To join the discussion about Quiet, or to buy a copy, go here.

I am also an elected official.

Many people assume that this makes me a walking, breathing contradiction in terms, an oxymoron, a rarest of the rare. However, they are wrong about this. Most of the politicians I know — and I know a lot of them — are introverts.

I’ve only known a few true extroverts who actually managed to make it into office, and they usually drive the rest of us crazy with their other-the-top, always-on, go-go-going. While extreme shyness would certainly be a problem for a politician, introversion, with its ability to focus, reflect and think things through, is, in fact, a huge advantage.

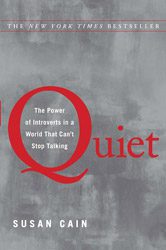

Susan Cain’s excellent book, Quiet, describes introverts quite well. It talks about the need introverts have to spend time alone, the powers of reflection, concentration and self-direction that are such a part of the introverted personality. In an earlier time, this was called “reserve;” as in “She’s not shy. She’s reserved.”

That’s what the school principal told my mother about me when I was in first grade. Mama commented that I was shy, and the principal corrected her with the astute assessment, “She’s not shy. She’s reserved.”

Personally, I like the word “reserved” better than introvert for the simple reasons that it’s both less clinical and more accurate. As Ms Cain describes, reserved people tend to think things through before they leap. They are prone to analyze and consider a move before they make it.

While the world needs people who will jump right in there when the occasion calls for it, it also needs more reflective and deliberate thinkers working alongside them. The excesses of either personality type can be destructive if they are allowed to run unchecked. They need the balance of association with the other personality type.

As with so much of what works with people, our personalities perform best in tandem with one another. The hard-charging extrovert will drive you right over a cliff if there isn’t someone sitting beside them with a map to find the way.

Unfortunately, as Ms Cain notes, American society is wired for extroverts. This can be downright punishing for young children in our schools. I suffered with it a bit when I was little, but I grew up in a much less chaotic time. One of my own children — who had inherited a good dose of his mother’s reserve — experienced public school as an isolating and utterly miserable box. I remember at the time thinking that our schools were designed for only a certain type of child and that all other children were judged defective to the extent that they failed to be that one type of child.

I took my child out of this environment. My only regret is that I ever put him there in the first place.

According to Ms Cain, many reserved people are forced to struggle to imitate their extroverted colleagues, even after they become adults. Her descriptions of life inside certain corporate environments explains at least in part why I knew instinctively that the corporate world was not the place for me.

Quiet is a good read and a needed book. The author makes the point that many of the tragedies of American life, including the economic debacle of 2008, are at least in part a result of the unbalanced emphasis we place on extroversion. Human beings were made from our beginning to work together in community. Our various parts fit together to create a whole that is civilization.

The author implies, and I agree, that our society would benefit from acknowledging the value that introverted people bring to any endeavor.

I highly recommend Quiet. It raises important points. It also is a necessary read for teachers, parents, and administrators who must learn to bring the best out in their children, students and employees who are “reserved.”