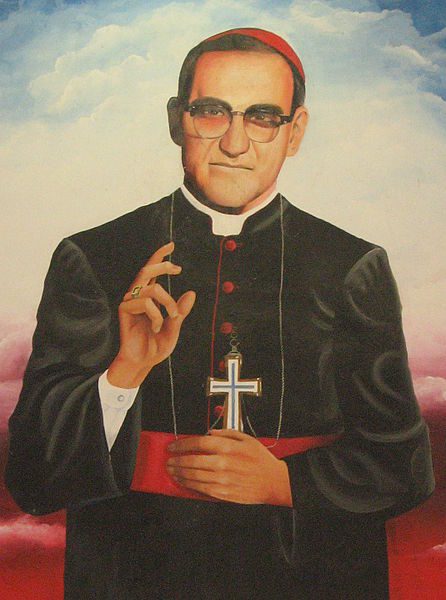

Archbishop Oscar Romero was murdered in 1980 by a right wing death squad for the crime of advocating for the poor people of El Salvador who were being murdered, tortured and disappeared in great numbers. Whole villages were slaughtered.

Most of the other priests and bishops stood by while all this happened. The pope himself failed.

The same Holy Spirit that moved Oscar Romero to speak out to such great peril to himself also motivated a few other priests and nuns. Quite a number of them were also murdered. Nuns and lay missionaries were raped, tortured and murdered for the “crime” of educating and helping the poor.

Oscar Romero will be canonized a saint this weekend. I hope that the day will come when the nuns who were raped and murdered as well as the other priests who stood for Christ crucified when He was suffering dying in the guise of the poor people of El Salvador.

Jesus was rather explicit about this: If you have done it to the least of these, you have done it to Me.

When you do this, when you truly follow Christ, you will be persecuted.

From NPR:

This Sunday, 38 years after his assassination, Romero will be canonized as a Catholic saint. Known to his followers as Monseñor (Monsignor), Romero was a champion of human rights at a time when El Salvador was on the brink of civil war. His tireless fight for civil rights ranks him among figures like Martin Luther King Jr. His devout following filled San Salvador’s towering cathedral each Mass.

“It was packed,” says Octavio Duran, a Franciscan brother who started working with Romero as a 21-year-old seminarian. “People were standing, people were sweating. I remember when Monseñor Romero was making his entrance, people clapping.”

Romero’s voice echoed above the violence that engulfed his country.

“At a time of so much confusion and anguish,” Romero said in his homily on Feb. 10, 1980, “I want to be a messenger of hope. In the midst of tragedy and bloodshed, there is hope.”

Leftist demonstrators flee after Salvadoran National Guard troops fire into a crowd of protesters on the steps of the San Salvador Cathedral in May 1979.

Tony Comiti/Sygma via Getty Images

A bus burns in the streets of San Salvador on May 15, 1979, after it was set on fire by leftist demonstrators.

Hamilton/Associated Press

At that time, “Hope was like water in the desert,” Duran says. “It was scary to live in those days.”

In the late 1970s, civil war loomed. Decades of government oppression sparked massive protests. Peasant workers united in the countryside, demanding basic rights. Popular opposition groups and teachers’ unions called for wealth distribution, while leftist guerrillas took up arms against the military and government elites.

In rural Catholic churches, some priests and nuns supported the peaceful cause on behalf of the poor. But they were up against El Salvador’s corrupt oligarchy. The country’s so-called “Fourteen Families,” who controlled most of the land and wealth, accused the priests and peasants of a communist uprising.

The Salvadoran National Guard roamed streets, searching for subversives. Priests were expelled from the country, beaten and imprisoned. Security forces burned villages and committed rape. The National Guard arrested family members, who never returned home again.

El Salvador’s brutal military regime — supported by the United States — kidnapped, tortured and killed civilians, many of them among the poorest.

The “voice of the voiceless”

“These were atrocities towards innocent people, young people, even children,” says Morales Tijerino, who is an interpreter, translator and human rights activist. She says Romero defended the most vulnerable.