An Episode of the Best Show

Several years ago, a cartoon show aired on the Disney Channel.1 It was titled Gravity Falls, and still is, and it’s some of the best television in all of the television.

In the rural Oregon town of Gravity Falls, twelve-year-old twins Dipper and Mabel Pines are summering with their deeply ornery Great Uncle (“Grunkle”) Stan, owner of a tourist trap called the Mystery Shack. While doing chores, Dipper discovers an anonymous journal: the cover just says “3,” inside a hand outline with six fingers. Dipper and Mabel, when she’s not being distracted by heartthrob boys (and sometimes when she is), rapidly discover Gravity Falls is seething with paranormal activity, and the author of Journal #3 documented a lot of it before his disappearance. With help from the Mystery Shack’s teenage cashier Wendy and chubby handyman Soos—and even, spoilers, the reluctant cooperation of Grunkle Stan—the Pines twins delve into Gravity Falls’ secrets too … only for us learn that all along, two characters had a far clearer idea of what’s going on than they admitted, and the weirdness of this sleepy Cascadian town may prove deadly.

This post isn’t about any of that plot stuff, but I needed to talk about it for the vibe of this post and, more importantly, because Gravity Falls is some of the best television in all of the television). In one episode, Grunkle Stan takes the kids on a tour of other local tourist traps, in order to sabotage them (and thus benefit the Mystery Shack indirectly). One of the sites they visit is Upside-Down Town, “the nausea capital of the state”:

This is clearly fair use, Disney, get off my dick

That red-lined cylinder at the top of the stairs there is where guests at Upside-Down Town are given the (amazingly powerful!) velcro shoes they need to traverse the place, and make the transition to reach the front door at the top of the house. (It may be no surprise to those who cherished the Homestar Runner legendarium2 that Matt Chapman of the Brothers Chaps was among the show’s writers and voice actors.) The specifics of this location are also not what this post is about; again, vibe. I want you to have the whimsical idea of Upside-Down Town in your mind as we begin.

The Epistle for the Saturday

of the Thirteenth Week After Trinity

That was this past Saturday. (It was also the memorial of St. Aidan of Lindisfarne, but memorials don’t normally have distinctive Scripture readings.) Daily Masses typically have two readings, rather than the three of Sundays; the first reading occasionally comes from the Old Testament, but more typically the New, as on this occasion.

I Corinthians 1.26-31, RSV-CE

For consider your call, brethren; not many of you were wisea according to worldly standards,b not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth; but God chose what is foolish in the world to shamec the wise,a God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong, God chose what is lowd and despised in the world, even things that are not, to bring to nothing things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God. He is the source of your life in Christ Jesus,e whom God made our wisdom,a, f our righteousness and sanctification and redemption; therefore, as it is written, “Let him who boasts, boast of the Lord.”

I Corinthians 1.26-31, my translation

Look at your calling, brothers, that not many of you are intelligenta according to the flesh,b not many are able men, not many are high-born; but it is the world’s stupidities God has selected, to shamec its intelligentsia,a and it is the world’s weaknesses God has selected to shame its strength, and the world’s low-bornd and devalued things, God has selected—the things that are nothing—in order to abolish the “somethings,” so that no flesh will brag to the face of God. From him, you are in Jesus the Anointed,e who was made intelligencea, f for us by God, yes, and justice and sanctity and ransom, so that, as it is written: “If you’re going to brag, brag about the Lord.”

Textual Notes

Interior of the central dome of Hagia Sophia

(photo by A. Savin—FAL license). Note the

pendentives displaying angels, which were

concealed while the building was a mosque.

a. wise … wise … wisdom/intelligent … intelligentsia … intelligence: The Greek here, and throughout the opening couple chapters of I Corinthians, is the famous word σοφός [sofos] (“wise, shrewd, clever”), and here and there its derivates, like the noun σοφία [sofia] (“wisdom”) or the verb σοφίζω [sofizō] (“to instruct”). Most of the individual elements of this word-complex go into English fairly easily. However, in the aggregate, they resist my preferred method of translating related sets of words in the rendered language into related sets of words in the target language—as exemplified in the first sentence of this note, actually: to my knowledge, there’s no verb that’s related to wise and wisdom as they are related to each other,3 so I had to fall back on instruct.

It is also a little tricky to convey a proper sense of this concept as it existed in ancient Greek culture when writing in English. We know wisdom is one of the classical four cardinal virtues, but we don’t necessarily perceive the differences between the feel of the English wisdom (a good Anglo-Saxon piece of vocabulary, descending little-changed from wīsdōm, “good judgment”) and the feel of the Greek σοφία [sofia]—a word that, in origin, meant something like “clever workmanship” or “deftness,” without the mystical aura it would later acquire.

This is at least partly due to certain changes in technology, society, and education that have taken place in the, well, couple thousand years since the New Testament was written! Let’s focus on literacy, which gives us a kind of snapshot of the whole.

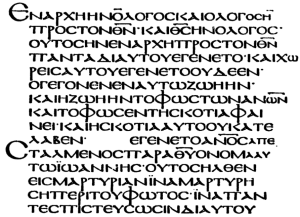

Beginning of the Gospel of John from Carl

Gottfried Woide’s facsimile of the Codex

Alexandrinus.1 Photo’d 2009, used under a CC

BY-SA 3.0 license (source—author unnamed).

Imagine we’re in the Mediterranean, doing a classical antiquity. There is a scribal class in our society, and it’s rather unusual in not being (like other classes) primarily hereditary; its members may be anything from slaves and freedmen to the lower ranks of the aristocracy. Entry into this class is obtained by the ability not only to read (which is a little more widespread, especially among the wealthy), but to write, because this is a skill—almost, a trade—that comes with substantial training in a great deal else. Many people can’t read, and most can’t write, because fish and sheep and barley aren’t going to catch, shear, and harvest themselves, even if you didn’t need to worry about thieves and lions and powdery mildew. Accordingly, while it’s not a compliment to call someone illiterate, the insult is not a harsh one; at worst, it dismisses its target as “typical,” not as atypically bad.

Now imagine we’re catapulted into the present (and that we survive, physics be damned). Not only agricultural work, but a massive amount of artisans’ work (notably in textiles), is done with so few people, the ancients would hesitate to call it even a skeleton crew, except in the sense that they’d expect our whole society to be skeletons in short order due to starvation and cold—the difference being our machines. Even in a society as massively unequal and unjust as ours, there is still so much more time at our disposal that nearly everyone is taught to read and write, from childhood, and illiteracy borders on complete powerlessness. Today, when used as an insult, “illiterate” is pretty severe.

In sum: given how intimately brains, scholarship, and the ability to read and write were tied together in antiquity (and the Middle Ages), the spread of literacy to all classes of modern society has radically reshaped the way we understand the virtue of wisdom. It’s therefore oddly tricky to satisfyingly translate some words that are not, in theory, hard to grasp.

I detour to make this point, because Paul’s opening line in our text (especially since I ultimately went with the rendering “intelligence”) could otherwise come across as a shockingly cruel, or maybe an ingenuously tactless, statement! “Not many of you are intelligent according to the flesh”—like wow, Paul, in this house we offer folk a pot of coffee before telling them they’re idiots but okay. But that’s really not what’s going on here; something with a more academic ring to it might have been closer in this text. (This is the reason why, e.g., “shrewd” did not, as it otherwise might have, win out over “intelligent” to translate σοφός in my eyes; it’s also why I stretched “intelligent” into “intelligentsia” in its second occurence.) Paul’s point is not that the Corinthian Church is “no MENSA chapter” in the sarcastic sense, but that it is literally not a MENSA chapter: i.e., neither education nor brains are what structure the Church; Jesus structures the Church.

b. by worldly standards/according to the flesh: With this idiom, you just kind of have to choose whether you’re going to translate the words or the sense. I went with words, partly because of my preference for literalism, but also because I believe the expression “according to the flesh” may have been a specifically Christian figure of speech.

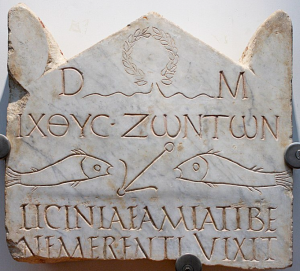

Third-cent. funerary stele decorated

with two fish and an anchor, possibly

indicating a Christian burial.

c. shame: After going through a couple revisions, I realized that what I want to say in connection with this isn’t textual commentary at all, so consider this note an optional extra! (I’d delete it, but not doing so for the sake of the footnotes is my birthday gift to me.)

The word καταισχύνω [kataischünō] is a form of the verb αἰσχύνω [aischünō] (“to shame, disgrace”) with an intensifying prefix on the front.4 I’d normally look for some other word than “shame” in these circumstances, ideally something with a prefix, to maintain the Greek-to-English parallelism that I like; “disgrace” would normally be a good example. However, I want to save “disgrace,” because if I find a verb of roughly that meaning that’s based on the verb χαίρω [chairō] (from which the Greek word for “grace” is derived), I’ll be kicking myself that I used it on a different verb. Then “humiliate” struck me as a satisfying synonym, but, as I looked at the etymologies a bit more, I wanted to save up “humiliate” too.5 I’ve therefore, although disgruntled, stuck with “shame.”

An illuminated capital from a French

manuscript, depicting the three Medieval

classes: clergy (who mostly absorbed the

ancient scribal class), nobles, and peasants.

d. low/low-born: A literal translation here (the word is ἀγενῆ [agenē]) would be “unborn,” but, both because of the pro-life controversy and due to a few other patterns of English usage, this would create a highly misleading impression of the text! A closer parallel could be found in the antiquated insult of calling someone “a man of no family,” i.e. not of a respectable or prosperous family.

e. He is the source of your life in Christ Jesus/From him, you are in Jesus the Anointed: I don’t know where the RSV is getting “life” here—I assume it’s a liberty of translation taken for the sake of a sentence they thought sounded more natural in English (unless they’re viewing ἐστε [este] “you are” as being used in a “you live” sense, which isn’t impossible). My “from him” could have been replaced with “by him,” or more loosely “by his choice.”

f. wisdom/intelligence: I hadn’t thought about this before this year, or maybe before the last month or so. Jesus was a rabbi, one of the most intensely intellectually demanding professions there is, among a people whose national language is the argument (and if you don’t believe me, read just this one chapter from the Mishnah6: if it makes perfect sense to you, congratulations, you’ve probably got as much brains as a rabbi; go argue with one of them, why don’t you). The man had brains. And yet, if you read all four Gospels, while you’ll find plenty of moral counsel, you’ll find practically nothing about the value of education, culture, books, learning—he doesn’t even urge people to study Torah, or at least not frequently and unambiguously; the occasions in those two linked passages are the only ones that sprang to mind. Similarly, one of his most famous disciples, Paul of Tarsus, is universally recognized as among the most educated men of the ancient Mediterranean; and to Corinth—a city at most a few days’ journey from Athens and its colleges (“the Boston of Greece,” as Larry Gonick called it)—he writes, just a few verses on from our text: “I have resolved to know nothing but Jesus Christ and him crucified.”

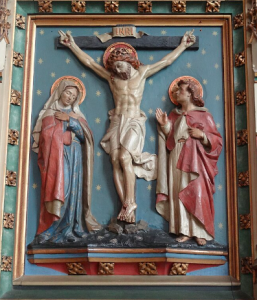

Crucifix relief at the pulpit of Canterbury

Cathedral. Photo by Jonathan Cardy,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

(source).

I’ve said little about it in the textual notes, because the niceties of translation for the passage don’t bring this meaning to the fore. But the whole thrust of this passage is the topsy-turvydom of Christianity: the weak triumph over the strong, the foolish over the wise, the nobodies over the illustrious. As Joseph Campbell points out, somewhere in The Masks of God I think, “The older shall serve the younger” is not only a description of Jacob’s relationship to Esau (and before them, of Isaac’s to Ishmael) but a recurring motif of the whole Tanakh. Or, to put it in the words of the Mother of God:

He hath shewed strength with his arm:

—he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

He hath put down the mighty from their seat:

—and hath exalted the humble and meek.

He hath filled the hungry with good things:

—and the rich he hath sent empty away.

He remembering his mercy hath holpen his servant Israel:

—as he promised to our forefathers, Abraham and his seed, for ever.

Footnotes

1That is, for the first season. Season Two (which, oddly, wasn’t aired until 2016, when Season One aired in 2012) was moved to Disney XD. I assume Disney XD is different from the Disney Channel proper somehow, but I never summoned the give-a-damn to find out.

2Yes, I will die on the hill that they’re the first people to deserve the word “legendarium” for their creation since Jolkien Rolkien Rolkien himself.

3You may be thinking of the rare verb wizen here (the root of “wizened”), assuming that it got its meaning “to shrivel, wither” via the association of wisdom with old age. I guessed that too, but apparently we are both wrong: it comes not from the Anglo-Saxon adjective wīs, but the Anglo-Saxon verb wisnian or “to dry up.” (In reality the word “wizen” is, of all possible things, an exceedingly distant cousin of “were”!)

4Sort of. Really what’s stuck on the front is a preposition, κατά [kata], which normally means “against,” “down, along, towards,” or “according to, from”; however, like English (and Latin to an extent), Greek likes sticking prefixes and suffixes onto verbs and pronouns to change their meanings, in ways that aren’t always predictable. A good English example is the indefinite pronoun whoever: “ever” is an adverb of time; how on earth does sticking it on the end of a pronoun (and one that already isn’t super specific!) turn it into an indefinite pronoun? The answer, obviously, is that down-up-middle sound people make without opening their mouths that means “I don’t know,” optionally accompanied by a shrug: English just kind of did this and we have to live with it. (Or, more precisely, there probably is an answer, but the kind that you have to listen to a bunch of nerd shit to understand, and that’s not what we’re here for, is it folks.)

5Specifically, I want to save “humiliate” for αἰδέομαι [aideomai]. This is related to the noun αἰδώς [aidōs], an intriguing word—it’s most often translated “shame,” sometimes “modesty” or “reverence,” and “humility” would do. It describes a sense of human limitations which makes us reluctant to do wrong, and that also makes us feel differences of prosperity between one man and another to be undeserved. In this latter aspect especially, I think the closest corresponding element to αἰδώς today is the feeling (as distinct from the belief) that “all men are created equal.” Αἰδώς is also the name assigned to one of the gods and goddesses who lived on earth during the Golden Age, as related by Hesiod. (The greatest of these was Astræa, goddess of innocence and justice; she was the last to depart at the end of the Golden Age, ascending into heaven to become the constellation Virgo.) Whether αἰδώς was more deity or personification is hard to say, but it’s an important element in ancient moral thought.

5This text was not chosen at random, just to be clear. The Mishnah is a compendium of what’s called the Oral Torah, put together in the late second century (and therefore probably not vastly different from the kind of Oral Torah observed by Jesus and in his day); together with a commentary on it known as the Gemara, the Mishnah is one of the constitutive parts of the Talmud. For a more expanded explanation of what “Oral Torah” means, see this post, specifically under the heading “The Least Stroke of a Tongue.”