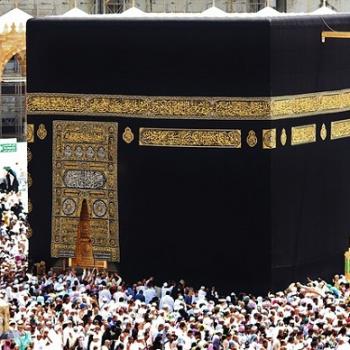

Among the many campaign promises and bigoted viewpoints and rallying cries that President Donald J. Trump campaigned on, one that was loudly and definitively supported by his base was his proposed ban on Muslims. He literally campaigned on banning Muslims, saying until he and his future administration could figure things out, he would push for a complete and total shut down of all Muslims entering the United States.

Trump spoke about how “Islam hates him.” Time and time again on the campaign trail and after election he spoke against Muslims. He spoke of banning Muslims, his supporters spoke of banning Muslims. He received their votes for many reasons, among which was banning Muslims. And then he became president and signed the executive order for the Travel Ban, aka the #MuslimBan.

Now the Supreme Court upheld Trump’s travel ban, arguing in the majority opinion that there was no evidence that Trump was discriminating against Muslims. As summarized in this NBC News article:

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, made it clear that the court viewed the ability to regulate immigration as squarely within a president’s powers, and he rejected critics’ claims of anti-Muslim bias.

“We express no view on the soundness of the policy,” Roberts wrote.

After a series of federal court rulings invalidated or scaled back earlier versions of the travel ban, the decision is a big win for the administration and ends 15 months of legal battles over a key part of Trump’s immigration policy, which opponents attacked as a dressed-up form of the Muslim ban that Trump promised during his 2016 campaign. …

Chief Justice Roberts went on to write in his majority opinion (that other four conservative justices signed onto, as the decision was split on party lines):

The text says nothing about religion. Plaintiffs and the dissent nonetheless emphasize that five of the seven nations currently included in the (ban) have Muslim-majority populations. Yet that fact alone does not support an inference of religious hostility, given that the policy covers just 8 percent of the world’s Muslim population and is limited to countries that were previously designated by Congress or prior administrations as posing national security risks.

I guess it didn’t matter a whit anything Trump said in the months leading up to the Muslim Ban. None of that constituted an anti-Muslim bias. I have to go with Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who (along with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg), wrote in her dissent that based on the evidence in the case,

“a reasonable observer would conclude that the Proclamation was motivated by anti-Muslim animus.”

She said her colleagues on the court arrived at the opposite result by “ignoring the facts, misconstruing our legal precedent, and turning a blind eye to the pain and suffering the Proclamation inflicts upon countless families and individuals, many of whom are United States citizens.”

The Supreme Court’s decision today upheld the third iteration of the Muslim ban. What does that entail, and how does it differ from the first and second version of the ban? The Christian Science Monitor sums it up here:

The ban at issue is the second version of an executive order regarding immigration. The first order, authored with limited input from federal immigration agencies and issued weeks after Trump took office, banned for 90 days entry for citizens from Iraq, Iran, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen, and banned the admission of all refugees for 120 days (or, for refugees from Syria, indefinitely). The Trump administration has cited national security interests as the justification for the order, but critics instead see it as a veiled effort to implement a “Muslim ban” he promised during his presidential campaign.

After mass protests and successful legal challenges around the country, Trump issued a revised executive order in March. The new order removed Iraq from the list of banned countries, included refugees from Syria in the 120 day-ban, and addressed several perceived legal flaws in its predecessor, such as excluding green card holders and specifying the links to terrorist organizations in the other six countries. The 90-day ban was going to expire at midnight Sunday, prompting the Trump administration to issue its new executive action.

Effective Oct. 18, the new proclamation indefinitely restricts travel for citizens from Iran, Syria, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen, as well as North Korea, Chad, and some government officials from Venezuela. The new restrictions are “conditions-based, not time-based” an administration official told The Washington Post, and vary by country. If security conditions improve in a country, it seems, restrictions could be relaxed or removed. Sudan has been removed after agreeing to accept large numbers of Sudanese nationals deported from the US, according to news reports.

Reactions to the Supreme Court decision were full of fury, righteous anger, sorrow and pain. Even more painful was knowing this was a matter of history repeating itself, a decision in a line of shameful decisions made by the Supreme Court — Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), which ruled that black people were not entitled to the same citizenship rights as white people; Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which upheld the separate but equal standard and established a sort of apartheid as the law of the land; and, of course, Korematsu v. United States, which determined that Japanese internment during World War II was constitutional and upheld the internment camps of thousands of Japanese Americans.

Nihad Awad, executive national director of CAIR, said in a press conference that the decision “has given the Trump administration a free hand to reinject discrimination against a particular faith back into our immigration system, which was rejected more than 50 years ago.

Law professor Khaled Beydoun, author of American Islamophobia, wrote on Facebook:

Today’s ruling on the Muslim Ban was driven by the preposterous idea that one could assess the Executive Order by extracting it from the context it arose in and from the individual that masterminded it.

It wasn’t discriminatory, according to Judge Roberts, because it was facially neutral. Trump’s explicit naming of it as the “Muslim Ban” while campaigning and incessant anti-Muslim rhetoric after he won the presidency was immaterial although it was HIS executive order. …

Second, the initial rendition of the Ban, which specifically lists seven Muslim-majority countries and provides of religious exemptions (for non-Muslims) was ultimately irrelevant to assessing the constitutionality of the Order.

Third, the broader culture and context Trump has cultivated, which endorses explicit Islamophobia as legitimate discourse and policy, cannot reasonably be divorced from the spirit and mandate of the Muslim Ban.

Fourth, this Supreme Court’s recent decisions establish that religious discriminatory intent seems to only exist when the target are Christians.

Although the majority on the Supreme Court reject the idea that this Muslim Ban must be tied to Trump’s brazen rhetoric and this administration’s robust deployment of Islamophobia, History will see it otherwise – and remember June 26, 2018 as the date the Supreme Court of the U.S. upheld an executive’s desire to ban Muslims.

It may seem immaterial now to keep using the hashtag #NoMuslimBanEver, but as the favorite Martin Luther King Jr quote of nearly every social justice activist goes: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

So, I repeat, #NoMuslimBanEver.