Scratch ‘n’ Sniff

I’ve touched on the topic of leprosy before, back when I was doing the Gospel of Mark. (Please be aware, there are one or two inaccuracies in that post that I need to go back and correct.)

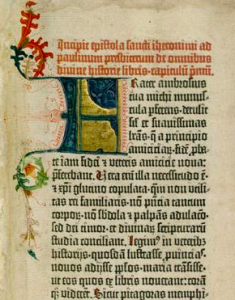

14th-c. illumination of two lepers being

refused entry to a town.

Today, the word leprosy indicates what is also called Hansen’s disease (after Gerhard Hansen, who in 1873 discovered Mycobacterium lepræ, one of two microörganisms which can cause the disease—the other is M. lepromatosis1). It typically causes sufferers an inability to feel pain, and can also result in poor eyesight, catarrh, dry scalp, skin lesions, and muscle weakness, among other symptoms.

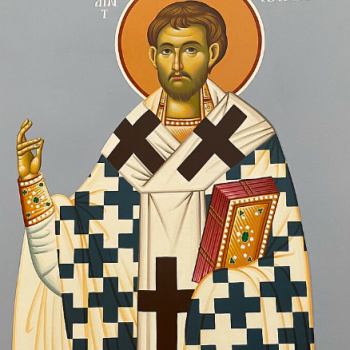

St. Damien of Moloka’i is so named because he ministered to a leper colony on the island of that name in the Kingdom of Hawai’i.2, 3 St. Damien eventually contracted the disease himself, but, despite its reputation, leprosy actually has a fairly low transmission rate—only about 5% of people who are exposed to M. lepræ go on to develop the disease. This was not well understood in the Middle Ages (hence the illumination above, which is only too true to life), let alone the ancient world: the ancient Greeks were surprisingly astute in some aspects of their medical ideas and practices, but they never cottoned on to germ theory.

This was a little bit more the vibe.4

Tzaraath

However, Hansen’s disease is now generally agreed not to be the disease referred to in Leviticus 13-14 as צָרַעַת [tzârauath]—nor, in fact, is it what the Greeks meant by the term λέπρα [lepra], which indicated psoriasis, eczema, and similar skin conditions. As a result, the disease outlined in the Torah is increasingly referred to today simply as tzaraath, the typical transliteration of the Hebrew term.

Certain qualities do distinguish tzaraath from modern-sense leprosy. Note that discoloration—yellowing, reddening, whitening, or turning green—is always mentioned as part of tzaraath (though not all discolorations were defined as symptoms); leprosy in the modern sense can involve reddening of the skin, lesions, and a dry scalp, but other symptoms like eye trouble, loss of sensation in the extremities, and voice alterations are entirely absent from the Torah’s diagnostic criteria. Also conspicuous is the fact that tzaraath could afflict not only people, but garments (if made of wool, linen, or leather) and even houses—I believe some translations render the word as “mildew” in these non-human cases, inconsistently.

It also stands out that, for tzaraath, the Israelites were supposed to consult a priest. I’m not sure, but I believe this is the only disease for which the Torah imposes such a thing; the Levitical priesthood certainly did not fulfill medical functions in general in ancient Jewry (or if it did, there is no hint of this in any part of the Tanakh). Doctors had their profession, and Levites had theirs: the Torah notes certain ritual consequences of this or that bodily phenomenon, which would no doubt have applied to the sick, but it does not conflate the medical sphere with the sacerdotal.

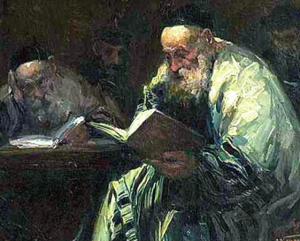

Talmudysci [Talmud Readers] (ca. 1930?),

by Adolf Behrman.

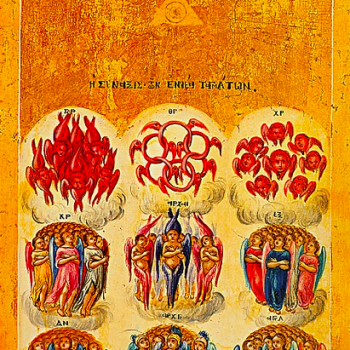

Seven Diseasing Sins?

Rabbinic literature5 indicates that tzaraath is unlike other diseases in two specific ways: first, that it is a direct punishment for certain sins (an idea which, if it were applied to diseases in general, would be implicitly contradicted by the book of Job); and second, that it can only affect Jews—Gentiles, even if they, their clothing, or their houses exhibited the symptoms described in the Torah, would not be held to have contracted tzaraath (though they might be afflicted with something else).6 Seven sins in particular were held liable to punishment with tzaraath:

- perjury

- murder

- illicit sexual intercourse

- theft

- malicious gossip

- stinginess

- hubris

The first, fifth, sixth, and seventh items on that list might strike some readers as ridiculous, but it should be borne in mind what kind of society these laws were designed for. Perjury was the kind of offense that imperiled the basic fabric of society in the ancient world. My favorite Tolkien YouTuber, Girl Next Gondor, has an excellent video essay on the topic, which is just over thirty minutes long; she herself cites a blog post on the subject of oaths by Bret Devereux, if reading suits you better than listening. The fifth, meanwhile, should take very little imagination to see as something that can be deadly serious, in the country which played host to the Salem Witch Trials.

Similarly, the sixth sin here, stinginess, may begin to seem like a bigger deal even today, if we put it in the context of things like debt. Think for a moment about the power that medical or college loan debt have to ruin people’s lives. Or imagine if Martin Shkreli had not been forced to release his financial stranglehold on life-saving medicine.

Phaëthon (1878), by Gustave Moreau.7

As for the last, well, even outside the Bible, we are familiar with the idea that arrogance calls the wrath of the gods down upon itself. Classical pagan and Judaic sources alike agreed that extreme pride is an affront to heaven, and the Christian taxonomy of sins, which makes pride both the worst of them and the root of them, draws on Athens as well as Jerusalem.

New Testament Lepers

This account of tzaraath is not directly alluded to in the Gospels; no explanation for it is referenced. As far as I can tell, this was a standard element of Judaic doctrine in the time of Jesus, though I am not sure of this. Many Biblical instances of those who were afflicted with tzaraath—Miriam, Joab, Gehazi, Uzziah—do line up with some of these seven offenses (specifically the fifth, second, fourth and/or sixth, and seventh). Then again, one more Biblical sufferer from tzaraath was Naaman, who should have been excluded from the disease as a Gentile; at least, a presumptive Gentile.8

The salient fact about lepers in the time of Christ seems to have been, simply and solely, that they were outcasts. It’s hard to fully blame mainstream society for this; however mistaken the belief was,9 it was nevertheless widely believed that lepers were highly contagious. But the fact remains, lepers were not unlike Dalits in India (i.e. “untouchables”), and were probably seen as responsible for their condition.

Luke 17:11-19, RSV-CE

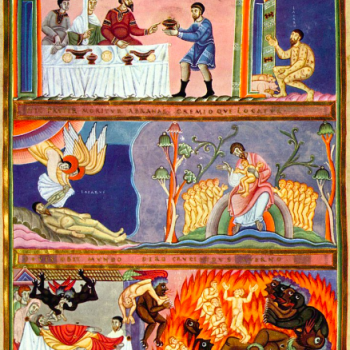

Cleansing of the ten lepers from the 11th-c.

Codex Aureus of Echternach (a city in what

is now Luxembourg).

On the way to Jerusalem he was passing along between Samaria and Galilee. And as he entered a village, he was met by ten lepers, who stood at a distance and lifted up their voices and said, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us.” When he saw them he said to them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went they were cleansed. Then one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, praising God with a loud voice; and he fell on his face at Jesus’ feet, giving him thanks. Now he was a Samaritan. Then said Jesus, “Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine? Was no one found to return and give praise to God except this foreigner?” And he said to him, “Rise and go your way; your faith has made you well.”

Luke 17:11-19, my translation

And it also happened on his journeying to Jerusalem that he was going through in between Samaria and the Galilee. And when he came near a certain village, ten leprous men encountered him, who stood away off, and they raised their voice, saying: “Jesus, chief, take pity on us.”

And seeing them, he told them, “Go, show yourselves to the priests.” And it happened that on their way off, they were cleansed. One of them, seeing that he was healed, returned, glorifying God with a loud voice, and he fell on his face at his feet, thanking him; and he was a Samaritan.

In response, Jesus said, “Weren’t ten cleansed? Where are the nine? Are none found to have returned to give glory to God except this alien?” And he told him, “Rise, go; your faith has saved you.”

Textual Notes

a. On the way to Jerusalem he was passing along between Samaria and Galilee/And it also happened on his journeying to Jerusalem that he was going through in between Samaria and the Galilee | Καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ πορεύεσθαι εἰς Ἰερουσαλὴμ καὶ αὐτὸς διήρχετο διὰ μέσον Σαμαρείας καὶ Γαλιλαίας [kai egeneto en tō poreuesthai eis Ierousalēm kai autos diērcheto dia meson Samareias kai Galilaias]: My English wording here is a tad awkward, because the author of Luke is doing a couple things that are good grammar in Greek but don’t have clean one-to-one equivalents. First, he’s using an infinitive (πορεύεσθαι) as a gerund, or verbal noun; Spanish does this too, as you’ve seen if you’ve ever noticed a sign saying No fumar (literally “Not to smoke” but with the meaning “No smoking,” avoiding the direct imperative probably out of politeness). He’s also using καὶ twice, a word that’s normally extremely simple but can on rare occasions make a nuisance of itself. Its most-literal-possible rendering is “also,” from which meaning it nearly always amounts to “and,” and is usually so translated; but “also” or, more rarely, “too” can be what it means here and there. Since Luke has so little structure (either topical or chronological), it’s natural that some examples of “and this also happened” should emerge, but woe to the translator before whom they emerge, for they will be apt to annoy him.

b. ten lepers/ten leprous men | δέκα λεπροὶ ἄνδρες [deka leproi andres]: The wording here does state specifically that it was ten males with leprosy—apparently a little colony unto themselves.

c. their voices/their voice | φωνὴν [fōnēn]: The use of the singular “voice” here may be a figure of speech indicating their unanimity. Alternatively, perhaps just one of them served as the “spokesman” for the group.

d. master/chief | ἐπιστάτα [epistata]: This word occurs only seven times in the New Testament, all of them in the Gospel of Luke; if it looks familiar, it’s possible you recollect it from the miraculous catch of fish by which Jesus hooked St. Peter, back in chapter 5 (the word is discussed in note d of this post).

The hills of Samaria, as photographed in 2011.

Photo by Wikimedia contributor Quail (source).

e. giving him thanks/thanking him | εὐχαριστῶν αὐτῷ [eucharistōn autō]: This is a standard term for thanking someone; it is not a coincidence that it so closely resembles the word “Eucharist” (from εὐχαριστία [eucharistia]), which has long been associated with the thank-offering outlined in Leviticus 7, among other sacrifices.

f. this foreigner/this alien | ὁ ἀλλογενὴς οὗτος [ho allogenēs houtos]: Hyper-literally, ἀλλογενὴς means “other-born.” As conciliatory as Luke often is, this agrees with the depiction of Jesus in both Matthew and John, as well as elsewhere in the Third Gospel: he treats them with the same courtesy he shows to Gentiles (compare e.g. Matthew 8:5-13 with John 4:5-26), and, unlike some contemporary Jews would, does not refuse to eat and drink with them; nonetheless, he does treat them precisely as Gentiles, not Jews (compare this text with Matthew 10:5-6, or take note of John 4:22 in particular).

Exactly how this is to be reconciled with the idea that tzaraath could only affect Jews, I don’t know. It could be a sign that the rabbinic interpretation of tzaraath wasn’t correct in the first place, but I’m reluctant to go with, well, such an easy explanation, without something concrete in the New Testament to back it up. (Matthew 23:2 seems to me to suggest that our presumption should be in favor of the standard Pharisaic interpretation of the Torah in the first century, absent positive evidence otherwise—though admittedly, discerning what that interpretation was is sometimes difficult.) It is not the only example in either contemporary Judaic or primitive Christian literature of Samaritans seeming to have a kind of in-between status, halakhically speaking: not Jews and yet not really Gentiles. It is worth pointing out that the scandal of opening the Church to the Gentiles in the book of Acts is broached only when St. Peter goes to visit St. Cornelius, not when SS. Philip the Deacon, Peter, and John evangelize Samaria.

17th-c. Georgian illumination of the Israelites

fighting King Hadadezer of Aram (possibly

the king Naaman served, possibly the same

person as Ben-Hadad II).

The fact that the Samaritan—from the sound of things, the lone Samaritan in the group, though we aren’t explicitly told—is the only one of the ten to come back and say “thank you” carries in it a faint echo of the story of Naaman. Compare this:

II Kings 5:1-19

Now Naaman, captain of the host of the king of Syria, was a great man with his master … but he was a leper. And the Syrians … had brought away captive out of the land of Israel a little maid; and she waited on Naaman’s wife. And she said unto her mistress, “Would God my lord were with the prophet that is in Samaria! for he would recover him of his leprosy.” …

And the king of Syria said, “Go to, go, and I will send a letter unto the king of Israel.” And he departed, and took with him ten talents of silver, and six thousand pieces of gold … And he brought the letter to the king of Israel, saying, “Now when this letter is come unto thee, behold, I have therewith sent Naaman my servant to thee, that thou mayest recover him of his leprosy.” And … when the king of Israel had read the letter, that he rent his clothes, and said, “Am I God, to kill and to make alive, that this man doth send unto me to recover a man of his leprosy? … see how he seeketh a quarrel against me.” And it was so, when Elisha the man of God had heard that the king of Israel had rent his clothes, that he sent to the king, saying, “Wherefore hast thou rent thy clothes? let him come now to me, and he shall know that there is a prophet in Israel.”

So Naaman came with his horses and with his chariot, and stood at the door of the house of Elisha. And Elisha sent a messenger unto him, saying, “Go and wash in Jordan seven times, and thy flesh shall come again to thee, and thou shalt be clean.” But Naaman was wroth, and went away, and said, “Behold, I thought, ‘He will surely come out to me, and stand, and call on the name of the Lord his God, and strike his hand over the place, and recover the leper.’ …” So he turned and went away in a rage. And his servants came near, and spake unto him, and said, “My father, if the prophet had bid thee do some great thing, wouldest thou not have done it? how much rather then, when he saith to thee, ‘Wash, and be clean’?” Then went he down, and dipped himself seven times in Jordan …: and his flesh came again like unto the flesh of a little child, and he was clean.

And he returned to the man of God … and stood before him: and he said, “Behold, now I know that there is no God in all the earth, but in Israel: now therefore, I pray thee, take a blessing of thy servant.” But he said, “As the Lord liveth, before whom I stand, I will receive none.” … And Naaman said, “Shall there not then, I pray thee, be given to thy servant two mules’ burden of earth? for thy servant will henceforth offer neither burnt offering nor sacrifice unto other gods, but unto the Lord. In this thing the Lord pardon thy servant, that when my master goeth into the house of Rimmon to worship there, and he leaneth on my hand, and I bow myself in the house of Rimmon: when I bow down myself in the house of Rimmon, the Lord pardon thy servant in this thing.” And he said unto him, “Go in peace.” So he departed from him …

… with a similarly-highlighted version of our Gospel text:

And it came to pass, as he went to Jerusalem, that he passed through the midst of Samaria and Galilee. And as he entered into a certain village, there met him ten men that were lepers, which stood afar off: and they lifted up their voices, and said, “Jesus, Master, have mercy on us.” And when he saw them, he said unto them, “Go shew yourselves unto the priests.”

And it came to pass, that, as they went, they were cleansed. And one of them, when he saw that he was healed, turned back, and with a loud voice glorified God, and fell down on his face at his feet, giving him thanks: and he was a Samaritan.

And Jesus answering said, “Were there not ten cleansed? but where are the nine? There are not found that returned to give glory to God, save this stranger.” And he said unto him, “Arise, go thy way: thy faith hath made thee whole.”

What to make of the parallels, I’m not sure; however, given Naaman’s status as a convert to Judaism (in some sense), it’s possible that this story is an adumbration of the opening of the Church to the Gentiles.

g. has made you well/has saved you | σέσωκέν σε [sesōken se]: There is (so far as I know) simply no English verb that will do to cover the whole range of meaning in σῴζω [sōzō], which σέσωκέν is a form of; its two most basic meanings are “to heal” and “to save.” In Romance languages, descendants of the Late Latin salvāre comfortably do the job; this is why, in the Divine Comedy, Dante is able to swoon over the double meaning when his beloved Beatrice tells him “Salute” on the street one day—which was a normal greeting meaning “[your] health,” but could also mean “salvation.” (English, by contrast, has evolved far enough that even the relationship between save and safe is not transparent to most speakers: something we have made sure in the past to save must now be described with the participle saved, while if we cause something to be safe over a period of time, we can convey that meaning only by saying that we keep it safe.)

Triumph of Faith Over Idolatry (late 17th-

early 18th-c.), by Jean-Baptiste Théodon.

Photo by Wikimedia contributor Jastrow

(source).

Footnotes

1M. lepromatosis is apparently native to the Americas (or has at any rate been present here since before the Columbian era). M. lepræ, on the other hand, seems to have been an Old World disease before 1492. Neither is believed to have been present in Polynesia until the nineteenth century.

2Hawai’i did not become a US colonial possession until 1898 (attaining statehood in 1959, seven and a half months after Alaska). Until 1894, it was an independent kingdom; that year, American interests overthrew the queen and established the Republic of Hawaii. However, the intended US annexation did not immediately take place, since President Grover Cleveland was opposed to imperialism: his successor, William McKinley, annexed Hawaii.

3St. Damien of Moloka’i, a.k.a. Fr. Damien de Veuster, ministered to a lepers’ colony on the island of Moloka’i from 1873 until his death in 1889, five years after contracting leprosy. Before his death, Fr. de Veuster was recognized for his efforts by King David Kalākaua, Hawai’i’s second-to-last monarch (the very last being Queen Lili’uokalani, who visited Moloka’i in person before her accession), granting him the title of Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua.

4This image was obtained via Pinterest; since it is describing (in a humorous idiom) real historical attitudes toward lepers and leprosy, it is protected under the fair use doctrine, which among other things covers the reuse of images of this nature for educational purposes; it in no way impinges on the market of, nor creates any kind of replacement for, the episode of The Simpsons from which it has been isolated, still less the series as a whole.

5Specifically: the Mishnah, of which I have a hard copy of the Herbert Danby translation I can consult (halakhah [see footnote 2 of this post] concerning tzaraath are contained in the Sixth Order, טָהֳרוֹת [Ṭâhàrouth], “Purities,” in its third tractate, נְגָעִים [N’ghâuym], “Plagues”); and the Babylonian Talmud, for which I rely on the edition generously made available on Sefaria.

6In the absence of the Temple, which is required for the purification ritual, Jews do not generally observe the laws of tzaraath today, and most hold that tzaraath proper (i.e., as a direct divine punishment) no longer occurs.

7In myth, Phaëthon is a standard emblem of hubris, alongside figures like Icarus, Niobe, and Tantalus (as well as historical persons like Croesus). Phaëthon was a mortal son of Helios—usually with a sea-nymph, though in a few tellings his mother is human. To prove his parentage, the boy prevailed on his father to let him drive the sun-chariot for one day; but, being a mortal, he was unable to control the chariot (and his careening too far from the earth at one point and much too close to it at another afforded a fairy-tale explanation for why, relative to Greece, the north was permanently cold and the south permanently hot). In the end, to prevent any further damage to creation, Zeus killed Phaëthon with a thunderbolt.

8The same might possibly be true of Job. However, some of the details of Job suggest that he is not intended to be a historical person (note the lack of genealogy, for example), and it is certainly difficult to say from the text alone whether he should be read as a Gentile, a Jew, or somehow neither; moreover, while he is afflicted with “boils” or “sores,” it isn’t at all clear that this is meant to be tzaraath.

9If tzaraath were the culprit, and the belief that it was a specialized divine punishment was correct, then presumably it would only affect the guilty and would not be the sort of thing you could “catch.” If it were leprosy in the modern sense, as discussed above, the transmission rate of Hansen’s disease is actually quite low. If it were some other likely candidate for being called λέπρα in Ancient Greek, such as psoriasis, that’s an autoimmune issue and isn’t contagious at all.