. It is a form of very personal rejection, one that involves an implicit statement hardly short of “Who you are, everything about you, is worthless to me.”

j. men/people: This represents the plural of anthrōpos (see note b. above). It is correct to translate it “man,” as it is grammatically masculine; it is at least equally correct to translate it “person” or “human,” as its gender was mainly formal, like the gender of the English word “man” used to be.

k. evil/oppressive: This word, ponēros [πονηρός], has come to mean “evil” in the moral sense in modern Greek, but the root is actually a verb that has to do with hard work. I gather it passes from this meaning, through an implication of being exhausting, toilsome, or painful, to “oppressive,” and thence toward the current meaning. It is possible that when Jesus spoke here of ponēra ta erga [πονηρὰ τὰ ἔργα] or “evil deeds,” he was expressing something more akin to disgust—that these transgressions were “a weariness to think about,” so to speak.

l. does evil/practices pettiness: Here we get yet another case of the RSV-CE’s translators making the text both less vivid and less literal for no clear reason. “Does evil [things]” is of course a tolerably good rendering of phaula prassōn [φαῦλα πράσσων], but there’s distinct room for improvement. The verb typically translated “to do,” poieō [ποιέω]—which originally meant “to make”; you can see the same shift/expansion of meaning in the Latin facere—is a different one from the root of prassōn, which is a relative of our word “pragmatic”; it’s a more specific word, along the lines of “practice” or “accomplish.”

And phaula is even more interesting. Here as with ponēros, its modern Greek descendant gives the word a strongly moral sense, but the ancient word has not reached that stage. It comes from the same Indo-European root as the Latin name Paulus, which literally meant “small.”7 In the Latin this meaning was retained. In Greek, the significance drifted toward “common,” “poor,” “worthless,” “sorry” (as in the phrase in a sorry state), and even “mean.” Petty seemed like the sense that most nearly captured the rest, so I picked it up in my translation. What strikes me, though, is how much less this textual note and the last one have of the aura of the mystical or the apocalyptic that we associate with John. The note struck here is almost one of disdain for evil, something evocative less of the holy war between St. Michael and the dragon than of the scornful laughter of Psalm 2.

m. exposed/cross-examined: Here too we have a fascinating word choice: elenchō [ἐλέγχω]. It can mean “to shame”; it could also indicate questioning someone or ferreting out the truth. Socrates’ technique of asking questions in Plato’s dialogues was called his elenchus, and Aristotle titled a whole subdivision of his manual on logic Sophistikoi Elenchoi [Σοφιστικοὶ Ἔλεγχοι], “Sophistical Refutations” (i.e. exposures and rebuttals of fallacies). But besides the link to or echo of Greek philosophy, this accents one of the recurring themes of the Gospel of John, one I touched on back in December, in my post for Gaudete Sunday.

The Synoptics each place Holy Week in nearly their last two or three chapters, barring a very last devoted to the Resurrection; they’re not exactly biographies, but they are memoirs. John is structured quite differently. Fully half of it (chapters 12-20) takes place in Holy Week, according to its own sequence of events, and that’s before we account for possible thematic rearrangements of the material. This fits into the theme that dominates the entire book, first becoming explicit in 1.7, and recurring again and again, all the way through its last appearance, 21.24, with just one verse more in the book.

Ikon of Christ washing the disciples’ feet,

written in 16th-century Pskov in the

Russian Baltic (then independent).

That theme is the trial of Jesus. As mentioned, already in the prologue (1.1-18) hints are being dropped. A witness (St. John the Baptizer) giving testimony under cross-examination from officials of the Judaic high court is how we open the action of the book; not long thereafter, direct testimony (again from the Baptizer) of signs from heaven, promptly followed by a sign here on earth (the miracle at Cana), and then a third sign of a different kind, the cleansing of the Temple. That instantly evokes Holy Week, both as its second dramatic action—the Triumphal Entry being the first—and as the occasion on which he uttered the phrase that was made the basis of his conviction: “Destroy this Temple, and in three days I will raise it up.”

After that, the themes repeat in varying patterns. A total of seven miracles in chapters 2-11, as if to present “exhibits A through G.” Interspersed with these is more testimony, both from him and from those he heals; still he is being questioned, the officials remain uneasy with him. Finally, with the arrest and formal trials before first Annas and then Caiaphas, the thematic trial reunites with the actual trial. Verdict—sentence—thus we are carried through the Passion, death, and burial, to the Resurrection.

Yet even here, theme is easy to pick out. The Apostles are commissioned as witnesses; their power of forgiving or retaining sins is plainly akin to the powers of a civil magistrate to examine, discipline, and pardon; one of the key witnesses requires some up-close-and-personal persuasion, presumably for the benefit of future judges. Jesus re-performs one of his miracles, like it’s an inside joke—which, there’s really no reason a miracle shouldn’t also be an inside joke, or none come to mind—thus bringing the total to nine and the “Exhibits” up to the letter I. Almost the very end of the book is another cross-examination, though this one reinstates rather than shaming St. Peter; and sentence is pronounced over Peter as well, though there will first be a long reprieve.

But if this is a trial, who is the judge? That’s perfectly simple. It’s you. You, the reader, are being presented with the evidence and invited to form a verdict: What then shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?

n. clearly seen/manifested: The Greek here is a single verb (phaneroō [φανερόω]), meaning “to disclose, make manifest, make visible”; if you’ve heard of the Phanerozoic period of the fossil record, it is so named because the life that made the fossils made fossils big enough to be visible. (That verb is a derivative of phainō [φαίνω], “to shine,” which appears in the terms Epiphany and Theophany.) As elsewhere, I’m going to prefer a single term rather than a verb-adverb combo, if I can help it.

1There’s some variation here in translations of the metal used: the King James opts for brass, as do a few others, but a majority of translations say bronze. A copper alloy of some type certainly seems indicated.

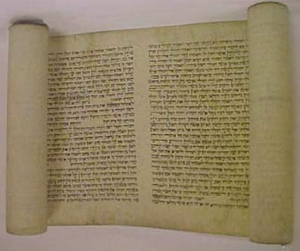

2It did have distinct sections, a little bit like paragraph breaks: parashiyoth [פָּרָשִׁיּוֹת] in the Old Testament and kephalaia [κεφαλαία] in the New (the singulars are parashah and kephalaion). These divisions were created for use in lectionaries; common practice in both synagogues and many churches is to go through their respective Bibles in a cycle, either yearly or over a set number of years. (If you’ve heard of Jewish boys preparing for their Bar Mitzvah practicing their “Torah portion,” these parashiyoth are what that’s referencing.) I don’t know whether the Church used parashiyoth in deciding on lectionary readings; the parashiyot have existed since at least as far back as the Dead Sea Scrolls. As for the kephalaia, there tended to be many more of these per book than chapters in the modern system—not that they were necessarily shorter, but that they were placed on different principles: e.g., in Matthew chapters 5-7 are devoted to the Sermon on the Mount, while chapter 8 is devoted to five miracles (and some remarks made in conversations); the kephalaia preserved by the fourth-century writer Eusebius show chapters 5-7 all under one kephalaion, while chapter 8 gets five, one for each miracle.

3I’m struck by the similarity between the shapes of < >, « », and “ ”, enough to wonder whether they’re related. That second set of marks (called guillemets) are or were used as quotation marks—sometimes only for specialized purposes—in a great many languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Finnish, German, Greek, and multiple Romance, Slavic, and Turkic languages.

4In this instance, okay grammarians? Come at me. Plus, the reason we use it as an interrogative in the first place is because it’s indefinite, so why don’t you cry about it.

5I was unprepared for it to be this way around—I could have sworn we got “salve” from the Latin salvare and that “save” was from some Germanic root, but, nope! It’s the reverse.

6 The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet developed out of the Phoenician, or was a variant of it. Pre-exilic writing in Palestine is in this script. During the Exile, however, the Jews learned and adopted the Imperial Aramaic alphabet—Aramaic was a lingua franca to the east and southeast of Jerusalem, quite as much as Greek was to its west and northwest—and brought this back with them under Cyrus (or, if they stayed in Babylon, kept it anyway). Interestingly, for some time, there was a Jewish custom of writing manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible in the new square script, but to write the Tetragrammaton itself in Paleo-Hebrew letters; however, this finally dropped out, and the only group of people who clung to the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet were the Samaritans.

7Yes, this does in fact mean that the gospel was spread all around the Mediterranean under the leadership of Rocky and Shorty.