This post covers the Gospels for the Twelfth and Thirteenth Sundays

after Trinity (a.k.a. the Twentieth and Twenty-First Sundays in Ordinary Time),

as celebrated on 18 and 25 August, 2024 (Year B, weeks 20 and 21).

The Peroration

I’m here finishing my translation of, and commentary on, John 6, which I left off just before Assumption. This post covers the Gospel passages from both this past Sunday and the one before. When last we saw Jesus in the synagogue at K’far Nachum (Capernaum), he was saying, “I am the living bread, which has come down from heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever, and the bread which I will give, it is my flesh, for the life of the world.”

I feel like they made the dudes who

communicate principally through these

red-and-greyscale cartoons in a lab

somewhere that closed in early 1940.

John 6.51-58, 59; 6.60-69, 70-71 RSV-CE

“I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if any one eats of this bread, he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

The Jews then disputeda among themselves, saying, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you; he who eatsb my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day. For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed. He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so he who eats me will live because of me. This is the breadc which came down from heaven, not such as the fathers ate and died; he who eats this bread will live for ever.” This he said in the synagogue, as he taught at Capernaum.

Many of his disciples, when they heard it, said, “This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?” But Jesus, knowing in himself that his disciples murmured at it, said to them, “Do you take offense at this?d Then what if you were to see the Son of man ascending where he was before? It is the spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail; the words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life.e But there are some of you that do not believe.” For Jesus knew from the first who those were that did not believe, and who it was that should betray him. And he said, “This is why I told you that no one can come to me unless it is granted him by the Father.”

After this many of his disciples drew back and no longer went about with him. Jesus said to the twelve, “Will you also go away?”f Simon Peter answered him, “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life; and we have believed, and have come to know,g that you are the Holy One of God.” Jesus answered them, “Did I not choose you, the twelve, and one of you is a devil?”h, i He spoke of Judas the son of Simon Iscariot,j for he, one of the twelve, was to betray him.

John 6.51-58, 59; 6.60-69, 70-71 my translation

“I am the living bread, which has come down from heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever, and the bread which I will give, it is my flesh, for the life of the world.” Then the Jews began fightinga with each other, saying: “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?”

So Jesus told them: “Amen, amen, I tell you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life in yourselves. He who chewsb my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him again on the last day. For my flesh is a true meal, and my blood is a true drink. He who chews my flesh and drinks my blood stays in me, and I in him. Just as the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, he who chews on me, he will also live because of me. This is the breadc that has come down from heaven, not as the fathers ate and died; he who chews this bread, he will live forever.” He said these things teaching in the synagogue in K’far Nachum.

Ruins of the Great Synagogue at Capernaum

(4th or 5th cent.), which may have been built

over the 1st-cent. synagogue. Photo by

Eddie Gerald—CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Then many of his students who were listening said, “A hard word, this one is; who can listen to it?”

And Jesus, knowing in himself that his students are grumbling about this, tells them: “Does this trip you up?d What if you saw the Son of Man going up where he was at first? The Spirit is the life-maker, the flesh is no help; the message which I have told you, it is spirit and it is life.e But there are some of you who do not believe.” For Jesus knew from the beginning which ones did not believe, and who would hand him over. And he said: “This is why I told you that no one can come to me unless it is given to him from the Father.”

From this point, many of his students left off following after him anymore. Then Jesus said to the Twelve, “Don’t you want to go too?”f

Simon the Rock answered him, “Sir, whom would we go to? You have the message of eternal life, and we have come to believe and knowg that you are God’s holy one.”

Jesus answered them: “Did I not select you Twelve? But even one of you is an informer.”h, i (He was talking about Judah, son of Simon ish-Q’rîyoth,j for that “one of you twelve” was going to hand him over.)

Textual Analysis

a. disputed/began fighting: The dissensions among the Jews escalate from different attitudes or interpretations (as in chapters 2-3) into a fully-fledged quarrel (which continues mounting through the close of chapter 8, relaxes slightly in chapters 9-10, and then is brought to fever pitch by the miracle of chapter 11).

An unleavened flatbread of the type common in

the Eastern Mediterranean. Photo by Jonathunder,

used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

b. eats/chews: As Catholic apologists are fond of pointing out (and who am I kidding, I’m not above loving this any more than most Catholics), although some Bibles don’t reflect this fact, the verb here changes. Up to this point, Jesus has been describing eating him with the commonplace verb ἔφαγον [efagon]. In v. 54, he switches to the verb τρώγω [trōgō], a more vivid term—one often used to describe animals. “Munch” or “gnaw” are often cited as useful translations.

c. This is the bread: Strictly speaking, this is not textual commentary; but it is hard to imagine Jesus saying this without gripping his own arms and hands at the same time, or otherwise pointing to the very literal body that is “the bread that came down from heaven.”

d. Do you take offense at this?/Does this trip you up?: Our old friend σκανδαλίζω [skandalizō] is back! See this post for details.

e. It is the spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail; the words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life/The Spirit is the life-maker, the flesh is no help; the message which I have told you, it is spirit and it is life: Okay, this sentence is a little involved, so bear with me. The way it’s often interpreted among evangelicals is as a statement on Jesus’ part that he is speaking figuratively; I don’t think that’s what he’s saying here, though. “These words are spirit” is not a stock expression for being figurative language, or not one I’ve heard of. I haven’t actually seen that expression used anywhere else, even in Scripture. (The only other text I’m aware of that could plausibly be taken that way is Apoc. 11.8—but even there, the revelator uses an adverb, πνευματικῶς [pneumatikōs]; he does not say that the city’s name “is spirit.”)

Yes, I am using that slender excuse to share

one more illumination from the Beatus

Apocalypse, this one of the Dragon giving

his power to the Beast.

The word I’ve rendered “life-maker,” ζῳοποιοῦν [zōopoioun], may have been coined as an allusion to Gen. 1.2, and is the same word used in the Creed about the Holy Ghost, in the phrase “Giver of life” (in Latin, vivificantem). To articulate its relevance here, I’d like to draw on two things: one, a remark made by my friend Joey; the other, the faint but, in my opinion, definite parallels between this discourse and the conversation with Nicodemus in ch. 3. Regarding the latter, both Nicodemus and the crowd at K’far Nachum approach Jesus with enthusiasm, alluding to the miracles he has performed, but are rapidly thrown into perplexity by what he tells them they must do to inherit eternal life (“be born again” and “eat the flesh of the Son of Man,” respectively). In reply, he refers both to the mysterious movement of the Spirit and the drawing of the Father. Both leave unsatisfied—at least, so it appears. Following the “Gospel-as-trial” motif that pervades John, we have in this chapter an explicit reference to an “accuser”; meanwhile, Nicodemus in chapter 3 departs without any clear disposition, only to pop up again in John 7 as an unexpected witness for the defense.1

The former is quite simple. Two or three years ago, on Twitter, my aforesaid friend defined “spiritual” as “existing in the dimension of meaning.” I find this quite helpful: it does away with a lot of what C. S. Lewis called “nursery-thinking” (his go-to example being substance in the Scholastic sense, which he said he could only seem to conceive as something “like very rarefied plasticine”2).

f. Will you also go away?/Don’t you want to go too?: Alongside its atypical treatment of miracles, John also exhibits a quality in Jesus’ personality, something that seems almost like pessimism. I’m not sure what to make of it: God incarnate having a pessimistic streak seems incongruous, but I find it hard to parse his tone any other way.

Woe Unto You, Scribes and Pharisees

(1850), James Tissot

g. we have believed, and have come to know/we have come to believe and know: The “have come to” business in both translations is an artifact of the verb form used here; it’s not difficult to understand, but the explanation is a little involved. I could’ve sworn I discussed the perfective aspect of verbs in a recent post; if I did, I can’t find it now, so here we go.

Verbs have a few different facets, some of which you probably remember from school, like person (first, second, or third) and tense (past, present, or future, plus a few oddities). One facet of verbs that’s rarely taught in schools, certainly not in grade school, is what’s called verbal aspect. Part of the reason it’s so rarely addressed is, aspect and tense are both related and easily confused, on top of which many languages don’t distinguish between them on a grammatical level.3, 4

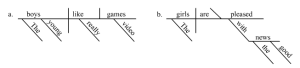

Remember these? Of course not, no one diagrams

sentences anymore. Diagram by Tjo3ya, used

under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

The difference goes like this. Tense is the relationship between (a) the action of the verb, and (b) the time when the speaker is describing that action. If the speaker is describing the action simultaneously with it happening, the present tense is called for; if he’s describing that action later on, he’ll use the past tense; to describe it in advance, he’ll use the future tense. Aspect, on the other hand, is about how complete the action of the verb is: the two most basic forms of aspect are “finished” and “not finished”—or, in Latin, perfectus and imperfectus.

The verbs “believe” and “know” in this verse are both present tense, perfective aspect verbs: they describe actions that are both complete and done in the present. This is a little odd for English speakers! The easiest parallel example I can think of is a sentence like “I’ve finished eating”: the action is complete, but it is still relevant to the present. (Contrast this with a sentence like “I ate,” which is generically past and, if anything, implies that the action is not relevant to the present, at least in the sense of not still being full.)

So, in our text, the believing and the knowing are completed actions, not in-progress. But translating them as “we believed and knew” would suggest either that Peter was going to reference some past occasion on which these achievements were made, or that he was going to contrast their past belief and knowledge with the present somehow (“We knew x, but now y”)—in English, it could even hint that their faith and knowledge were wavering. Hence, despite the Greek not having any helping verb here, “we have come to believe and know” seemed like the best rendering.

h. Did I not choose you, the Twelve, and one of you is a devil?/Did I not select you Twelve? But even one of you is an informer: At first, I took this whole statement on Jesus’ part as a bitter lament, almost like a more elevated version of “Everything I do goes wrong,” save of course that any element of resentment or doubt would have been absent. On reflection, though, I wasn’t sure that any version of that sentiment, however elevated, would survive the removal of sinful bitterness and doubt. (Lament as such can absolutely be sinless—what I’m genuinely unsure of is whether sinless lament can have the specific tinge of bitterness.) I now wonder whether this is, rather, concluding the bread of life discourse on a sort of mixed chord: recognizing the faithfulness of the Twelve with genuine pride (“Did I not select you?”), albeit with an inevitable pang at the same time (“But …”), and the tension of John continues slowly mounting.

Judas’ Remorse (1880) by José Ferras

de Almeida Júnior, which I must say

seems, as a scene, a lot more chill than

I’d have expected.

i. devil/informer: Yet again, I find myself bending one of my own translation rules (the “one Greek word = the same English word in as many contexts as possible” rule). Here, the problem-word is διάβολος [diabolos], “accuser, slanderer; plaintiff.” Obviously there’d be nothing ungrammatical about using “accuser,” “slanderer,” or “plaintiff” in this sentence, but none of them are quite how διάβολος hits here; the impression you get is that of “informant” or “snitch.” Or perhaps, more broadly, “enemy,” but since Jesus leaves the Twelve hanging like this, I decided “informant” was a better fit.

j. Iscariot/ish-Q’rîyoth: I’m interpreting the by-name Iscariot as a Hellenization of ‘ish Q’rîyoth or ish Kerioth, “man [from] Kerioth” (a village in southern Judæa).

Footnotes

1Note, too, that this Pharisee who came to Jesus by night in the beginning was apparently not invited to the overnight trial of Jesus in the end.

2Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer, Letter XIX.

3This isn’t to say that people who speak these languages don’t or can’t understand these differences (as the idiot’s version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis implies); it just means that the grammar of these languages doesn’t do the work of highlighting those differences. For instance, Japanese doesn’t have number in nouns, i.e. there is no differentiation between singular and plural forms: if you’re speaking about a god, a 神 [kami], you use the same form of the word as when you’re talking about several 神, or 神 as a collective class, etc.—but this doesn’t mean Japanese people don’t understand the concept of plurality!

4For those of you who’ve studied Latin, this might surprise you, but in reality, Latin only has three tenses: past, present, and future. You were most likely taught that it has six; this is because your teachers (or the textbook) conflated tense with aspect. Latin does have two aspects, namely the imperfective and the perfective (the former for incomplete actions, the latter for complete actions); and you probably did learn these, but as the “imperfect and perfect tense systems” or some name like that.