Go here for Part I. Also, you’ll notice that the textual footnotes seem to go directly from a to d; this is because note d actually concerns two words, and becomes fully relevant at the second (by which time two more textual notes have been marked).

Luke 1:39-56, RSV-CE

La Visitación [“The Visitation”] (1500),

by Maestro de Perea.

In those days Marya arosed and went with haste into the hill country, to a city of Judah, and she entered the house of Zechariah and greeted Elizabeth. And when Elizabeth heard the greeting of Mary, the babe leaped in her womb; and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spiritb and she exclaimed with a loud cry, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb! And why is this granted me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For behold, when the voice of your greeting came to my ears, the babe in my womb leaped for joy. And blessedc is she who believed that there would be a fulfillmentd of what was spoken to her from the Lord.” And Mary said,

e“My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for he has regarded the low estate of his handmaiden.

For behold, henceforth all generations will call me blessed;

for he who is mighty has done great things for me,

and holy is his name.f

And his mercy is on those who fear him

from generation to generation.

He has shown strength with his arm,

he has scattered the proudg in the imagination of their hearts,

he has put down the mighty from their thrones,

and exalted those of low degree;

he has filled the hungry with good things,

and the rich he has sent empty away.

He has helped his servant Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

as he spoke to our fathers,

to Abraham and to his posterity for ever.”

And Mary remained with her about three months,h and returned to her home.

Madonna on a Crescent Moon in Hortus Conclusus

(ca. 1450), anonymous.

Luke 1:39-56, my translation

Miriama arosed in those days and went into the highlands with all speed to a city in Judea, and she came into the house of Zekharyah and greeted Elisheva. And it happened that when she, Elisheva, heard Miriam’s greeting, the infant leapt within her, and Elisheva was filled with a holy spirit,b and she exclaimed with a great cry and said: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit within you. And how has this happened to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For see, just as the voice of your greeting came into my ears, the infant within me leapt with gladness. And happyc is she who has had faith that there will be completiond of what was told her from the Lord.”

And Miriam said:

e“My soul magnifies my Lord,

and my spirit is glad for my God and Savior;

because he looked upon the humiliation of his slave,

for see— from now on, they will call me happy, every generation;

because he, the powerful one, has done great things,

and his name is holy;f

and his pity is on generation after generation among those who fear him.

He enacted strength with his arm,

he scattered those who were conceitedg in the thought of their hearts;

he took down the powerful from their thrones and put the humiliated on high,

the hungry, he filled with good things, and the rich he sent out empty.

He took hold of Yisroel, his boy, remembering pity,

just as he told our fathers,

Avraham and his seed for ever.”

The Magnificat in Church Slavonic, penned by

Alexei Zoubov. Note that this is written in the

Glagolitic script, a predecessor of Cyrillic.

So Miriam stayed with her about three months,h and turned back to her own house.

Textual Notes

a. Mary/Miriam | Μαριάμ [Mariam]: Okay, strap in—this one’s kind of involved. As I’ve explained once or twice elsewhere, my philosophy of translation is that, as far as is possible, “one Ancient Greek root = one English root.” Here’s what that means in more detail.

- Say we have some Greek word we’ll call λ (lambda, the Greek alphabet’s equivalent of our l). If λ appears, say, twenty-six times in the New Testament, I want (ideally) to use the same English word (l) to translate λ all twenty-six times.

- But my original formula contained “root,” not “word.” This is because many Greek words come in a large number of complexes—closely related words that show slight modifications to extend the same concept into different parts of speech, create derivative verbs from a basic verb, that kind of thing. (English does this too, as in the relationship among light, enlighten, lighten, lightly, lightness, and lightning.)

- So, if we refer to the whole complex of λ-related Greek words as Λ (also lambda, but capitalized), then to translate Λ, I want to use an English complex (L) whose parts relate to each other in English the same way the parts of Λ relate to each other in Ancient Greek.

- In principle, this extends even to other foreign languages that appear in the Greek text. For instance, Latin is (very distantly) related to Greek, so if a Latin term or phrase appears in the Greek text I’m rendering, I’d ideally like to find a language related to English in roughly the same way Latin is related to Ancient Greek, and then render the Latin into that language in my translation.

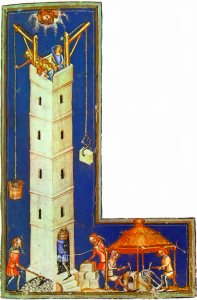

Illumination (c. 1370s) of construction on the

Tower of Babel from a manuscript of Rudolf

von Ems’s Weltchronik [World-Chronicle].

It’s probably not difficult to guess why I hedge in the foregoing with “as far as is possible” and “ideally”! Human languages develop anyhow, mostly without anyone’s conscious design; they certainly don’t ask permission from one another to grow in this or that direction. There are plenty of cases where trying to actually achieve perfect Λ-to-L equivalency would lead to sheer gibberish, and plenty more where it leads to constructions so strained that you can’t imagine an actual human using them for an instant. And the foreign-language-equivalence project is far more likely to be laughably impossible than otherwise. (You could maybe make a very strained case for Old Norse or Gothic being related to Anglo-Saxon the way Latin and Greek were related, but even then, it would only be true at the linguistic level, not the cultural level.)

Now, you may be thinking Okay fine; what does this have to do with names, though? Well, it has a lot to do with names, for two reasons. One is that, while in our day the meaning of all but a handful of names is (a) concealed1 and (b) a tertiary factor in how they get used (many of them have no discernible meaning at all), this was not the norm in the first century. Back then, most names had definite, usually obvious meanings—frequently more than one meaning, especially in Semitic languages, whose very structure invites extensive wordplay. Luckily, I have a sort of insulation here: since the language I’m translating into English is Greek, and a large proportion of the names in the New Testament are Hebrew or Aramaic—and if Semitic and Indo-European languages have any relationship at all, it’s so far back in prehistory that we have no idea what it is—so I don’t have to hunt through Old English lexicons for some natural-sounding way of making “bitter sea” into a credibly usable name! But there is another, rather different, kind of catch.

Due both to layers of cultural transition (Aramaic and Hebrew to Greek, Greek to Latin, Latin to Anglo-Saxon and French, Anglo-Saxon and French to modern English) and the considerable time gap we’re talking about (handily approximated by taking the current year and sticking a comma back in after the first digit), the names of Biblical figures are often different in the original text—sometimes extremely different. Moreover, because English is not really a language but four languages in a trench-coat silently praying that you’ll accept its fake ID, we’ve often borrowed the same Biblical name in two, three, four, five distinct forms (from less or more immediate sources and at different periods). For the name of the Mother of God, Mary is the most familiar English form, but we’ll also most likely recognize alternate forms like Maria, Mariah, Marian, Marie, Meryam, Maureen, Miriam, Moira, and Molly, to name just nine.

The Magnificat in Ge’ez, the liturgical

language2 of Ethiopic Christianity (pre-

dominantly Miaphysite, with a large

Protestant and a small Catholic minority).

To complicate the issue still further, there are place names to think of as well. Many of the places the New Testament refers to have stayed populated since the first century; back then, some of the names these places had were closely related to, or identical with, in-use personal names. Yehudah in a given context might refer to the Ish-Qeriyoth (the man we known as Judas Iscariot), or to the realm he was from (what we, under faint Græco-Roman influence, call Judea). If you’re trying to make the personal names more correct … somehow, are you going to stick to your own logic and adjust the toponyms too—at the cost of making a text that refers to places we read about not only in Bible studies, but in contemporary newspapers, significantly more confusing?

I’ve settled, at least for now, on an extremely unsatisfying compromise: using conventional place-names, but adjusting the personal names to be as close as possible to their original forms—which, often, we have adopted into English from the Old Testament, but haven’t cross-referentially applied in the New. The sad result of that is, we lose a lot of thematic resonances between the two parts of our Bible (like the fact that Jesus had the same name as Moses’ successor, Joshua, or that his mother had the same name as Moses’ sister, Miriam). Luckily, it’s easier to approximate Hebrew and Aramaic names in English than it was in Ancient Greek—although we are missing several important guttural sounds that Semitic languages tend to have (like the q sound in “Iraq”), English still has a larger sound inventory than Greek did.

The twelve heads around the edges are usually

interpreted as the winds, but really they’re just

guys trying to come up with a workable

pronunciation of ħ.

I’ve chosen to do it this way because, though I might be mistaken here, it seems to me that we accept new personal names more easily than new place names (which might just be because we tend to encounter more people than we do places). It therefore seems less likely to ruin the reading experience to use a new name for someone than it would be to do that plus employing a new name for somewhere.

There are six names all told in our text, and one of them is a place name (Judea), so only five need elucidation. I’ve listed them below, in the format (conventional English name): (original Aramaic/Hebrew name, followed by transliteration in brackets) ⇒ (Greek adaption of name appearing in New Testament, with transliteration in brackets)—(name I’ve settled on to use here in bold).

Abraham: אַבְרָהָם [‘Avrâhâm] ⇒ Ἀβραὰμ [Abraam]—Avraham

Elizabeth: אֱלִישֶׁבַע [‘Èlyshevaṛ] ⇒ Ἐλισάβετ [Elisabet]—Elisheva

Israel: יִשְׂרָאֵל [Yiśrâ’êl] ⇒ Ἰσραὴλ [Israēl]—Yisroel

Mary: מִרְיָם [Miryâm] ⇒ Μαριάμ [Mariam]—Miriam

Zechariah: זְכַרְיָה [Z’kharyâh] ⇒ Ζαχαρίος [Zacharios]—Zekharyah

b. the Holy Spirit/a holy spirit | πνεύματος ἁγίου [pneumatos hagiou]: Here (as we’ve occasionally run across elsewhere) we have a difference in interpretation of language, but not a fundamental disagreement about what happened. I believe quite as much as the translators of the RSV did that the holy spirit which thus filled St. Elizabeth was specifically the Holy Spirit; but one wants consistency in how one translates.

The Visitation (ca. 1737), by Gerónimo Antonio

de Ezquerra. Curiously, this version features St.

Joseph, identifiable from the flowering staff in

his hand; Luke says nothing of this.

c. blessed/happy | μακαρία [makaria]: There are two distinct words in Greek commonly translated “blessed.” One is this word—dictionary form μακάριος [makarios], which is a regularized form of an older term, μάκαρ, that goes all the way back to Homer and probably further. Besides “blessed,” there has been a vogue recently for rendering it “happy” in Bibles, while in Classical circles “fortunate” still appears from time to time. I don’t particularly like the vogue—I can’t quite lay my finger on what bugs me about it—but it is arguably the best choice, because of the other Greek word.

That other is εὐλογητός [eulogētos], (lit. “well-spoken-of”), used in the Septuagint to translate the Hebrew בָּרוּך [bâruukh]. This word, and its Greek translation, are used exclusively of God in Scripture. To maintain that kind of signal in English, I believe I’ll want “blessed” available for εὐλογητός, so “happy” is just about the only alternative.

d. arose … fulfillment/arose … completion | Ἀναστᾶσα … τελείωσις [anastasa … teleiōsis]: This could, I suppose, be sheer coincidence. However, I can’t help but notice that, when Mary travels south from the Galilee to Judea proper (a journey that will again be made in thirty-three years’ time), she does so by “arising” (cf. the noun ἀνάστασις [anastasis], “resurrection”), and is ultimately commended for her faith that there would be τελείωσις (cf. the verb τετέλεσται, “It is finished”) of the heavenly promises. This enters an interesting counterpoint with the initial reactions of the apostles to the more famous arising at the other end of the book: thy are said to be “foolish” and “slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken,” until Christ begins to explain in more detail how “everything written about me in the law of Moses and the prophets and psalms be fulfilled.”

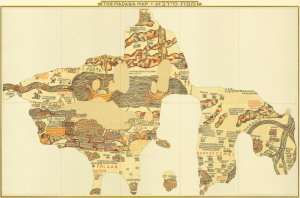

A copy (1954) of the Madaba Map, a 6th-c.

floor mosaic from a church in Madaba in

central Jordan, created by Paul Palmer.

This is also a little funny to me, because, while I’m primed to see a parallel here, the parallel I was primed for isn’t with other parts of the Gospels at all—it’s with a passage from II Samuel. I touched on this about a year ago, and made a handy color-coded set of references for the parallels (and oppositions) in the two texts.

From II Samuel 6:

David arose to bring up from thence the ark of God, the Lord of hosts that dwelleth between the cherubims. And they set the ark of God upon a new cart, and brought it out of the house of Abinadab: and Uzzah and Ahio, the sons of Abinadab, drave the new cart. And Uzzah put forth his hand to the ark of God; for the oxen shook it. And the anger of the Lord was kindled against Uzzah; and God smote him there for his error; and there he died by the ark of God. David was afraid of the Lord that day, and said, “How shall the ark of the Lord come to me?” So David would not remove the ark of the Lord into the city of David: but carried it aside into the house of Obededom the Gittite. And the ark of the Lord continued in the house of Obededom three months: and the Lord blessed all his household. And it was told king David. So David went and brought up the ark into the city with gladness.

And David danced before the Lord with all his might; and David was girded with a linen ephod. So David and all the house of Israel brought up the ark of the Lord with shouting, and with the sound of the trumpet. And as the ark of the Lord came into the city of David, Michal Saul’s daughter looked through a window, and saw king David leaping and dancing before the Lord; and she despised him in her heart. And they brought in the ark of the Lord, and set it in the midst of the tabernacle. … And as soon as David had made an end of offering burnt offerings and peace offerings, he blessed the people in the name of the Lord of hosts. And he dealt among all the people to every one a cake of bread, and a good piece of flesh, and a flagon of wine. So all the people departed every one to his house.

From Luke 1:

Mary arose in those days, and went into the hill country with haste, into a city of Juda; and entered into the house of Zacharias, and saluted Elisabeth. And it came to pass, that, when Elisabeth heard the salutation of Mary, the babe leaped in her womb; and Elisabeth was filled with the Holy Ghost: and she spake out with a loud voice, and said, “Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. And whence is this to me, that the mother of my Lord should come to me? For, lo, as soon as the voice of thy salutation sounded in mine ears, the babe leaped in my womb for joy. And blessed is she that believed: for there shall be a performance of those things which were told her from the Lord.”

And Mary said, “My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Savior. For he hath regarded the low estate of his handmaiden: for, behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. … He hath shewed strength with his arm; he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree. He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich he hath sent empty away. He hath helped his servant Israel, in remembrance of his mercy; as he spake to our fathers, to Abraham, and to his seed for ever.” And Mary abode with her about three months, and returned to her own house.

e. (the Magnificat): This hymn is known in the West by its first Latin word, magnificat, meaning “magnifies” or “exalts.” It is, to all appearances, modeled closely upon the Song of Hannah (which appears in I Samuel 2); in context, Hannah was rejoicing not only in Samuel’s birth, but what it meant for herself—relief from the needling of her husband’s other wife, Peninnah (which I touched on in the meditation on the final text in this post); and she seems also to have a premonition of what Samuel’s role in the history of the Israelites will be (remember that it was through Samuel that both the monarchy as such and the Davidic monarchy specifically were instituted).

The Magnificat in a 15th-c. French Book of Hours.

Here, the general concept of a song of victory is both repurposed and universalized (“every generation,” “generation after generation”)—a recurring theme in Luke. The same is true of the hymn spontaneously sung by St. Zechariah shortly hereafter (vv. 68-79, referred to as the Benedictus3), whose accent is more on rescue from enemies than the glorification of the downtrodden, though both hymns touch on both themes. Both the Magnificat and the Benedictus are said daily (with a very few exceptions) by clergy and consecrated religious in the Catholic, Miaphysite, and Orthodox Churches, with use varying as to which hymn is used in the morning office of prayer and which is said in the evening; in the West, the Magnificat is said at Vespers, a.k.a. Evensong.

f. holy is his name/his name is holy | ἅγιον τὸ ὄνομα αὐτοῦ [hagion to onoma autou]: The concept of the Lord’s name is a significant one throughout the Bible; at times, it almost seems to assume the status of an autonomous being, as when he speaks of doing things “for the honor of his name.” Certainly the disclosure of the name of God to Moses in Exodus 3:13-17 is, and is intended by its author to be, one of the most momentous passages in the Torah. Names were treated with greater gravity in ancient cultures in general. Even in the European tradition, we find material like Odysseus’ handling of the man-eating cyclops Polyphemus (a son of Poseidon). He slyly gives his name at first as Οὔτις [Outis], “Nobody,” so that when he and his men blind the creature’s single eye, it can only cry out to its fellows that “Nobody is killing me”4—only to ruin it at the end by getting cocky and shouting his real name back as they escape, thus allowing Polyphemus to tattle to Poseidon about whom to avenge his monstrous child’s injury upon. Contrast this with the cryptic encounter between the patriarch Jacob and “a man” in Genesis 32:24-32 (apparently a theophany, likely in the form of an angel), who both renames Jacob as Israel and resolutely refuses to disclose his own name—which is partly why Exodus 3 packs such a punch when it arrives.

Landscape With Jacob Wrestling the Angel

(before 1676), by Pierre Patel.

This is because names, like messengers, were treated as extensions of the person themselves, even more so in Semitic cultures than in Greek. This is probably why the rite of exorcism lays such an emphasis on forcing the demon to reveal its name—something the Lord did sometimes, but not always (see Mark 5:1-13 and contrast it with 1:21-27, for instance). I’ve genuinely begun to wonder whether “the name of the Lord,” in at least some contexts, might actually be a subtle intimation of the distinct Personhood of the Holy Ghost.

g. proud/conceited | ὑπερηφάνους [hüperēfanous]: There are a few different words for pride in Greek; ὕβρις [hübris]—the kind of insolence that invites the vengeance of the gods—is perhaps the most familiar in English, while Classicists and some philosophy students will recognize μεγαλοψυχία [megalopsüchia], the “proper pride” or grandeur of a noble soul. This kind, ὑπερηφανία [hüperēfania], breaks down into parts meaning “over” (the preposition) and something like “bright, shiny” or potentially “loud”; in a more casual context, “brassy” wouldn’t be too bad a translation. This is especially the kind of pride traditionally spoken of by moralists as “vainglory”—the kind that feeds on others’ admiration and is, accordingly, specially devastated by public disgrace (as contrasted with the slightly more sophisticated pride that, genuinely, “doesn’t need the admiration of the likes of them“).

h. three months | μῆνας τρεῖς [mēnas treis]: The implication here would seem to be that the Mother of God rushed down to Judea not only to deliver her own miraculous news, but with an eminently practical purpose too: so that she could assist St. Elizabeth when she gave birth. On the other hand, it is also possible that her flight was (at least in part) a necessity imposed by her own pregnancy.

Joseph’s Dream (c. 1645), by Rembrandt van

Rijn. Judging from the presence of the Virgin

and the faintly-discernible cow’s head, this is

the dream prompting their flight to Egypt.

We know St. Joseph’s plan, even before coming to accept “her story” (as it was surely called), had been to “divorce her quietly,” because he did not want her exposed to public shaming—which suggests at any rate that the matter had not yet become common knowledge. And we may be certain that in a tiny, rural village like Nazareth, whatever was anybody’s business in the morning was everybody’s business by nightfall, so St. Joseph’s intentions can’t have been formed long after the pregnancy itself.

What we don’t know is how SS. Joachim and Anne, the Virgin’s parents, reacted. The Church’s later canonization of them (albeit by acclamation5) certainly suggests that, at minimum, they “came around,” and it’s perfectly possible that they received it well from the first. But … would most parents? And would it necessarily be a lack of faith that moved them not to? I tend to think—and I don’t view this as impugning their holiness, or even as a very grave criticism—that they probably didn’t believe her at first. It’s possible that one or both of them were very angry; even if they did believe her, it’s likely that other relations didn’t, and were outraged with her; if Joachim or Anne or both did believe Mary, said relations were probably just as outraged with her embarrassing, gullible parents. I don’t think it’s off the cards that physical violence may have been threatened (at least to the extent of a whipping, then quite a common punishment for wrongdoing of all sorts). But even if any familial anger was restrained from this, it might still have been a smart move to get out of Dodge for a while.

Either way, Mary is not mentioned in the subsequent narrative of the birth of St. John the Baptist. If she did stay for the delivery itself, my guess is that she returned to Nazareth fairly promptly afterwards, maybe even before the circumcision and naming.

A 16th-c. Ottoman depiction of the infant Yahya

(the name used for St. John the Baptist in

Islam)6 held by two angels.

Footnotes

1When I say “concealed,” I mean simply that a great many of our names are borrowed either from foreign languages, or from periods of English sufficiently ancient that we no longer recognize their significance. There are certainly exceptions: you meet the occasional Faith, Joy, Marshall, Mason, or Raven. But these names are recognizably unusual when set beside “meaningless” names, even those of specifically British stock: the Alfreds, Edgars, Jennifers, Leslies, and Winifreds of the world. (Jennifer is technically Cornish, not Anglo-Saxon—it’s cognate with the Welsh name Gwenhwyfar, which was turned by French poets into Guinevere—but its familiarity to the ear and eye place it, for our purposes, with the “meaningless” names we inherit from Anglo-Saxon.)

2Ge’ez, and its associated script, are also used by Beta Israel, the Ethiopian Jewish community. The writing system for this language is known as fidäl in Amharic, the modern vernacular descended from Ge’ez—the Italian to its Latin, as it were. Fidäl is an interesting variety of script; the scripts we are most familiar with are alphabets (like the Roman or Greek), which have signs for consonants and vowels alike, and abjads (like the Arabic or Hebrew systems), which have signs for consonants and treat vowel marking as optional, but fidäl is neither: it is an abugida, a type of script in which consonantal signs are basic, but are modified in some way to indicate the following vowel. The Devanāgarī script of India is a beautiful example of an abugida, and the Canadian Aboriginal syllabary (employed by speakers of Algonquian and Inuit languages) is more exactly an abugida as well; there is also an argument to be made that Tolkien’s Elvish letters, the tengwar, are an abugida.

3Not to be confused with the Benedicite, benediction, or the Benedictines. Sorry, Latin Catholicism is just like this.

4I have not seen this topic elsewhere broached, but I believe this is the earliest recorded instance of a “who’s on first” joke. Insofar as such jokes are metadiscourse and therefore postmodernism, we can therefore safely blame Homer for modern Academe.

5Canonization was a rather fuzzier process before the thirteenth century or so; for a long time, the consensus of the faithful was the instrument of many things, including the canonization of saints. The, ahem, messiness this could lead to moved the clergy to restrict this function to the episcopate, and ultimately led the popes to restrict it to themselves. However, it was not felt either appropriate or necessary to “go back” and invalidate earlier canonizations—perhaps, not least because the prospect of a tribunal discussing whether people like St. John the Evangelist or the Mother of God met the procedural qualifications for recognition as saints (and worse, of finding a “devil’s advocate” for their causes) might have felt just a little too blasphemously ridiculous to countenance.

6Say what one will about Islam, “Yahya” is closer in sound to the original יוֹחָנָן [Youchânân] than “John” is, at any rate.