Christmas is a holiday with numerous traditions and a very long history. Some of that history can be traced to the paganisms of antiquity (perhaps even more so than Halloween), and some of it also arose from Christian tradition.

It doesn’t matter where our holiday customs come from, but it’s fascinating (and fun) to trace their various origins. Some of them are only a few hundred years old or less, and some are literally thousands of years old. Decorating with holly doesn’t suddenly make one a Pagan, nor does using the word Christmas make one a Christian. Christmas is a confluence of religious traditions, capitalism, story telling, and the human need to simply connect with those we love. Christmas is more powerful because it reflects a wide range of influences.

What follows are twelve different holiday traditions (of course it had to be twelve, twelve days of Christmas and all that) and an outline of their various origins. At the end of each tradition I render a verdict on whether that tradition is Pagan, Christian, or Secular. It’s all in good fun, but the information is accurate. Happy Holidays!

Holly and Ivy: I’ll always associate holly and ivy together during the Holidays, no doubt due to the song The Holly and the Ivy. Holly remains a popular Christmas decoration with its distinctive green leaves and red berries, but sadly about the only time ivy turns up during the holidays is when someone is singing to the song I just mentioned. Decorating with holly (and ivy) is an ancient pagan tradition (1) and was used by the Romans to decorate at Saturnalia celebrations. Like most plants (or trees) on this list early Christians were well aware of the pagan origins of decorating with holly. Pope Gregory the Great even encouraged the continuation of some pagan traditions. In a letter written in 601 CE (Common Era) he wrote:

“The idol temples of that race should by no means be destroyed, but only the idols in them. Take holy water and sprinkle it in these shrines, build altars and place relics in them . . . When this people see that their shrines are not destroyed they shall be able to banish error from their hearts and be more ready to come to the places they are familiar with, but now recognizing and worshipping the true God . . . . .Thus while some outward rejoicings are preserved, they will be able more easily to share in inward rejoicings. It is doubtless impossible to cut everything at once from their stubborn minds . . . .”

As we shall see, Gregory’s advice was taken on more than one occasion when dealing with Midwinter traditions.

Verdict: Holly and Ivy are most certainly Pagan Traditions, but to be fair, if you are looking to decorate in December with greenery your choices are pretty limited.

Mistletoe: Mistletoe was a popular decoration at Roman winter festivals and is probably better known for killing Balder in Norse Mythology (darn Loki!) and as an alleged sacred plant of the Druids if Pliny the Elder is to be believed. (2) Ancient pagans most certainly decorated with it, but it didn’t become the kissing plant we are familiar with until centuries later. The “kissing bush” was first popularized in the late 18th Century and originally contained more than mistletoe.

Holly, evergreens, fruit, and mistletoe were often bunched together and then hung over doorways to instigate kissing. No one is exactly sure why mistletoe became my favorite doorway ornament, but by the middle of the 19th Century it was a popular custom. (3) Mistletoe, like holly, stays green and produces berries over the winter, making it a natural for Yuletide decoration.

Verdict: A little bit of Christian and Pagan. Pagans certainly decorated with it, as did later Christians, but it was Christians who began the kissing custom.

Christmas Tree: The Christmas Tree has a possibly long and tangled history. Ancient Romans and Greeks decorated their homes with evergreen branches and there’s even a Roman mosaic depicting Dionysus with what appears to be an early version of the Christmas Tree. Pagans certainly used evergreens, but pictures of Dionysus aside, no one is completely sure if they used entire trees. Pagans in what is now Poland used to hang evergreen branches from their ceilings and decorate them as well.

There are two early Christian traditions which seem to foreshadow the Yuletide tree. The first is the Paradise Tree, usually an evergreen tree decorated with apples, and used as a prop for Christian mystery (or miracle) plays. December 24 was the old feast day of Adam and Eve so they were often around in churches near Christmas. German families also used to build Christmas Pyramids or Lichstocks, which were wooden frames often decorated with evergreen branches, fruit, and gifts. (4) The first “Christmas Tree” dates back to the early 1520’s in Germany and spread from there, becoming popular in the United States and Britain during the Nineteenth Century. (5)

Verdict: Probably mostly Christian, but with a touch of Pagan on the side. I’d love to argue that Dionysus set up the first Christmas Tree but it doesn’t seem all that likely.

Poinsettia: The poinsettia was first introduced to the United States in 1825 by the then ambassador to Mexico Dr. Joel Roberts Poinsett (who was a bit of an amateur botanist). During the winter the leaves of the poinsettia plant turn bright red (and other colors) making it a natural for holiday decorating. The plant became associated with Christmas due to a few different Mexican folktales. One tale tells of a little girl who wanted to give a gift to the baby Jesus but could only find weeds to bring him, which miraculously changed into poinsettias. Another more logical tale (how does a Mexican child get to the baby Jesus?) tells of a young boy who brought weeds to a Christmas Eve mass as an offering, where they too turned into poinsettias. The Aztecs were well aware of the poinsettia, but apparently didn’t use them for any specific religious purpose. (6)

Verdict: Christian.

Yule Log: The custom of the Yule Log is first documented in Britain in the early 1600’s, where it was first called a “Christmas Log.” Later it was dubbed the Yule Log or sometimes the Christmas block. More than just a giant piece of wood, the Yule Log was part of a large procession before entering a home, ending with a round or four of drinks for everyone who delivered it safe and sound. Many Christmas revelers attached supernatural power to the Yule Log; its burning was said to keep a home safe from harm for the next year. (7) The Norse most likely burned large logs to ward off evil spirits near Midwinter, it’s possible that this tradition led to the development of the Yule Log centuries later. (8)

Verdict: The more I read about the Yule Log and it’s magickal powers, which we’ve just scratched the surface of here, the more I think it’s likely to be a Pagan survival.

Lights and Light: The lights we decorate our homes (and trees) with during the Holiday season have a long history. Ancient pagans lit bonfires and candles on the winter solstice and the holidays around it to celebrate the return of the light. (9) In Christianity holiday lights are represented by Jesus as “the light of the world” and the star above Bethlehem that guided the magi written about in the book of Matthew. Solar deities such as Sol Invictus were also celebrated at Midwinter adding to the solar imagery.

Verdict: Most definitely Pagan.

Gift Giving: For many folks (especially of the younger variety) the highlight of Christmas is the receiving of gifts. Christians often look to the magi (more famous as “The Three Wise Men”) as the originators of the custom, but pagans were doing it long before Jesus was born. The Romans exchanged gifts at during Saturnalia (a winter holiday lasting the week of December 17-23), including toys and edible treats. (10) For several centuries gifts were given not at Christmas or the Winter Solstice but on New Year’s Day. Queen Victoria didn’t start giving out Christmas presents until 1900, instead she followed the old custom of New Year’s gifts. (11) It’s taken several centuries to slot out the various customs we now associate with Christmas, New Year’s, and Halloween.

Verdict: The idea of gift-giving in early Winter is a Pagan one.

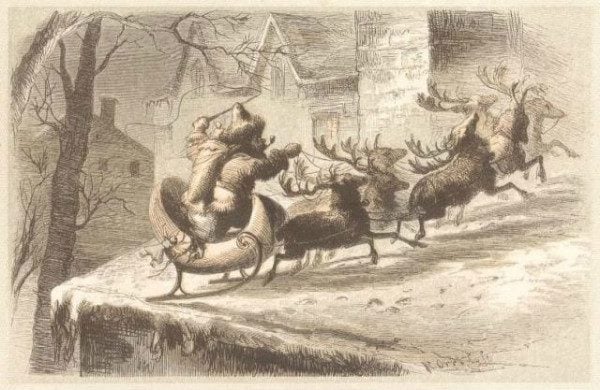

Santa Claus: The modern Santa Claus arose from a multitude of sources, both Christian and Pagan. Often ignored by scholars are the similarities between Dutch depictions of Saint Nicholas and and the Norse god Odin. In the Netherlands St. Nick’s first steed was not a reindeer but a horse, just like Odin. There’s most certainly a large dose of the Turkish St. Nicholas in our modern Santa Claus, most notably his generosity, and Nicholas’s popularity certainly helped carry the Santa Claus myth to lots of places around the world.

Santa Claus’s most famous appearance owes very little to Catholic or Norse myth, and is pure fairytale. Clement Moore’s A Vist From Saint Nicholas is a fanciful and secular take on the figure and has helped shape Santa myth for nearly two hundred years now.

Verdict: Santa contains both Pagan and Christian elements. His popularity has been helped in large part by the secular forces of capitalism too.

Stockings: According to legend Saint Nicholas once helped an old widower provide dowries for his three daughters by anonymously tossing three bags of coins into some stockings. (12) In popular myth, that story of Saint Nicholas is the reason why people hang stockings “by the chimney with care” today, but the inclusion of the stockings are most likely a late addition to the tale. The first (and in some places still the most common) receptacles for toys at Christmas were shoes. In many countries Saint Nicholas still puts presents in hopefully not smelly shoes. Clement Moore wrote about stockings in his poem guaranteeing their prominence in the United States and in some parts of Europe.

Verdict: Christian as far as I can tell.

Christmas Cards: The first Christmas Cards were produced in England in 1843, by the 1860’s the custom caught on and began to spread across the pond. The Christmas Card tradition usurped the previous tradition of New Year’s cards, a tradition that dates back to the 1400’s. Christmas Cards also ended up eclipsing the once popular tradition of sending out cards on Valentine’s Day to people other than one’s sweetheart. Early Christmas Cards often used Valentine’s Day imagery. (13) Most early Christmas Cards were completely secular in nature with very few religious depictions. (14)

Verdict: Secular, far more than religious.

The Date of Dec. 25: (Editor’s Note: This specific entry was massively updated in 2020.) Most Pagans and Witches will tell you that December 25 was chosen as the date for Christmas because of its proximity to various Pagan events. To back that up, many Pagans (and others) quote Scriptor Syrus whom many believed was writing in the Fourth Century of the Common Era:

“It was a custom of the pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that day.”

The problem here is that Syrus was not writing in the Fourth Century, he was writing in the Twelfth, nearly 800 years after the events he was chronicling. And if you’ve ever believed the above quote was from the Fourth Century, don’t feel bad, lots of talented scholars have too. In fact, the re-dating of this passage is a pretty recent development.

Syrus was correct that many Pagans did celebrate a birthday in honor of the sun on December 25, but that tradition only dates back to 274 CE. The first mention of Christmas being celebrated on Dec. 25 in written sources occurs about seventy-five years later in 354 CE and refers to a celebration in Rome in 336 CE. On the surface this appears to be an “open and shut” case, right? But today many scholars believe that the “birth of the sun” celebration on December 25 might be a re-action to Christian celebrations of Christmas, and those celebrations are older than generally thought.

Some of you are probably thinking, well what about Mitrha and all the other Pagan gods that were born on December 25? The idea that Mithra was born on December 25 is dismissed by scholars today, and the day most likely has no special significance in the cult of Mithra. It’s true that Brumalia, a holiday celebrated in honor of Dionysus and Saturn was celebrated December 25, but no one celebrated those two deities birthday on that date. Making things even more confusing, various groups celebrated the “Winter Solstice” from December 21-26 as no one was quite sure when exactly the shortest day of the year occurred. (15)

The “birth of the sun” celebration is worth circling back to as well. That holiday was created by the Roman Emperor Aurelian with the intention of creating something resembling a state religion. It was hoped that a general sun-god’s birthday would unite the Roman world, and it’s likely that he was trying to appeal to Christians as well as Pagans with the creation of his holiday.

One of the problems with Aurelian’s plan was that church leaders often actively despised Pagan customs and traditions. As Christmas became an established holiday in the Fourth Century the archbishop of Constantinople, Gregrory Nazianzen warned his flock in the year 380:

“Let us not put wreaths on our front doors, or assemble troupes of dancers, or decorate the streets. LEt us not feast the eyes, or mesmerize the sense of hearing, or make effeminate the sense fo smell, or prostitute the sense of taste, or gratify the sense of touch. These are ready paths to evil, and entrances of sin . . . .Let us not asses the bouquets of wines, the concotions of chefs, the great cost of perfumes. Let earth and sea not bring us as gifts the valued dung, for this is how I know to evaluate luxury . . . . But let us leave these things to the Greeks and to Greek pomp and festivals.”

The idea of appropriating a Pagan holiday for Christmas would have been blasphemous for many church leaders, which begs the question then, why December 25?

The answer probably lies in a strange idea from that era. It was believed that the births and deaths of great people always occurred on the same day. If you were born on February 12, you would probably die on February 12, though hopefully there would be many decades in between.

The gospels of the New Testament don’t offer much in the way of clues as to when Jesus was born, shepherds “watching their flocks by night” hints at the Spring, but it’s not definitive. However, the death of Jesus is an entirely different story, we know he was executed near the Jewish Passover. The idea of “death dates being the same as birth dates” was then amended slightly for Jesus. What if Jesus was conceived on March 25? That would put his birth on, you guessed it, December 25.

So is this the answer for the December 25 date? Possibly. Will we ever know for sure? No. Even if Christians didn’t place the birth of Jesus on December 25 because of Pagan influences, the rest of their holiday WAS (and IS) influenced by Paganism. The decorations, the celebrations, the carols, the presents, the drinking and merriment, all of those were things taken from the Pagans who celebrated Saturnalia and the January Kalends. Ultimately it doesn’t if the date of Christmas arose independently from the Pagan religions that surrounded it, all of its customs came from Pagan traditions.

In addition to things like the Saturnalia influencing Christmas there was also the Northern European Yule (which could mean “wheel” as in the wheel of the year, or perhaps “sacrifice” or “feast,” all worthy reasons for celebration) at the start of Winter with feasting, drinking, and general merry-making. Drinking might have been the most important of the observances. A poem about Harald Fairhair (the king who unified Norway) makes reference to the king intending to “drink jul (Yule)” even when out of Norway. Ritually passing the drinking horn was said to connect those drinking together to the gods themselves. Most likely there were also sacrifices to the gods and fertility rites, but information is sketchy and comes from mostly Christian sources. Eventually Yule became synonymous with Christmas and now the two words are used interchangeably. (16)

Verdict: We really aren’t sure. Maybe Christian? Certainly most of the trappings were (and have remained) Pagan.

The Birth Narratives of Jesus: For many people Christmas is about the birth of Jesus as related in the New Testament gospels of Matthew and Luke. While most historians think that Jesus was very much a real person, the majority of Bible scholars place little faith in the mythological narratives constructed by the authors of Luke and Matthew (even the authorship of those two books is up for debate). Matthew and Luke were written to express certain theological ideas. The first of those is that Jesus is the Jewish Messiah, as such both authors take pains to put Jesus into circumstances they believe were foretold in the Torah. This is why Jesus is born in Bethlehem, and why Luke’s author had to create a census that never happened to get him there. But there are other elements in the two birth stories of Jesus that reflect the pagan religions of the time.

Jesus was born in humble circumstances (at least in Luke) but was born due to the mingling of mortal and divine; Jesus had a god for a father and a mortal for a mother, just like most ancient pagan gods who walked the Earth. There’s nothing particularly Christian (or Jewish) about the magi (later they would become the Three Wise Men and be given names) either, and they could be a reference to the proto-monotheism of the Zoroastrian faith. When gods were born in ancient mythology their arrival was often marked by miraculous occurrences, these occurrences are mimicked in the New Testament with the Star of Bethlehem and angels heralding the birth of Jesus. This is not to suggest that the rest of the gospels depict Jesus as some sort of ancient pagan deity, they do not, but the birth stories in Matthew and Luke do, at least a little bit.

Verdict: A little bit of both?

Notes

I’ve read a great deal on Christmas the last twenty years, but for this article I consulted two books repeatedly in an effort to cite sources. There are a few items that are not sourced, you’ll have to trust that the information in my brain is correct.

1. The Stations of the Sun by Ronald Hutton, Oxford University Press, 1996. pages 34-35

2. Christmas a Candid History by Bruce David Forbes, University of California Press, 2007. page 120

3. Hutton page 37

4. Forbes page 48-50

5. Hutton page 114

6. Forbes 53-54

7. Hutton 39-40

8. Forbes page 12

9. Forbes page 8

10. Forbes page 8

11. Hutton page 116

12. Forbes page 70

13. Forbes pages 118-119

14. Hutton page 116

15. Hutton pages 1-4

16. Forbes pages 11-12