A Celebrity Exorcist

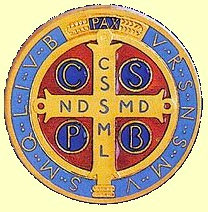

The back of a jubilee casting of the St.

Benedict medal. The letters, first those

of the cross and then of the outer ring,

stand for the vade retro.1

In the interest of time, I will be skipping the one-week dip into Matthew we made on 1st September, and am discussing the Gospel texts both from the 8th and next Sunday in this post. Part of the reason for my delay was that I was toying with doing a post that would have been more in line with my old material, a response to something I found on social media that rather disquieted me. I decided to write that post, but to combine it with my in-the-works post addressing Mark 8.27-35, the Gospel for this coming Sunday. Mark’s version of this event is briefer and gives less detail than Matthew’s, an interesting difference in its own right; more on that later. (If you’re only here for textual commentary, skip down past the picture of the papal keys and tiara.) Then of course the relatively-unconnected initial bit turned out to be longer than I planned on—so I’m publishing the first half of this post tonight, before I can be bamboozled yet again into believing my lies that it won’t take long to do the rest!

If you haven’t heard before of Fr. Chad Ripperger, he’s a traditionalist Catholic priest, a member of the FSSP, currently serving the Archdiocese of Denver (formerly other dioceses in the heartland, e.g. Lincoln and Tulsa), and a celebrity exorcist. I recently saw on Twitter that he had been saying something or other—I’m not sure when, this might be old news—about “Satan’s five generals” (sure) that are supposedly in charge of ruining America (where else would they go). Now, if, backing up just a bit there, the phrase “celebrity exorcist” struck you as one of the most “heck no at all” combinations of words in the English language: you are severely correct! Let’s discuss.

The Discernment of Spirits

To be clear, as far as I know, it is not strictly forbidden for exorcists to identify themselves to the public. A few have, like Fr. Malachi Martin, author of the lurid volume Hostage to the Devil.2 However, most don’t; it is contrary to the Church’s cultural norms, so to speak, and these particular norms exist for very good reasons. For one thing, exorcism is extremely private. What could be more intimately personal, or in all probability more traumatic, than having your very body inhabited by a hostile intelligence that isn’t even human? When exorcists tolerate or even court publicity, questions about exorcism and demons are all but invited. That’s not great, due to the privacy issue, but also for another reason: namely, that, while there are specific circumstances under which spiritual warfare becomes unusually explicit and direct, the best way of confronting demons is usually—not to.

Like, look how badly this is going

This is partly because of how demons work, so to speak. As is well-known, they can masquerade as angels of light; since angelic intellects are of a different kind than ours, and a kind that (we’re given to understand) is generally more powerful, demons are able to practice this kind of deceit even with such decayed relicts of mind as they still possess. However, though their lies can become quite subtle—as in Eliot’s brilliant line, “The last temptation is the greatest treason: to do the right deed for the wrong reason”—the truth is, they don’t usually need much real subtlety to fool us, because most of us are rather lazy creatures who don’t like thinking any harder than we have to, or indeed as hard as we have to.

Charles Williams, describing Catholic attitudes to witchcraft in the Early Middle Ages,3 wrote that “the Church seems to have felt that to believe anyone could [cast spells], to believe that one could oneself do it, and to do it were three degrees of preoccupation with the same evil.” While the Early Middle Ages lasted, the Church’s solution was to discourage belief in witchcraft, as well as attempts at it4; and a very sensible solution it was. In the same vein, it’s just not generally good advice to focus on demons. They feed on attention, chatter, anxiety. They’re not even interesting; not really. Once you break through the carapace of lies they hide behind—there’s nothing inside. That’s how demons work. Accordingly, when dealing with exorcists, self-identified ex-cultists, and the like, I recommend examining what they say or write with the following test in mind: Is this person drawing attention to devils, particularly in the ways they feed on—fear and curiosity?

Pay No Attention to the Priest Behind the Curtain

So, when Fr. Ripperger not only gains notoriety as an exorcist (a sufficiently bad and distasteful phenomenon in itself), but seems to be professing detailed knowledge of the infernal hierarchy, knowledge not vouchsafed to the Church at large … well, only one other source for that knowledge springs to mind. I for one would be exceedingly frightened and worried by the fact that this man apparently has the faculties of a homilist and confessor5 in the Archdiocese of Denver! That is, I’d be frightened and worried by it, if I could bring myself to believe for an instant that Fr. Ripperger really has access to mystical information of that kind. As it turns out, I can’t bring myself to believe that for an instant; which was rather a relief.

However, it doesn’t follow that there is nothing to be concerned about. Look at the question from this angle. It’s obviously not flattering to say about anybody that they’re careless about the truth; but what does a remark like that, if correct, say about an exorcist of all people?

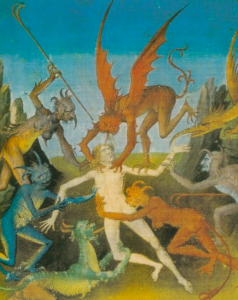

An illumination of St. Michael and the dragon

fighting, thought to date to the 1170s, now

housed in the Getty Museum.

Trent Horn, a Catholic Answers apologist (whom I can’t truthfully claim to like much, due partly to my mere constitutional impatience with apologists), spoke extremely good sense about the whole business five years ago, in an episode of his podcast, Counsel of Trent.6 The episode features Horn pinpointing quite a number of factually incorrect claims (several of them about faith and morals) made by Fr. Ripperger in the course of an interview. In one clip he played, Fr. Ripperger related a story of an exorcism in which he was personally involved (though he was obliged to hand the case over to another exorcist because he was moving? something seemed odd about this, but, beside the point). The exorcism in question featured a set of demons who wrote the Harry Potter books, because of course it did. Horn pauses the interview and remarks:

I know people in deliverance ministries, by the way … they are not allowed to talk about what they hear or see in exorcisms. They’re not allowed to share it with anyone, because that’s what a demon wants. A demon wants attention. … I don’t know why Father Ripperger is sharing that. Two, why should I believe these demons at all? They are sent by the father of lies. Why believe anything they say?

That is indeed the question. Worse, this is not our first rodeo, or even our first rodeo in the last ten years. The inability of many trads to raise this question strikes me as—to put the matter in disgusting and offensive terms (where topics like demonic possession belong)—the spiritual equivalent of “asking for it.”

A “carpet page” from the Book of Lindisfarne.

This has nothing in particular to do with

the current subject of this post, I just wanted

a palate cleanser.

The Bottom Line

When the quoted podcast aired, five years back, Trent Horn was able to find it in his heart to treat Fr. Ripperger in generous, even complimentary terms, while still carefully identifying the easily provable falsehoods that positively poured from this priest’s mouth. I don’t know whether Horn has rethought his view of Fr. Ripperger since. Either way, I am not willing to invoke that kindness upon this kind of behavior—not for a priest, not for someone whose literal day job is teaching the faithful what is meant by commandments like “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor” and “Thou shalt not take the Name of the Lord thy God in vain.”

Do not trust Fr. Ripperger. Not about demons, or frankly anything, if he’s careless about truth and fact with a matter he professes to take so seriously. Not only is he repeatedly, publicly failing the test of Is this person drawing attention to devils, particularly in the ways they feed on (fear and curiosity)? He fails two tests that are even more basic, and about as subtle as painting oneself purple and dancing naked on top of a harpsichord7: first, the moral test of Can this person be relied upon to tell the truth?; and second, the intellectual test of Does this person trust sources of information that are infamous for being deceitful?

However. It does bear saying that people, and indeed priests, have done worse and sillier things than make up lies for attention. We’ll be meeting one such priest in our second text.

Mark 7.31-37, RSV-CE

Then he returned from the region of Tyre, and went through Sidon to the Sea of Galilee, through the region of the Decapolis.a And they brought to him a man who was deaf and had an impediment in his speechb; and they besought him to lay his hand upon him. And taking him aside from the multitude privately, he put his fingers into his ears, and he spat and touched his tonguec; and looking up to heaven, he sighed, and said to him, “Ephphatha,”d that is, “Be opened.” And his ears were opened, his tongue was released, and he spoke plainly. And he charged them to tell no one; but the more he charged them, the more zealously they proclaimed it. And they were astonished beyond measure, saying, “He has done all things well; he even makes the deaf hear and the dumb speak.”

Mark 7.31-37, my translation

And he came back again from the mountains of Tyre, coming via Sidon to the Sea of the Galilee, up amid the mountains of Ten Boroughs.a And they bring him a dumb deaf-mute,b and appeal to him that he lay hands on him.

Taking him aside from the crowd by himself, he thrust his fingers into his ears, and spat and touched his tongue,c and looking up to heaven he groaned, and told him: “Effatha“d (i.e., “Be opened up”); and his hearing was opened, and the bond on his tongue was loosened and he spoke rightly; and he ordered them to tell no one; yet as much as he ordered them, they preached it so much the more instead. And so much the more overawed on top of that, they were saying, “He has done everything well—he makes the deaf hear and the speechless speak!”

Textual Notes

Egyptian-era columns submerged off the coast

of modern Tyre. Photo by Roman Deckert,

used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license (source).

a. Decapolis/Ten Boroughs: This area has come up once or twice before; it lay principally in what’s now northwestern Jordan and the southernmost parts of Syria, and at the time was inhabited mainly by Gentiles of blended Græco-Syrian ancestry. Strictly speaking, Δεκάπολις [Dekapolis] simply means “ten-cities,” smushed together into a single word and treated as a regional name. Perhaps just because I’ve been reading about early medieval England recently (during which there was a sort of province known as “the Five Boroughs“), an expression like “Ten Boroughs” struck me as a form that Δεκάπολις might naturally take in translation.

b. deaf and had an impediment in his speech/dumb deaf-mute: The Greek words here are κωφός [kōfos] and μογιλάλος [mogilalos]. Κωφός covered the disability-to-insult range of meanings the word “dumb” can carry in English, but could also indicate deafness; μογιλάλος, literally “talks with difficulty,” seems to have been a generic term for those with speech impediments. I therefore aimed to render the two words with something slightly redundant but not meaninglessly so.

c. he put his fingers into his ears, and he spat and touched his tongue/he thrust his fingers, etc.: To my mind at least, this part of the passage is quite striking—allowing for differences of period and cultural habit in such things, it sounds a little bit like a medical exam.

I wasn’t able to confirm what, if any, folk beliefs about spitting existed in first-century Palestine. The notion of spitting to ward off the evil eye is a very ancient and widespread superstition, but I’m not sure what this healing would have had to do with the evil eye; one source I found, an article on the encyclopedic site Sefaria, does confirm that this idea about spitting has its place in Jewish culture, but it also relates that the idea may come from this story!

d. Ephphatha/Effatha: This is one of the many instances of Aramaic words in Mark. I think the original form would have been אֶתְפָתַח [‘eth’phâthaḥ] (couldn’t find a version with the vowel pointing); however, Galileans softened the pronunciation slightly, blending the first th-sound into the f-sound that followed it and dropping the final ḥ. (The letter ח [cheth], which I’ve transcribed as ḥ, is what’s called a pharyngeal consonant, a very guttural sound, related to the sound of the letter “q” in Arabic.) The upshot of the Galilean accent, then, would be that Mark’s transcription is very precisely correct. Grammatically, as far as I can make out, it’s a fairly simple verb form, just the passive imperative of “to open.”

Footnotes

1The words of the prayer are, in the Latin the initials on the medal represent:

Crux sacra sit mihi lux:

Non draco sit mihi dux.

Vade retro Satana:

Numquam suade mihi vana.

Sunt mala quæ libas:

Ipse venena bibas.

In English, this can be rendered: “Holy Cross, be thou my light; may the dragon never rule me. Get thee behind me, Satan; tempt me not with worthless things. You pour out only evils; drink the poisons yourself.”

2To those of my readers who know something about Fr. Martin’s slightly dubious post-priesthood career as an author, this is what we in the writing biz call “foreshadowing.”

3To be clear, this is well before the institution of the Inquisitions (the two leading Inquisitions being the Spanish and the Roman, the latter operating in the Papal States). What Williams is talking about in the quoted passage dates to around the reign of Charlemagne, centuries before. Also, for the purposes of this post, I am using the term “witchcraft” in the old-fashioned sense, in which it is a form of religious devotion to a being that professes to be Satan, and is believed by them to be Satan, as understood by Christians. (This is not the same thing as either modern Satanism or the various pagan/neo-pagan groups now active.)

4It’s not widely known, and the popular picture of the period misleads us, but the Early and High Middle Ages were a period in which witchcraft was believed, especially by prominent and educated clergy, to be powerless. The “witches’ sabbat” in particular was denounced as a diabolical illusion in the Canon Episcopi (an anonymous but influential text, first attested in the tenth century). It may sound contradictory to say “Witchcraft isn’t real, so cut it out with the witchcraft,” but there’s more sense in this than may appear at first glance; the sorts of things that the grimoires claimed would earn the attention of the Pit tended to be harmful, or at least dangerous, quite independently of whether or not they worked. And the Church, to do her justice, has on the whole not been hot on the idea of people devoting themselves to Satan even by ineffective means.

5For anyone not familiar, “confessor” in this context—a little counter-intuitively—denotes someone authorized to hear confessions as part of the sacrament of penance. The term for a person making such a confession is the “penitent.”

6A title of which two things must be said: 1) ew, and 2) how dare he come up with a pun that good before I did.

7This way of putting it might strike some readers as oddly convoluted. (I know you already know all about it; you pick up on these things quickly, I’ve always liked that about you.) Its origins lie in the Blackadder line, “You wouldn’t know a subtle plan if it painted itself purple and danced naked on top of a harpsichord, singing ‘Subtle plans are here again.'”