Massimo Faggioli, who teaches theology at Villanova, is always provocative even if you don’t agree. His analysis of the 11-page document by Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò about Cardinal Theodore McCarrick has several points worth considering.

One is this:

The political crisis. The rift within U.S. Catholicism, and between traditionalist Catholics and Francis, cannot be understood apart from the political polarization of America. The first phase of the problem was the growing identification of the U.S. bishops with the Republican Party, largely because of a few social issues. As the Republican Party has been radicalized in the past decade, so have more than a few bishops. During the same period, some prominent conservative intellectuals have embraced Catholicism for reasons that seem purely political. This is not a new phenomenon. It has much in common with Charles Maurras’ Action Française, a nationalist movement condemned by Pius XI in 1926. Maurras had no time for the Gospel but saw Catholicism as a useful tool for the creation of an antidemocratic social order. The new enthusiasm for an older version of Catholicism on the part of conservative intellectuals with no interest in theology also mirrors the rise of Ultramontanism in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Jesuit John O’Malley’s latest book on the theological movements that set the stage for Vatican I helps us see the many similarities between nineteenth-century Ultramontanism and early-twenty-first-century traditionalist Catholic Americanism. In both movements, the game is played mostly by journalists and other lay intellectuals whose understanding of the church is essentially political rather than spiritual. They celebrate the church as an institution that can withstand modernity, and especially the modern state. They have little or no interest in ecclesiology or sacramental theology—or anything else that cannot be easily weaponized against their political enemies.

The arresting claim here concerns the appeal of Roman Catholicism to political conservatives in the United States which goes back to the days of Phyllis Schlafly and William F. Buckley, Jr., though those figures grew up in the church. For some Protestants who convert to Roman Catholicism, the Vatican, the papacy, and the curia represent speed bumps on the road of modernity. As Buckley put it, ” A conservative is someone who stands athwart history, yelling Stop!” Where Faggioli might receive some push back is that his own appreciation of Pope Francis suffers some from the current papacy’s own political sermonizing about markets and the environment. If Francis only explained doctrine and talked up the sacraments, then Faggioli would be on firmer ice in criticizing U.S. conservatives.

Another point is this:

The geopolitical crisis. The Catholic media outlets that have been an integral part of the Viganò operation want to recapture Rome but have little knowledge of Rome or, for that matter, the global church. For them, the whole Catholic Church is the American Catholic Church writ large. Philadelphia is not the new Avignon, but the United States resembles what France was for Catholicism in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Great Western Schism resulted in part from a contest for leadership of Christian Europe between the papacy and the French monarchy. There is now a tacit contest for moral leadership between the world’s last superpower and the Vatican. This is a fracture within U.S. Catholicism, but also a fracture in the global church. It is worth noting that Latin American and European bishops’ conferences have publicly supported Francis since Viganò’s letter appeared, while there has been a shocking silence on the part of most U.S. cardinals and bishops. Some conservative U.S. bishops have vouched for Viganò’s integrity, and a few Francis appointees mentioned in the letter have come to the pope’s defense, but most U.S. bishops have kept their own counsel. Their failure to support Francis can be read as a sign of their desire to have answers from Rome about McCarrick, but it can also be understood as their attempt to recover their credibility by signaling their distance from a pope that the powerful Catholic right never really accepted. It isn’t clear how the relationship between these U.S. bishops and the pope will be repaired. The bishops’ synod on young people beginning next month in Rome is technically an “ordinary synod,” but, because of its timing, it is likely to be an extraordinary moment in the life of this fractured church.

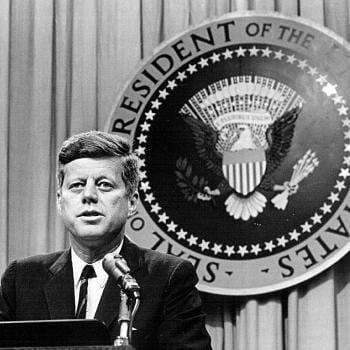

The comparison of 21st-century USA to 14th-century France is intriguing. Because so much of Roman Catholic history is bound up with Europe, U.S. Roman Catholics have had an inferiority complex, an sensibility compounded by the American church being an immigrant communion all the way down to World War II. But when American Roman Catholics left the ghetto for the lush lawns of the suburbs, the United States was also emerging as the leader of the “free world.” It couldn’t help but capture the Vatican’s attention that in 1961 a Roman Catholic became POTUS and the leader of the free world to boot. American dominance in world affairs throughout the Cold War and down to today has meant that Vatican officials have had to take the United States seriously in ways that previous popes, who worried about European monarchs and elites, did not.

The question that Faggioli does not answer is whether the U.S. bishops actually think they have the kind of power in global Roman Catholicism that the French did on the eve of the Great Schism. From this Protestants’ perspective, the German bishops seem to be a lot more assertive than their American counterparts.