This is Part IV of a series. Go to these links for the first three parts: Kingdom Come, A Knot of Bread, and The Price of Pardon.

Le “Pater Noster” [The “Oure Fadir”]1 (1896),

by James Tissot.

We’ve now covered six of the eight clauses of the Lord’s Prayer: the opening address and first three petitions in Part I, the fourth petition in Part II, and the fifth in Part III. Time to knock out the sixth and seventh. These are the clauses of prayer for protection. (The word apotropaic comes from Greek, and literally means “turn-aways”; it’s used in fields like folkloristics and religious studies to describe objects or customs meant to ward off evil. The nazar is a famous, and Near Eastern, example of a popular apotropaic.)

καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμόν,

[kai mē eisenenkēs hēmas eis peirasmon,]

also not may-you-lead us ..into ….trial,

And lead us not into temptation:

After the ego-crushing stuff about forgiveness—something we both have to beg for and aren’t allowed to withhold from others—it may be a positive relief to turn to some “though I walk in the valley of the shadow of death” type stuff! Speaking of which, this is a great clause at which to ask for grace in fighting sins and sin-ward dispositions like resentment, bitterness, hatred, scorn, self-pity, despair, and self-righteousness, which are all apt to make it particularly hard to forgive.

Linguistically, the only notable term here is πειρασμόν (dictionary form πειρασμός), commonly rendered “temptation” or “trial.” Like many Greek words ending with -μός [-mos], it’s an abstract noun, derived in this case from a verb (derivations from nouns or adjectives using this ending also occurred). The verb in question is πειράζω [peirazō]; though it could also mean “to prove,” πειράζω did not mean “try” in the sense of trying a case, but in the more commonplace sense of “attempt, ‘take a shot at'”—though it did bear the secondary sense “to seduce, tempt.” The reason it could mean, or sense in which it could mean, “prove” was the same sense in which we speak of proving grounds,2 like the famous Aberdeen Proving Ground outside Baltimore.

Illuminated capital (14th c.) from an English

missal, showing the binding of Isaac; now

housed in the National Library of Wales.

This is therefore a petition something like “Please don’t put me in situations where I’ll have to ‘show my quality’.” So it turns out the ego hits are still going on, and you’re welcome. Then again, if we’re sensible, maybe we won’t experience this as a blow to the ego: Scenes from the Bible which compelled their central characters to show their quality include things like the sacrifice of Isaac or, for that matter, the Passion (during which our Lord did pray pretty explicitly not to have to endure the πειρασμός he had foreseen). Maybe it’s not so shaming to be told to pray, Please don’t let obeying You be a matter of life and death.

ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ.

[alla rhüsai hēmas apo tou ponērou.]

..but .rescue …us …from the oppressive.

But deliver us from evil.

The seventh and final petition. Two terms here, ῥῦσαι and πονηροῦ (dictionary forms ῥύομαι [rhüomai] and πονηρός [ponēros] respectively), call for comment. The latter has come up on this blog a few times before, so let’s dispose of that first.

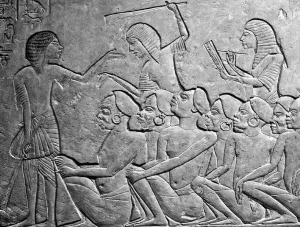

Relief from the tomb of Pharaoh Horemheb3 (r.

1319-1292 BCE), depicting Kushite captives soon to

be sent to Egyptian slave markets. Photo by Mike

Knell, used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license (source).

Πονηρός has come to mean simply “evil” in modern Greek, but originally it signified “toilsome, wearying,” and later “oppressive.” Given the centrality of the Exodus to Israelite and later Judaic4 identity, a development of this kind (toilsome ⇒ oppressive ⇒ evil) in Judeo-Greek was natural and even perhaps inevitable; it would be interesting to know (which I don’t) whether, or how much, its appearance in this prayer influenced the general, language-wide evolution of the word’s meaning.

As for ῥύομαι, it’s not too unusual a word in and of itself, though it has a couple little wrinkles which I find intriguing. One, which you can find discussed in this entry for the word in the online version of Strong’s Concordance, is the association between rescue as an idea and the activity of heroes and the gods (seemingly, an association that was, heh, strong in this word?). Of course, the concept of obtaining help from heaven is kind of implied here regardless, since you are, you know, praying to God, but it’s fun when there’s a special appropriateness in the vocabulary.

The other is the form of the word. It’s a deponent verb, meaning a verb that has a non-active form but an active meaning; deponent verbs are scattershot all over both Greek and Latin. Why do I say “non-active” instead of “passive”? Because Greek has not only the two normal verbal voices, active and passive, but a third, the middle voice.

What the hell is “middle voice”? I’m glad you asked. (You ask very helpful questions at exactly the right moment; I like that about you.) Your first guess might be that it’s for reflexive verbs, which isn’t quite on the money but isn’t far off either. Basically, the middle voice is used when the agent of the verb is also the direct or indirect object—”things done to oneself or for one’s benefit” is a typical explanation of the middle voice. Cooking is a useful example of this: One may cook for one’s own benefit, but one does not (usually or deliberately) cook oneself; so “making” in I’m making myself a sandwich is not a reflexive verb exactly, but its meaning would still be expressed in Koiné Greek by means of the middle voice. In Greek, most deponent verbs are middle-form6 rather than passive form—the passive voice in Greek developed rather later, whereas the middle was an ancient formation, so more irregularities had had time to barnacle up the middle voice than the passive.

So? Well, ῥύομαι does have a related, non-deponent verb, ῥέω [rheō], meaning “to flow” (the ultimate source of the term rhythm). The way ῥύομαι came to mean “rescue, save, deliver” was through a genuinely middle-voice sense, which may have arisen through the various ways we can manipulate objects while swimming in a pond or stream: “to draw to oneself.”

Footnotes

1The word Le indicates that the title of this work is French, yet the title of the prayer is given in Latin (I raise the distinction because it would also have been possible to title the work in Latin, had Tissot felt so inclined). French is of course descended from Latin: The first two words of this prayer in the vernacular are Notre Père, which even now plainly resemble the Latin phrase noster pater (though the Vulgate reverses the order, placing the adjective second, as the Greek does—and given that I understand French normally puts adjectives second as well, I’m not sure why they didn’t for this! but never mind). English and Latin belong to different branches of the Indo-European family, and are thus related only at a much greater remove, so keeping the Latin and translating the French didn’t feel right at all; I therefore opted to render the Latin as Middle English to match the French-to-English part of the title. The fact that I not only felt a need to do this, but wrote a honking great footnote explaining it, tells you pretty much everything you need to know about me and my approach to translation.

2And if by some chance you’ve always wondered, or are now wondering, what those are, proving grounds are places where weapons (especially newly-developed ones) can be tested, and/or where those who use said weapons can be tested for things like their marksmanship under stress. Aberdeen Proving Ground, which belongs to the US Army, was constructed during the First World War, while Baltimore was still one of the nation’s most important port cities.

3Horemheb was the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, the first dynasty of Egypt’s New Kingdom, and something of an odd duck among Egyptian dynasties. Its founder, Ahmose I, had driven out the Hyksos (the first foreigners known to rule the country, though they did not manage to conquer all of it), and the transition from the dominion of the Hyksos back to native rule has been suggested as a possible meaning behind Exodus 1:8, where it says that “there arose up a new king over Egypt, which knew not Joseph.” Most Egyptian dynasties only managed to rule for about a century, but the Eighteenth was in power for over two and a half—at least, it was if we count Horemheb on the end there, who is believed to have been a commoner that married into the dynasty; it also featured two of Egypt’s most notorious rulers: Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE), the woman who, when told that only a king could rule the nation, reacted by simply declaring herself King of Egypt (a move which does show a highly impressive set of balls, no matter how metaphorical they may have been); and Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE), the “heretic pharaoh” who attempted to abolish the rest of the Egyptian pantheon in favor of his preferred cultus of solar henotheism.

4The distinction between these two is drawn essentially by the Babylonian Exile. Before it, one would speak of Israelites and of ancient Israelite religion: after it, of Jews (or perhaps Judahites or Judeans, depending on context) and of Judaism, as the exile is at present believed by scholars to have played a pivotal role in the development of Judaism. Now, I’m admittedly on record as being skeptical of some conclusions drawn by the scholars of ancient Israelite religion. For example, the archæological evidence we have from pre-Exilic Canaan certainly shows that syncretic polytheism was familiar in ancient Israel and Judah, and I readily accept this; however, I’m utterly mystified by the standard scholarly inference that this means the Tanakh is unreliable, when large swaths of the historical and prophetic books (in Christian terminology—in Judaism, most of these5 are referred to as the Former and Latter Prophets) are thunderous tirades against God’s people’s faithlessness, precisely for their practice of syncretic polytheism! However, I see no real reason to doubt that the Babylonian Exile was a hugely formative period for Judaism, nor that it was influenced by Zoroastrianism. Certain developments in Judaism—the growth of any noteworthy belief or interest in an afterlife, for example, or the beginnings of apocalypticism—are, at minimum, contemporary with the cultural exchange between Jews and Persians that presumably began with Babylonia’s fall to Cyrus the Great.

5There are three standard divisions of the Tanakh (the Hebrew Bible): the Torah (the Law, a.k.a. the Pentateuch); the Nevi’im (the Prophets), which are subdivided into Former and Latter; and the Ketuvim (the Writings). The Nevi’im include most of the same books that Christians call “prophetic,” with the exception of Daniel and Baruch, the latter of which is not recognized by Jews as Scripture, but these form only the Latter Prophets. The Former Prophets are the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings; Ruth and the remaining historical books from Chronicles forward are all assigned to the Ketuvim. Note also that Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles are all undivided volumes in the Tanakh; their division into Is and IIs is a convention introduced by the Septuagint. (The only numbered Old Testament books where the numbering is original—though these again are not accepted as inspired by Jews—are I and II Maccabees and, in the Ethiopic canon, I, II, and III Meqabyan. As for the many books of Ezra, their divisions are original but their numbering plainly is not, as is clear from the fact that no linguistic or ecclesiastical tradition can keep the numbering straight for five minutes.)

6Even if you don’t know Greek, you can tell a Greek deponent verb by the ending of its dictionary form. Most normal verbs of that form end with -ω [-ō], besides a handful that end in -μι [-mi]; a deponent verb, however, will instead end in -μαι [-mai] in its dictionary form. Admittedly, just knowing that a verb is deponent doesn’t tell you much about it, but if you’re reading this blog at all, the chances are high that you’re a nerd, and even knowing little factoids like that is fun.