Those are just a few of the comparisons that observers are drawing about Donald Trump.

First, the Billy Sunday analogy (shameless self-promotion alert):

For born-again Protestants, a personal encounter with God is essential to faith. Having “Jesus in my heart” is one way to put this. And such an emphasis on experience has meant that for evangelicals the structures or hierarchies that have typically defined and regulated Christianity – clergy, creeds, liturgy – are impositions that come between a believer and God. Taken to extremes, of course, this impulse leaves evangelicals without any institutions or organizations (or even a Bible). So it has rarely been taken to its logical conclusion, which is an average evangelical at home, alone which Jesus in her heart. But such an understanding of authentic faith has left evangelicals with a deep distrust of authorities who come between them and what they believe is genuine.

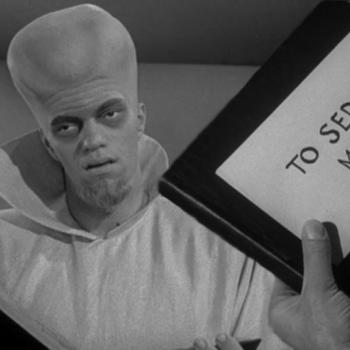

George Whitefield, the evangelist who put “great” in the First Great Awakening (circa 1740), was one of the first to tap the significance of personal experience. In his 1740 sermon, “The Kingdom of God,” he warned against identifying Christianity with the institutional church. “True and undefiled religion, doth not consist in being of this or that particular sect or communion.” If someone said to Whitefield he belonged to a church where they worshiped “in the same way” his parents did, the evangelist concluded that such a nominal Christian had placed the kingdom of God in “that in which does not consist.” Charles Finney, the celebrity evangelist of the Second Great Awakening (1820s) took the personal nature of Christianity and applied it in a way that undercut the authority of denominational structures. Of the highest body among American Presbyterians, Finney wrote, “No doubt there is a jubilee in hell every year about the time of meeting of the General Assembly.” Billy Sunday, another celebrity evangelist in the early twentieth century showed what evangelical attitudes to religious experience could mean for theology or formal study of religious truth. He boasted that he did “not know any more about theology than a jack rabbit does about ping pong.” But as long as he had a conversion experience he was qualified to preach.

H. L. Mencken, who covered some of Sunday’s exploits, put his finger on the appeal of evangelicalism and traced it directly to the anti-institutional, informal character of its devotion:

Even setting aside his painstaking avoidance of anything suggesting clerical garb and his indulgence in obviously unclerical gyration on his sacred stump, he comes down so palpably to the level of his audience, both in the matter and the manner of his discourse, that he quickly disarms the old suspicion of the holy clerk and gets the discussion going on the familiar and easy terms of a debate in a barroom. The raciness of his slang is not the whole story by any means; his attitude of mind lies behind it, and is more important. . . . It is marked, above all, by a contemptuous disregard of the theoretical and mystifying; an angry casting aside of what may be called the ecclesiastical mask, an eagerness to reduce all the abstrusities of Christian theology to a few and simple and (to the ingenuous) self-evident propositions, a violent determination to make of religion a practical, an imminent, an everyday concern.

Donald Trump is the Billy Sunday of Republican politics.

Then the likeness of Joel Osteen:

When pressed to explain how, exactly, he plans to navigate a rather complicated legal and political terrain to accomplish this, Trump doesn’t get any more specific. “The best people are going to fix the bad things,” we’re told. Don’t worry about the details.

As a theologian, Osteen is remarkably similar. Osteen is, by his own admission, not a doctrinal policy wonk. Rather, he sees arguing over the more minute details of Christian theology—details like, you know, the nature of Christ—as a hindrance to his simple message of “We’re going to fix all the bad things in your life.”

Much like Trump, when confronted with Biblical teachings that effectively say, “Well, actually, according to the Bible, fixing bad things is a bit more complicated than just becoming bolder and more confident,” Osteen stares blankly for a moment, then responds by writing another book promising you can make yourself great again simply by declaring that you’re great again—don’t worry about the particulars.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the cuddly soft preacher has found a bit of a kindred spirit in the rather prickly politician who vows to make Mexico pay for an even bigger wall every time our neighbors to the south refuse to pick up the tab. After all, the substance of Osteen’s preaching is essentially “We’re going to build you a wall of victory. The Lord is going to pay for it. And if God hasn’t agreed to it yet, then you clearly need to make bolder demands.”

What does it say that Calvinists and Lutherans see these similarities, but born-again Protestants don’t?