[While I have your attention, I’d like to inform you that my and Rua Lupa’s post archives from No Unsacred Place, our previous blogging endeavor, have been successfully ported over here to Paths Through the Forests. Once you’re done with this post we invite you to look at some of our earlier writings.]

Last week I talked about the importance of having nature nearby, even (and perhaps especially) in urban areas. To put it plainly, nature is good for us, and if we spend more time outdoors when we’re young, we’re more likely to keep up that habit as we get older. I’m definitely a product of that phenomenon; I spent many, many afternoons after school and long weekend and summer days playing in the yard and beyond. It gave me the opportunity to explore, turning over rocks and sticking my head into thickets of poplar trees to see who was hiding there.

Within those halcyon days filled with sun, rain, snow and wind, I experienced what Patrick Doran of the Nature Conservancy terms “consequential nature”:

[Consequential Strangers] argues that there are consequential strangers in everyone’s life that impact us in unknown ways. The authors refer to “the power of people that don’t seem to matter, but do…”.

For me, I think about the power of nature that doesn’t seem to matter, but does.

There exist those places, or combinations of places and times, that appear inconsequential but have a profound influence on who you are and how you experience the world.

Doran talks about some specific experiences he had as a child that, at the time, probably didn’t seem particularly significant–his first sighting of a tufted titmouse, or his first great blue heron. For me, it was laying on a bed of moss on the north side of my childhood home in the shade of a juniper bush. There’s nothing immediately profound about running your fingers over the soft green tendrils or moss, or pulling up the edge of the “carpet” to see the dirt underneath, but I still remember being there, with the smell of rain and earth and green growing things and the dim sunlight filtered through clouds creating faint, dull-edged shadows on the ground. A small moment, but to this day I have a deep and abiding fondness for moss and conifers and rich earth in the rain.

As children, we are tiny little sponges running around on two feet, soaking up as much information and experience as we can in a world still new to us. If we’re lucky, we retain that curiosity and receptiveness to the world and our neighbors within it as we grow older. Consequential nature is fuel for that drive. It’s not only the big, deep, rites of passage that keep us alive; in fact, some of them can be quite draining. Instead, it’s the little doses of wonder and awe that gently remind us to look outward, that we’re not alone, even if our lives are otherwise full of challenges–these quiet moments of connection are taps on the shoulder instead of a smack to the back of the head that can constitute a “profound experience”. And the effects of these often brief experiences may last very long indeed, sometimes for the rest of our lives.

As children, we are tiny little sponges running around on two feet, soaking up as much information and experience as we can in a world still new to us. If we’re lucky, we retain that curiosity and receptiveness to the world and our neighbors within it as we grow older. Consequential nature is fuel for that drive. It’s not only the big, deep, rites of passage that keep us alive; in fact, some of them can be quite draining. Instead, it’s the little doses of wonder and awe that gently remind us to look outward, that we’re not alone, even if our lives are otherwise full of challenges–these quiet moments of connection are taps on the shoulder instead of a smack to the back of the head that can constitute a “profound experience”. And the effects of these often brief experiences may last very long indeed, sometimes for the rest of our lives.

This is part of the tragedy of Richard Louv’s Nature Deficit Disorder. As children spend more and more time indoors with television, computers, video games and other passive entertainment, they have fewer opportunities to experience consequential nature. A tree made of pixels in a MMO just doesn’t cut it; research shows that even the most realistic digital tree doesn’t have the same effects as looking at the real deal. There’s a big difference between the sharply focused and all-consuming attention needed for a video game, and the soft fascination that provides a much-needed respite from the over-stimulation we are too often subjected to on a daily basis. If we’re too busy putting all of our attention directly in front of us, there’s no opportunity to relax our guard and allow the mutual gentle interplay between us and our environment that fosters consequential nature, among other restorative benefits.

All is not lost, however. I specialize in green urban living these days; getting my wild nature on when surrounded by noise and development and harsh concrete lines is challenging at times, but it’s made me shake off my complacency and seek solutions. As a woman in my mid-thirties, I can still access that sense of adventure and discovery I had as a child; in fact, my path as a pagan has largely been a quest to reclaim that sacred, primal connection to the world. We can still, as adults, experience consequential nature, even those of us who never really had much safe and unfettered outdoor time growing up. All it may take is that one little bird in a tree, or a flash of red as a fox darts through a city back yard, or the moment of discovering a new wildflower in a park. Three are countless moments in nature; some are bound to stay with us, even if they have to chip through rather jaded shells to really get to us.

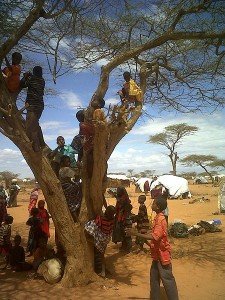

And while I don’t have children of my own, I encourage parents and other caretakers to get the little ones (and not so little ones) outside more. Since they’re still learning about the world, they more than anyone else deserve that rich landscape full of potential discoveries; this is their time to be soaking it all up as quickly as they can, and we owe it to them to give them as many opportunities as possible. I know it’s sometimes easier said than done; if I had kids in this tiny apartment with no yard, I’d have to take them several blocks away to the nearest park to find a place that wasn’t someone else’s lawn they could play in (though our walk over could be similarly full of discoveries). And it takes time to make time, as it were; if you’re already feeling overburdened with work and housekeeping and bills and other such things, going to the park for an hour may seem like more than you could possibly offer.

But do the best you can, both for the kids, and for yourself. There’s a lot to be gained; I agree with Doran when he says “I want to make sure that opportunities to explore the natural world are available to all people to learn these simple life lessons – observation, reflection, wonder, patience”. Nature is a lifelong teacher, and we all deserve a place in its school no matter who we are. The lessons may be brief and seemingly inconsequential, but what we get from them is priceless beyond compare.