Nowadays I work as a chaplain in Home Hospice – helping patients and their families voice their hopes and fears around the process of a life ending, bring forward the joys and sorrows of that life and the relationships in it, acknowledge and begin to process the grief-in-advance that may be present.

Hospice Chaplaincy As A UU-Pagan

It’s important work, and it may be that Unitarian Universalists are uniquely qualified to do it, or at least to be trained to do it. I’ve nothing against my Christian colleagues, some of whom are truly gifted chaplains, but I do keep noticing that their worldview sometimes gets in the way.

“What’s your religion?” is a fine, seemingly-inclusive question, until the Atheist patient bristles at it, or the long-lapsed Catholic feels shame before a clergyone. “Everybody believes in something” is certainly true – but many people’s beliefs don’t include “God” (or at least, the “God” of the particular chaplain’s understanding).

Many of the UUs I know have come to one religious tradition from another, knowing deeply that there can be more than one spiritual “truth” – and then we come together to worship with unanimity of purpose, but not unanimity of dogma.

Maybe a UU-Pagan chaplain is best placed to hear, “That’s just too much God-talk for me” and not feel personally shut down. Or maybe I’ve finally arrived at neutrality (which maybe I can do for a few hours at a time, but don’t bet on my having arrived there permanently).

Hospice chaplaincy is good work, and I’m grateful to be able to do it. I’m also learning a lot about how life ends, and how that process is for the people most closely involved. A preview for myself, of course, and also a way to understand the people in my life better (even though few of them have been through this process, even now).

The emotional and spiritual end-of-life process is so different from one patient to the next, one family to the next. (Identifying details changed to protect their privacy).

One patient feels bereft, and somewhat abandoned, because he has recently moved away from the friends who have been most important – and now it’s too far for any of them to visit, and he is too hard of hearing to talk with them by phone.

Another patient asked her friends and even her pastor to stop visiting weeks ago. She greeted me briefly: “You seem like a nice person, but I just don’t have the energy for another relationship; I hope you understand.” Then she closed her eyes and turned her head away – and her son escorted me out of the room.

One family sits around the patient’s bed, singing favorite songs – some from the hymnal, some quite bawdy (the oldest daughter looks askance at the chaplain, afraid of giving offense, then looks relieved when she sees I’m grinning at the lyrics).

Another family argues about whose turn it is to go sit with the old man, who is lonely and repetitive and smells bad because of his illness even though he had a bath this morning.

The Witch asks: is this what you want to be talking about? I reply that I’ve been afraid to talk about these things. She says I must.

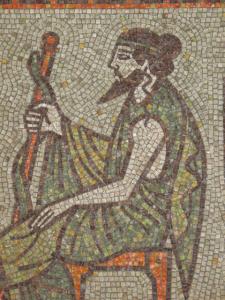

Asklepios and Nepenthe

Earlier this week I spent several hours in the company of Asklepios, Greek god of healing, and Nepenthe, a goddess named for the (probably fictional) drink of ‘forgetfulness of sorrow’ mentioned in Homer. During a rite-of-passage ritual, these two upheld my participation and lent me their strength and focus. Afterward I realized that both have been with me for weeks, in almost every hospice visit.

Asklepios started out as a demi-god, with mostly human characteristics, who became a great healer. Eventually he even tried to restore the dead to life, which angered Zeus so much that he killed him with a thunderbolt, after which Asklepios became a god.

As I visit patients, Asklepios sometimes seems to tend old spiritual wounds – disappointments and sorrows, broken relationships and regrets, painful incidents that have been long repressed but now reappear for healing in the last weeks of a person’s life.

In some families, He shows me that the patient may become a divine figure for the family after death – from ‘what would Grandma do?’ to insisting the deceased was perfect in every way (and stifling the stories in which they were not).

Once in awhile I watch as families invoke a modern equivalent of Asklepios to try to bring their dying patient back to life, even when that life seems to be burdensome to the patient, and even when the patient says they are done.

Nepenthe has less of a written history, but in some ways She is clearer to me because of that. Wikipedia talks about the fictional drink and its citations (all dependent upon Homer) in the works of Poe and other writers, all the way up to 20th-Century popular music. She began appearing in my dreams, bringing forgetfulness of some of the sorrows in my life, and talking about being ‘forgotten’ Herself.

When I’m with patients, She often helps me see that speaking about what troubles them can allow it to lift … and acknowledging the pain (physical or mental) can allow it to recede, to be forgotten.

The Witch asks me what I am not saying.

Sometimes I envy my patients – the ones who are dying in their own homes, surrounded by loving family members who speak fondly of good times shared and good deeds done, spouses who look at each other with such deep love.

Sometimes I recognize the irony of my warm relationship with a Goddess of Forgetfulness, as my own memory disappears down a rabbit-hole. Perhaps it would be better to work with a Deity in charge of tiny scraps of paper with incomprehensible notes.

You should go back to speak with Mnemosyne, says the Witch, and I see at once that this is so. How could I have forgotten the Goddess of Memory? The Witch asks me what I am so afraid of.

I fear the moments when my lapses of memory cause hurt to someone else. This has already happened to some of my friends, who have been patiently forgiving even when their feelings have been hurt. What will happen when I make that kind of mistake with a patient? or the patient’s family? What if it makes them angry with our whole agency?

I fear the moments when I run into someone in public who clearly recognizes me from this intimate work … and I clearly don’t recognize them at all.

Sometimes, too, I fear the moments when some medical professional half my age reads my forgetfulness as something to patronize, or takes it for the kind of dottiness that means I won’t want to (or be able to) make my own decisions.

For some of our patients, the worst part of dying is the loss of control before it happens. Needing help to get up from a chair is bad enough, but it’s worse when your caregiver says ‘just a minute’ and makes you wait half an hour. Needing pain medication is bad enough, but it’s worse when the choice comes down to ‘be in pain’ or ‘take a medication that makes you feel weird.’ Having no appetite is bad enough, but worse when your beloved family keeps begging you to take just one more bite.

Sometimes I fear becoming that patient, too.

The Witch reminds me that, by the time I arrive in Hospice for myself, everyone around me will have heard a lot about what I want — because I keep talking and teaching about it.

The Witch reminds me to remind you: Fill out your advance directive. Sign it before witnesses. Choose your health-care proxy. Tell them what you want, to the best of your knowledge now. Don’t leave those decisions to some well-meaning stranger who doesn’t know you at all.