In some Catholic media settings, there are people you’re advised not to talk to, or topics that you’re told in no uncertain terms not to write or speak about.

“The audience really doesn’t like this source because he/she is too liberal.”

“The last time we wrote about this, we got angry letters to the editor for weeks. Stay away from it.”

“Our listeners are complaining. Stop talking about racism already.”

On that last point, just ask Gloria Purvis, who paid the price for her outspokenness on racial justice issues by being fired late last year by the Eternal Word Television Network.

I’ve always been of the opinion that that kind of editorial self-censorship does no service to the Church. All that really does is to short-circuit the kind of engaging and faithful Catholic journalism that most audiences find compelling.

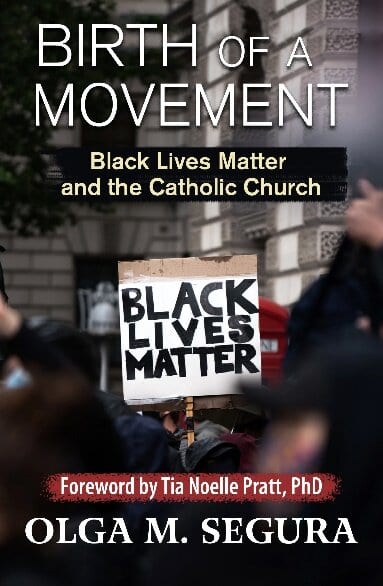

Thankfully, the Catholic journalist Olga M. Segura doesn’t appear to have had any of those editorial limitations in writing her new book, “Birth of a Movement: Black Lives Matter and The Catholic Church.”

The end result is a well-researched, well-written book that doesn’t hold back any punches and engages controversial ideas and proposed policy prescriptions in a forthright manner. Segura cites Black scholars and activists who are too often filtered out of the conversation in American Catholic media because of fears that their strong voices will rankle bishops, big-money donors, readers and listeners, a large number of whom are white and skew conservative in their politics.

Without a doubt, the book will reinforce negative opinions many of those Catholics already have about Black Lives Matter, both as an organization and a social movement. For more moderate readers, as well as progressive activists who may already have carried #BLM signs in the streets, “Birth of a Movement” provides enough intellectual food for fodder that the book should be read methodically over the course of a week, or two.

“The way Segura moves between the individual and organizational levels of analysis greatly benefits those who don’t do that in their own thinking but need to,” Tia Noelle Pratt, the religion socialist and Black Catholic scholar who curates The #BlackCatholics Syllabus, writes in the book’s foreword.

Black Lives Matter, the Movement

At the time of Pratt’s contribution, Kentucky’s attorney general had just announced there would be no criminal charges filed in direct connection to the death of Breonna Taylor, a young Black woman shot in her own home a year ago when Louisville police officers executed a “no-knock” search warrant to arrest her boyfriend on drug charges.

“It is for her and so many others, including ourselves, that we say Black Lives Matter,” Pratt writes.

The phrase “Black Lives Matter” is a self-evident truth, an innocuous enough observation – or at least it should be – that any Catholic or person of good will should have no problem embracing those three simple words as a fundamental truth, without any qualifiers. But in a country with deep racial fault lines dating back 400 years and an increasingly polarized political climate, BLM has been a lightning rod almost from the movement’s very beginning.

The criticisms I’ve seen over the years, from Catholics and others, have ranged from eye-rolls and dismissive responses that suggested activists were overstating the problem of racism in the United States, to condemnatory accusations today that Black Lives Matter champions anarchy, violence, communism, and seeks to destroy the family and Christianity.

Even against that heated backdrop, Segura presents Black Lives Matter in its complex ideological entirety, delving into subjects that overlap neatly with Catholic Social Teaching – at one point she describes BLM as “the secular version of Catholic social teaching” – but also engaging matters that objectively seem difficult, if not impossible, to square with some of the Church’s moral teachings, especially pertaining to sexual morality.

For example, Segura unflinchingly cites the work of the Black activist Angela Yvonne Davis, a Marxist and longtime member of Communist Party USA who the author says the nation’s Catholic bishops would be wise to engage and learn from.

“Davis encourages citizens to reject the evils of capitalism and, instead, uplift our communities over our individual selves,” Segura writes.

On capitalism, which she describes as racial capitalism, Segura argues that people of color like her – she was born in the Dominican Republic – “were never meant to succeed in this system.”

Segura is upfront about the Black Lives Matter movement’s opposition to capitalism because of what she describes as that system’s historical and continuing exploitation of people of color to benefit white people of European descent and the socio-economic system they created in North America that helps to reinforce the notion of whiteness as the normative default setting for American society, i.e. white supremacy.

Socialism and communism, Segura argues, “are more compatible with Christianity than capitalism. Both mimic Jesus’ commands: love your neighbor; dismantle oppressive institutions; give power to the weak.”

That claim, along with quoting Davis and utilizing the language of liberation theology throughout the book, will definitely anger conservatives and others – Catholic and otherwise – who place almost as much faith in free enterprise as they do in God. The book may also be used to bolster claims that Black Lives Matter is a Marxist-inspired movement aimed at overthrowing “the American way of life,” which can mean very different things to, say, white people in Orange County, California, and the Black community in Flint, Michigan.

More moderate readers may disagree with Segura’s statements about capitalism, arguing that the system can be reformed to make it easier for communities of color to access capital and build wealth, that money in and of itself is not a racist convention, and that, after all, we have Black middle class families, and the market economy has lifted untold millions, if not billions, of people out of poverty. Thorny questions still need to be answered, however, as to why Black people in the United States have more difficulty, with the way the country’s economic-political system is currently constructed, entering the middle class, getting credit to start businesses, and buying homes in white-majority neighborhoods, to name a few realities.

Black Lives Matter, both as an organization and a social movement, is all-embracing of those on the gender identity and sexual orientation spectrum. In her chapter on racial capitalism, Segura at one point writes of Clarissa Brooks, a “black, queer writer and activist” whom Segura credits for pushing her “to internalize the message that capitalism was violence.” Segura also writes that church leaders should incorporate the work of “Black, queer women” if they are serious about creating a church that vehemently condemns racism and white supremacy.

Issues of gender identity and sexual orientation are often a third rail in Catholic public discourse, electrocuting anybody who tries to seriously engage that tension between the Church’s teachings on sexual morality, the innate dignity of the human person, our growing understandings of human sexuality, and fostering a dialogue between people of good will who disagree on these subjects. See Father James Martin.

Defund -or Abolish – the Police?

That Catholic critics of BLM point to its embrace of the LGBTQ movement does not surprise me, nor their critical takes on BLM’s very critical view of the country’s law enforcement establishment.

Web pages for BLM and its individual chapters link to sites about “Defund the Police,” which last year became a political cudgel for conservative Republicans and President Donald Trump to wield against Joe Biden and the Democrats. While Biden and more centrist Democrats sought to dismiss “defund the police” as something silly or not serious, Segura puts it right out there in “Birth of a Movement” that policing as we know it needs to not just be reformed, but abolished.

“Policing enables the exploitation, torture, and slave labor of the prison system by violently harassing and targeting already marginalize communities, particularly Black women and men,” writes Segura, who later argues that policing was “born out of the same anti-Black violence” that allowed Americans to justify the violence of enslavement, from chattel slavery to the modern prison-industrial complex.

As do many issues in our country, views of policing and law enforcement tend to break down along racial lines. Police brutality and inexcusable acts of violence against Black people, even those incidents caught on tape, are often excused or dismissed away by white Americans, many of whom attack the unarmed Black victims as criminals or somehow deserving of being killed by uniformed law enforcement.

And even if you disagree with Segura and believe that policing as we know it can be reformed, you have to confront some difficult truths about the deep-rooted pathologies in the culture of law enforcement that encourages officers to avoid accountability, cover up for the worst people in the ranks, and act with impunity in the streets, sometimes firing non-lethal rounds into people’s homes during protests. I was a police reporter long enough for local daily newspapers to know that reforming law enforcement requires root-and-branch change, even radical alterations, not just tinkering on the margins. Whether that means serious reform or outright abolition, I’ll leave that to other people to decide.

In the end, “Birth of a Movement,” depending where you are on the political spectrum, may inform and educate you; perhaps the book will edify or motivate you; or Segura’s work may really anger you and confirm your suspicions about Black Lives Matter. Either way, BLM is the leading civil rights movement, not only in the United States, but in the world today, and Segura makes a good case that it has to be engaged if anyone is truly serious about racial reconciliation, justice and healing.

That includes the Catholic Church in the United States. Not all, but many, of its white bishops, priests and lay faithful are seemingly content to be second-guessing critics or passive observers of our ongoing national reckoning with racism. Just saying that the Church already has all the answers to racial justice in its body of social teachings is not enough. The work has to be put in, regardless of what the critics think.