Quadragesima: Linguistic Tidbits

Quadragesima, the Latin for “fortieth,” is where many other languages get their words for the season we call “Lent,” such as the Spanish Cuaresma or the French Carême; the Greek Sarakosti [Σαρακοστή] (though coming of course from Greek rather than Latin roots) has the same meaning. Several cultures borrowed and adapted the Latin name: the Irish word is Carghas, Croatian calls it Korizma, and Swahili calls it Kwaresima. The English term is one of a handful of outlier names for Lent, mostly from places that were Christianized later than the Mediterranean. Many of them call it “the fast” or “fasting time,” such as Czech’s Postní Doba or German’s Fastenzeit. One of my favorites is Maltese, which was Christianized pretty early but is also the only Semitic language native to Europe; its name for it is Randan, borrowed from the Muslim practice of Ramadan. (Interestingly, Christians who speak Arabic don’t use the name Randan, or one like it either: their name for Lent is al-Šawm al-Kabīr [الصوم الكبير], “the Great Fast.”)

The English name Lent is unusual even among the outliers, though related terms used to be used by speakers of Dutch and German. It comes from lencten, an Anglo-Saxon word meaning “spring [season]” or “springtime”—itself related, indirectly, to the word “long,” because the days become longer over spring. I’m not sure why English opted for a seasonal name; the only reason I could think of is that the differences between seasons are more stark in the British Isles than they are in the Mediterranean. (I believe I read somewhere or other that the Ember days—four periods of fasting in Advent, Lent, Whitsuntide, and September—which roughly mark the four meteorological seasons, had more cultural importance in England than elsewhere, but unluckily I can’t recall even the source.)

Sun and Moon, illustration from

the Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493

Now then! The first Sunday in Lent is traditionally devoted to the temptation of Christ in the wilderness and the Transfiguration, which is recounted in all three of the Synoptics. Let’s jump in.

Mark 1.12-15, RSV-CE

The Spirita immediately droveb him out into the wilderness.c And he was in the wilderness forty days, temptedd by Satan; and he was with the wild beasts; and the angelse ministered tof him.

Now after John was arrested,g Jesus came into Galilee,h preachingi the gospelj of God, and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdomk of God is at hand; repent,l and believe in the gospel.”

Mark 1.12-15, my translation

And right away, the Spirita castb him into the desert.c And he was in the desert forty days, being testedd by Satan, and with wild animals; and the messengerse servedf him.

And after John was handed over,g Jesus came into the Galilee,h proclaimingi the good newsj of God and saying that “The time is fulfilled, and the kingshipk of God has come near; change your mindsl and believe in the good news.”

Textual Notes

a. the Spirit: The preceding context—Christ’s baptism in Mark 1.11—does suggest that the spirit in question here is “the Spirit,” i.e. the Holy Spirit, who just descended upon him. However, it is also possible to translate the text here “the spirit” or “his spirit”; the reason why is worth a little attention, due to its implications for the rest of the Bible.

Scripts at this time did not have what we today call the distinction between upper and lower case. Different varieties of writing did, including the different letter-shapes now often covered by case, like E vs. e or H vs. h. This distinction is referred to technically as the difference between majuscule and minuscule writing: majuscule letters are all strictly confined between an upper and lower line (no ascenders or descenders), are generally older, and tend to go on showing up in inscriptions thanks to their simpler, more geometric shapes:

LEGETE IN LIBRO HÆC VERBA, AMICI.

The sentence “Read these words

in the book, friends” in majuscule lettering.

Minuscule hands have some portion of each letter in between two lines, but allows both ascenders and descenders to an upper and lower boundary, and are generally developed out of majuscules.

legete in libro hæc verba, amici.

The same sentence

as above, in minuscule.

Further, the relationship between majuscule and minuscule hands was quite different then—a little like the modern relationship between print script and cursive (and minuscule did essentially evolve as a form of cursive). To mix the two would have struck contemporary writers and readers as absurd; as a result, there was no such thing as capitalization when the Gospel of Mark was composed. All capital letters in the New Testament are translators’ decisions.

The real forerunner of capitalization is rubrication: the use of red ink, to indicate a heading, a particularly important sentence, etc. (coming from the Latin word ruber, “red”). Rubrication may have been quite ancient—I’ve seen a claim (unsourced) that it went back to pre-Roman Egypt—but, as far as I can tell, it did not become commonplace until the Medieval period, and there is no guarantee rubrications were universally consistent or anything like it. Red ink may not have been equally available to every scribe; it’s also possible that what to rubricate might have been viewed as a matter of the needs or tastes of the person the manuscript was being produced for, rather than an inherent property of the text.

b. drove/cast: The verb used here, ekballō [ἐκβάλλω], literally means “to out-throw,” or more idiomatically “to expel, throw out.” Strikingly, this is the verb most often used to describe what Jesus does to demons when ejecting them in an exorcism, which is why I opted for “cast.”

c. wilderness/desert: The Greek here is erēmos [ἔρημος]. It’s possible that the RSV uses “wilderness” here on the grounds that while in the environs of Judæa pretty much any erēmos will be a desert, the word can refer to other varieties of unsettled land. I’ve preferred “desert” on the grounds that it evokes precisely the salient quality of an erēmos, namely its remoteness: it is “lonely place,” a place that has been deserted.

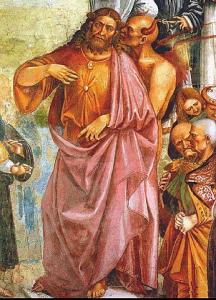

Selection from The Preaching

of the Antichrist by Luca Signorelli,

ca. 1500-1504.

d. tempted/tested: The Greek can mean either “tempted” or “tested.” However, we’re oddly apt to forget the fact that the English word to test has similar double meanings: it can refer to a test of knowledge, or one of character; it can be neutral, or it can be hostile. I therefore consider “test” a far better translation.

The fact that Mark elects not to detail the three stages or aspects of the temptation, unlike Matthew and Luke, is interesting. On the hypothesis that Mark was written first and the other two later, one possibility would be that the authors of Matthew and Luke embroidered their accounts; another would be that Mark wrote his version as a rapid summary, only attempting to get the main outline down, and a more settled recollection informed the other two Synoptics. Alternatively, on the traditional theory that Matthew was first and Mark is Peter’s memoirs more strictly, perhaps he includes the temptation because the story would be incomplete without it, but goes into little detail because he did not witness it.

e. angels/messengers: The word angelos [ἄγγελος] means “messenger,” a direct translation of the Hebrew mal’akh [מַלְאָךְ], one of the normal terms for these beings in the Tanakh. I usually prefer to translate this word literally, especially since (though I could be wrong about this) I think a reader familiar with the New Testament will easily be able to identify when angeloi means “messengers” and when it means “the Messengers,” so to speak.

f. ministered to/served: In the past, like the Greek diakoneō [διακονέω], the English “to minister” was much nearer in meaning to the word “to serve” (which is why public servants are also called state ministers). Today, associations with administration (and maybe other forces too) have almost completely leached the original meaning out of “minister,” making “serve” a more accurate translation.

g. arrested/handed over: This translates an important term in the New Testament, paradidōmi [παραδίδωμι]. By “important,” I do not mean that it is a technical term—I mean it has a wide variety of meanings. (As a matter of fact, paradidōmi stands behind the words usually translated both “tradition” and “to betray,” a fact that, strange to say, I’ve almost never seen Protestants take advantage of for cheap-shot jokes; c’mon, guys, it’s right there.) “Handed over” seemed to me open-ended enough to hint at something of the breadth of the actual word used, while still being particular enough to indicate that the handover in question has the nature of an arrest.

h. Galilee/the Galilee: I don’t recollect when it was exactly, but in one of my prior posts, I related that the name Galilee comes from a word meaning “wheel,” and that for this reason it is occasionally called “the Galilee”: “the,” because of the meaning, but “Galilee,” because the language being translated here is Greek—I prefer to leave Aramaic terms (or those in any other non-Greek language) roughly as they are.*

i. preaching/proclaiming: “Preaching” is, as so often, not inaccurate here but a little misleading. The verb used comes from kērüx [κῆρυξ], which means not preacher but “herald.” This is yet another instance of the New Testament using language we would normally associate with political rather than religious figures in its Classical context, but for which the conventional translations have become almost exclusively political, resulting in a very warped perception of the text.

j. gospel/good news: Only in looking up what I’d previously said about this specific word did I remember that I have translated and annotated verses 14-15 before (as part of a differently-selected passage). Sigh. Anyway, I won’t reproduce everything I’ve said before about “gospel” vs. “good news”; I will reiterate that, besides literally meaning good news, an euangelion [εὐαγγέλιον] was a specifically official, typically an imperial, announcement—a piece of news that a herald, yes, or some kind of emissary (a.k.a. an apostolos [ἀπόστολος]), might be sent out to publish abroad.

k. kingdom/kingship: This, too, I’ve written about before! However, because “the kingdom of heaven” or “the kingdom of God” is so important in the Gospels, it’ll be worth our while to review.

A map of Palestine under Herod Agrippa I;

the territory he ruled from 37-44 is shown

in pink (orange indicates predominantly

Gentile areas, which would have been mostly

a Græco-Syrian blend).

First, it’s rather striking that Mark uses the phrase “kingdom of God” in contrast to Matthew’s “kingdom of heaven.” There is, of course, a stern prohibition against taking the Lord’s name “in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.” (This likely indicates swearing false oaths or making false or rash vows.) For this reason, as time went on, to pronounce the divine name at all became increasingly taboo in Jewish culture; by Jesus’ time, it was only meant to be pronounced by the high priest, in the Holy of Holies, on Yom Kippur. It’s thought that Matthew—which, whether it was the first Gospel written (as I’m inclined to think) or not, was certainly addressed to a Judaic milieu—uses the phrase kingdom of heaven rather than kingdom of God out of sensitivity to the reverence surrounding the Name, a reverence he probably shared. The fact that Mark does not do this is thus attention-grabbing. This may reflect a desire to maintain Jesus’ words as exactly as he could recall; this would fit with the fact that Mark contains a larger share of Aramaic than the other Gospels, and at times seems to have the best and most detailed chronology (notably in ch. 11).

Second, on the kingdom/kingship distinction I’ve drawn. In English, I think the territorial sense of the word “kingdom” tends to be foremost in our minds, as distinct from the office of kingship. The same was not necessarily true of the Greek word basileia [βασιλεία]; its center of gravity was more in the office than the domain. Thus, a phrase like “the kingdom of heaven” somewhat inclines us to imagine the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven—primarily a place. I can’t speak for whatever the Aramaic was, but the Greek sends a different message, one better understood as a state of affairs than as a place. The reign of God, the rule of God, these phrases are more in line with the drift of the Biblical text we possess.

La Jérusalem Céleste, a 14th-century

tapestry from a castle in the city of

Angers in northwestern France. Image used

under a BY CC-SA 4.0 license (source).

l. repent/change your minds: The Greek here is metanoeō [μετανοέω], itself derived from the noun nous [νοῦς], “mind.”** I bring this up because, while the ancient world used a lot of the same words to describe the inner aspects of the self (“mind,” “gut,” “heart,” etc.), a given organ often “meant” something quite different in classical cultures. (Indeed, some of the then-standard metaphor-bearing organs have dropped out of popular figures of speech more or less completely: the liver, once the seat of the irrational appetites in general, is an excellent example, and the spleen and kidneys now hang on exclusively in rare, literary expressions like vent one’s spleen or of that kidney—indicating “to express irritation or anger caused by anxiety” and “of that temperament, character, or quality,” respectively.) These words can accordingly give a misleading impression today, with post-Enlightenment, post-Romantic ideas of what brains and heart mean, and of how they are and ought to be related to each other.

In the ancient world as today, the heart (kardia [καρδία] in Greek, cor in Latin)† was more or less universally considered the primary seat of emotion, from Baghdad to Britain. However, the Greeks—for the most part—followed peoples like the Egyptians in also considering it the seat of rationality, and to some extent the Romans did as well; if a Roman called a man he knew cordatus or “[good-]hearted,” they meant not that he was conspicuously kind, cheerful, easygoing, or things along those lines, but rather that he was prudent or had good sense. Mind and heart were, accordingly, near-synonyms, and “have a change of heart” would be nearly as good as “change your mind,” if we’re going to replace the term repent for this translation (because, and say it with me, “repent” now has more or less exclusively religious connotations).

Why, then, have I opted after all for “mind”? Well, partly because that is what nous means; nous, not kardia, is the root of the verb we’re dealing with. And partly also because, while the heart was a far more rational organ to the ancients, the mind was still thought of as the “data-gathering center.” Like many verbs of knowledge, noeō [νοέω], the basis of metanoeō, had connotations of perception as well as thought; it would be very free, but not exactly inaccurate, to render the command of verse 15 as “Get a fresh perspective.”

*If I went full Tolkien about it, trying to find the cultural-and-linguistic equivalent to a modern English speaker of Aramaic to a first-century Greek speaker, … well, there wouldn’t be one really, because our social systems are too radically different. If we absolutely insisted, the languages we’d need to do justice to are not only Greek and Aramaic, but also Hebrew, the sacred language of Judaism. There is, therefore, a case to be made that the best equivalent of New Testament Aramaic in passages like this is—wait for it—Modern Greek, as a close but distinct relative of Biblical Greek, which would in this analogy equate to Hebrew. (A medieval or modern Romance language as the stand-in for Aramaic, and Latin for Hebrew, would be the next-most convincing choice; I place these second rather than first because English has been far more influenced by both Latin itself and the Romance languages than Greek ever was by the Semitic ones, which would result in a false impression of the real linguistic situation.)

**This forms the basis of the Greek name for the sacrament of penance to this day, metanoia [μετάνοια].

†A little unusually, the English heart is actually, if distantly, related in this case to the Latin and the Greek! All three descend from the proto-Indo-European word for “heart,” which is thought to have been *ḱēr or *ḱērd. (The letter h often represents a sound that, in Anglo-Saxon and further back, was much stronger than in today’s English—more like the modern Spanish j or German ch; this is why words like hound and hundred are our native parallels of Latin’s canis and centum.) This word also formed the basis of a verb that, in Latin, took the form crēdere, “to believe,” from which we get “creed”; to proto-Indo-Europeans, it meant “where you put your heart.”