John? Mark? John Mark?

Mark is by far the shortest of the canonical Gospels, and so, to suit the fifty-odd Sundays of the lectionary, it requires a bit of in-fill accordingly. The third, fourth, and fifth Sundays of Lent all feature readings from John in Year B (respectively: 2.13-25, the cleansing of the Temple; 3.14-21, part of Jesus’ dialogue with Nicodemus*; and 12.20-33, Jesus’ prediction of his imminent Crucifixion during Holy Week)—our return to Mark will come with Palm Sunday, when its narrative of the Passion will be read. There’s also a period over the summer, in August I think, where the “Bread of Life” discourse is read over a course of a few weeks.

EDIT: When first published, this paragraph incorrectly stated that the Gospel for the Fifth Sunday in Lent was John 11.1-45, which recounts the resurrection of Lazarus. My apologies for the error.

It’s no secret that John is my favorite Gospel. My final Greek class in college was an independent study of John, during which I learned that, while its Greek is quite elegant in its own way, “its own way” is quite a strange idiom. It reminds me, faintly, of the high Calormene style C. S. Lewis put in the mouths of Aravis and Emeth: clearly not the sort of rhetoric native to English, but clearly reflecting a long and lofty tradition of its own. Given my particular liking for it, it’s very tempting to introduce it in the same detail I devoted to Mark, but for now, I’ll hold off, making only a few introductory remarks.

Emeth the Calormene, as illustrated by

Pauline Baynes for The Last Battle

(1956). Image provided for under fair use.

The consensus of the ancient Church was that St. John the Beloved—the youngest of the Twelve, brother of St. James the Greater—wrote this Gospel, and that it was the last of the four to be composed. This consensus no longer exists. Things have receded from the frankly silly pitch of the late nineteenth century, which was more or less prepared to make the Gospel of John a work of the late second century; as far as I can tell, though it is not common among New Testament scholars, it is no longer a disgrace in Academe to accept the opinion that John is of Johannine authorship or at least based on the tradition of a “Johannine community” (why do scholars seem so much more comfortable with a book being old as long as it just isn’t by a single hand?). There is also a widespread theory that John’s author had read at least one, possibly all, of the Synoptics, and that the striking differences in material covered between them and the Fourth Gospel are at least partly a result of the author choosing for the most part to relate traditions the Synoptics had not covered.**

John is widely considered the most mystical and enigmatic of the Gospels. This has led some people to think it shows Gnostic influence—which sort of makes sense, if the only association you have with “Gnosticism” is “sounds kinda woo-woo.” If you try and match it up with any Gnostic sect’s, you know, beliefs, things get rather trickier: the fact that it lays so much emphasis on the reality of Jesus’ physical body both before and after the Resurrection, and displays no interest in involved genealogies of spiritual emanations (which are Gnostic schools’ bread and butter), makes it more plausible to my mind that John was written to nip an incipient Gnostic movement in the bud.†

I am actually rather disappointed that we don’t have a year devoted to John in the lectionary. Like Revelation, the book is rigidly structured and follows a carefully designed pattern; a great deal of its significance is lost when only selections from it are peppered here and there into other arcs. But, it is what it is, so let’s jump in.

John 2.13-25, RSV-CE

Driving of the Merchants From the Temple

(1580) painted by Ippolito Scarsellini.

The Passovera of the Jews was at hand, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. In the templeb he found those who were selling oxen and sheep and pigeons,c and the money-changers at their business. And making a whip of cords, he drove them all, with the sheep and oxen, out of the temple; and he poured out the coins of the money-changers and overturned their tables. And he told those who sold the pigeons, “Take these things away; you shall not make my Father’s house a house of trade.” His disciplesd remembered that it was written, “Zeal for thy house will consume me.” The Jews then said to him, “What signe have you to show us for doing this?”f Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple,g and in three days I will raise it up.” The Jews then said, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and will you raise it up in three days?” But he spoke of the temple of his body.h When therefore he was raised from the dead, his disciplesd remembered that he had said this; and they believed the scripturei and the word which Jesus had spoken.

Now when he was in Jerusalem at the Passover feast,a many believed in his name when they saw the signs which he did; but Jesus did not trustj himself to them, because he knewk all men and needed no one to bear witness of man; for he himself knew what was in man.

John 2.13-25, my translation

And the Jews’ Paschaa was near, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem. And in the Templeb he found people selling cattle and sheep and pigeons,c and the money-exchangers sitting there; and making a whip out of cords, he cast all the sheep and cattle out of the Temple, and poured out the money of the coin-men and overturned their tables, and said to those selling pigeons: “Take these things out from in here! Do not make this house, my Father’s house, into a marketplace!” His studentsd were reminded that it is written: “Zeal for your house has eaten me up.” Then the Jews replied and said to him: “What signe do you show us, that you are doing these things?”f Jesus replied and said to them, “Destroy this sanctuaryg and in three days I will raise it.” Then the Jews said to him, “Forty-six years this sanctuary took to be built, and you will raise it in three days?” But he said this about the sanctuary of his body.h So when he was raised from the dead, his studentsd were reminded that he said this, and believed the writi and the word that Jesus said.

While he was in Jerusalem for the feast of Pascha,a many believed in his name, beholding his signs that he did; but Jesus did not entrustj himself to them—because, that he knewk everyone, and that he had no need for someone to bear him witness about man, for he knew what was in man.

Textual Notes

a. Passover/Pascha: As in other places, we here get a translation of the Aramaic word Pascha, which Greek had simply borrowed; the Hebrew form of the term is Pesach [פֶּסַח]. (A true translation of Pascha into Greek would perhaps have been paraleipsis [παράλειψις], “a passing over, an omission.”)

b. in the temple/in the Temple: My preference for capitalizing “Temple” in reference to the Solomonic and Second Temples (which I sort of undercut in the very first textual note in my last post!) is merely that, a preference. What I actually want to highlight here is where exactly this scene took place.

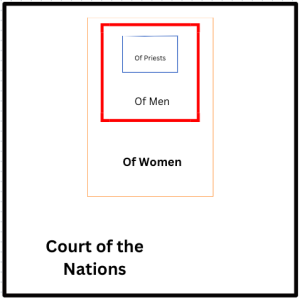

The Second Temple consisted in several smaller and smaller courts, to which fewer and fewer people were admitted. The outermost precinct was the “Court of the Nations,” where even Gentiles could enter and “God-fearers” might be able to pray. Within this was an interior wall, in which was an opening called the Beautiful Gate; beyond this lay the “Court of the Women”—only Jews could come this far in. Within that lay another gate, beyond which was the “Court of the Men,” where only males were admitted; then another gate, and the “Court of the Priests,” Levites only. The Holy Place was within this (only priests on the rota for active service that day), and on the far side of the Veil from that, the Holy of Holies, where only the high priest could go and only on Yom Kippur. It would be, very roughly, along these lines:

Image created courtesy of Canva. Not

to scale, and probably the wrong shapes

too—this is just a visualization aid.

The reason these moneychangers and animal-sellers were here at all was to furnish visitors with a one-stop shop for two important purposes (and remember, not only was the Temple operating throughout the year—sacrifices every morning and evening—it was also a site of mandatory religious pilgrimage three times a year, for Jews from as far afield as Babylon and Rome). First, they could get any Roman coins they were carrying, which were only 80% silver at the time, traded for the significantly higher-purity Tyrian shekel: they needed Tyrian shekels to pay the temple tax, the then-current tithe by which Jews in general were expected to support the Levites who ran the Temple. Second, they could purchase animals that were pre-certified as suitable for sacrifice—the appropriate species and ages, confirmed to be free of blemishes or injuries, etc. This way, pilgrims didn’t have to first find somewhere the get the right money, then risk spending hours or even days finding and purchasing an animal they could use for worship (in a strange city, no less).

That actually sounds pretty nice of them, right? What was the issue? Some commentators seize on the “den of thieves” quotation to claim that the moneychangers and livestock vendors were cheating people. Personally, I’m skeptical of that. Partly because (while we have only too much proof that human beings are capable of such behavior), it’s pretty bold to cheat the worshipers of a deity in the sacred precinct of that deity; partly because the texts give us not one but two additional, better reasons Jesus objected to this—”better,” in the sense that they retain their force even if every moneychanger and animal-seller in the building was scrupulously honest. One is expressed here: This is not a marketplace. The smells, sounds, and (we may be sure) defecations of animals should not be irrupting upon the senses here.

The other, coincidentally enough, is highlighted in Mark 11, specifically in verse 17. “Is it not written, ‘My house shall be a house of prayer for all nations’?”

A view of Mount Zion from Mount Olivet

(the church left of center is the Church

of the Dormition of the Virgin). Photo

taken by Berthold Werner in 2008.

This was taking place in the Court of the Gentiles. The one place within the Temple precinct where Gentiles come and pray to the God of Abraham, the one spot they could be included—and if any of them did seek it out, they had to contend with the bustle, noise, and smell of a Mediterranean bazaar. An atmosphere less congenial for prayer can scarcely be imagined.

c. oxen and sheep and pigeons/cattle and sheep and pigeons: The distinction between “oxen” and “cattle” here is trivial (though the word oxen is normally used only of castrated bovines in English, and no such implication applies to the Greek it translates here). The importance of the animals is that nearly all animal sacrifices prescribed in Leviticus call for one or more of them (the pigeon, or dove, rarely occurs by itself, though a number of sacrifices list it as an acceptable and affordable alternative for the poor to offer).

d. disciples/students: In principle, these words are near-synonyms in English, the main difference being that “disciple” carries more of a sense of attachment to a teacher, whereas “student” is either more neutral or more indicative of attachment to a subject. I’ve taken “student” as the more neutral of the two words, and therefore the better equivalent of the Greek mathētēs [μαθητής].‡

e. sign: Signs, primarily meaning miracles, are of particular importance in John, in a curious contrast with the Synoptics. In the other three Gospels, Jesus seems extremely pessimistic about the quality of any faith that seeks miracles, let alone relies on them. In John—which, incidentally, is the Gospel that records the fewest miracles; only nine, and that’s counting his own Resurrection—he repeatedly tells his disciples to accept his miracles as evidence of his identity; further, most of the first half of the book (1.19-12.50) proceeds according to a rhythm set by seven signs, seven miracles:

- The changing of the water into wine (ch. 2)

- The healing of the official’s son (ch. 4)

- The healing of the paralytic (ch. 5)

- The feeding of the five thousand (ch. 6)

- The walking on water (also ch. 6)

- The healing of the man born blind (ch. 9)

- The resurrection of Lazarus (ch. 11)

Strikingly (especially when compared with Mark), John, though it contains several discourses on the nature and tactics of the devil, is the only Gospel that contains no exorcisms. I genuinely don’t know what to make of this.

f. “What sign have you to show us for doing this?”/”What sign do you show us, that you are doing this?”: Contextually, it seems pretty obvious that the sense of this remark is Produce your credentials to justify this audacity; however, I have to chuckle at an alternate reading (which I believe John’s author included on purpose): You have by doing this performed a sign: tell us what it means.

g. temple/sanctuary: I’m honestly a little puzzled that the RSV doesn’t do anything to convey the distinction that’s present here in the Greek. As in the Hebrew Bible, in the New Testament, the Temple is most often referred to as the oikos [οἶκος], the “house” of God; occasionally it is called the hieros [ἱερός], the “holy [place].” Jesus uses neither of these words when he tells the onlookers to “destroy this sanctuary.” Instead, he refers to his body as the naos [ναός]. The naos of a temple in the ancient Mediterranean was its innermost chamber, the place most sacred to the god, usually housing a cultic statue representing him or her—save of course for the famously aniconic Jewish religion. It had images of its god’s attendants in the Holy of Holies, but none of the god himself. (Unless the priests and worshipers themselves counted, through a strange technicality implicit in the Jewish holy book.)

Moses and Joshua Bowing Before the Ark,

James Tissot (ca. 1900).

h. body: This is not a difference in translation, obviously, but it does happen to be a word choice with certain resonances. The term “flesh” in the famous text the Word was made flesh is sarx [σάρξ], which means “flesh” or “meat” (and is related to the term sarcophagus—literally “flesh-eater,” in case you were thinking of sleeping tonight). That is not the word used here; instead, John uses sōma [σῶμα], “body.” These terms, while not contrasted in John’s writings, are contrasted by St. Paul; he tends to use sarx for the “carnal nature” and sōma for the body in itself, the vessel capable of glorification, unlike the sarx which must ultimately be shed. Pauline terminology tended to set the tone for most Christians (and still does), and it seems likely enough that the author of John would have been familiar with it; why, if so, he specifically chose not to imitate Paul’s use of sarx is hard to say, but it’s intriguing.

Conversely, sōma already had a significant history in Greek philosophy, not unlike logos [λόγος] from the first chapter. Plato, in his dialogue recounting the death of Socrates, puns on the similarity between sōma and sēma [σῆμα], the latter meaning “tomb” or “grave.” Here again, we see John (who, even if he were a peasant living in Judæa, would have had some likelihood of at least hearing about Plato, if he knew Greek at all—and any scribe worth his salt certainly would have) seeming to deliberately reject the significance given to a word by a predecessor.

i. scripture/writ: Ancient Greek does not have a specialized word for divine revelation (there being no exact equivalent of the Bible in Greek paganism); the Tanakh is referred to simply as graphē [γραφή], “written,” or else by the name of the traditionally-ascribed author (Moses, David, Isaiah, etc). That said, the term here obviously refers to the Bible, as indicated not least by the Scriptural quotes. I therefore chose the word “writ” as a sort of compromise between literalism and idiomatic rendering.

j. trust/entrust: Here we run up against a word that just doesn’t go neatly into English: pisteuō [πιστεύω] can mean “to trust, entrust,” “to believe, have faith,” or “to keep faith, be loyal” (occasionally even covering “to keep a secret”). Obviously this is a closely-knit complex of related meanings; one-word translations cover a spectrum roughly amounting to trust–show/have faith–believe. It isn’t so much that pisteuō is hard to understand: it’s just that my preferred method of translating—one Greek word = one English word with the same nuances, if at all possible—is, in the case of this word, not possible.

k. because he knew/because, that he knew: The Greek here is a bit clunky, so I tried to convey this in the translation. This is thanks partly to John’s enthusiasm for the word autos [αὐτός]: familiar to us from the prefix auto-, this word can mean “-self” or “the same”; however, it can also serve as a generalized third-person pronoun, singular and plural, for all three genders (and since most of the masculine and neuter endings are the same, especially in the singular, it can be hard to distinguish between a he-autos and an it-autos—a point we may actually see reemerge, if we wind up in John 8 at some point).

*Specifically, it is the part of John 3 that focuses on the Son of Man being “lifted up” “as Moses lifted up the bronze serpent in the wilderness” as a miraculous cure for snakebite (Numbers 21.4-9).

**The material broadly common to all four Gospels includes:

⇒ the ministry of St. John the Baptizer, culminating in Jesus being baptized and the Holy Ghost descending on him;

⇒ some mention of the Blessed Virgin (Matthew and Luke mention her in their infancy narratives, Mark twice alludes to her briefly during the Galilean period of Jesus’ ministry, and John gives her cameos at Jesus’ first miracle and at the Crucifixion);

⇒ the calling of St. Andrew and St. Peter, as well as specific mentions of St. James the Greater, St. Philip, St. Thomas, and Judas Iscariot—if the “Beloved Disciple” is indeed St. John and Nathanael is the same person as Bartholomew (both conventional ideas), we can add SS. John and Bartholomew to that list;

⇒ Jesus’ teachings being consistently paradox-heavy and parabolic, as well as opposition to those teachings (especially about the sabbath) from the Pharisees;

⇒ a somewhat-veiled interest in the Gentiles on Jesus’ part;

⇒ the feeding of the five thousand (this is the only miracle, aside from the Resurrection itself, recorded in all four Gospels);

⇒ the triumphal entry;

⇒ the cleansing of the Temple (John relates this near the beginning of his book);

⇒ the betrayal of Judas;

⇒ the arrest (with major differences in detail);

⇒ at least one ecclesiastical trial before some of the Sanhedrin;

⇒ St. Peter’s apostasy;

⇒ Jesus being handed over to Pilate for civic trial, and Pilate’s reluctant accession to the mob’s demand for his execution;

⇒ the Crucifixion (again with major differences in detail), death, and burial; and

⇒ St. Mary Magdalene discovering that Jesus is absent from the tomb on Sunday morning.

Everything else we know about Jesus appears in a maximum of three canonical Gospels, much of it in only two; moreover, all four Gospels contain material peculiar to themselves, including Mark.

†Though its definition is a little vague, Gnosticism is not generally accepted as having begun before the early second century. Consensus dates the Gospel of John to the last decade of the first century, or the opening decade of the second, making it probably too early to have been answering any explicitly Gnostic movement, though it may well have been dealing with their immediate ideological predecessors.

‡Incidentally, this derives from the same root as the word “mathematics”: manthanō [μανθάνω], “to learn.” The names Matthew and Matthias, however, come from Hebrew and are not related to manthanō.