Adam and Eve justified eating the forbidden fruit by blaming each other, blaming the serpent, and blaming God. As natural as breathing air, we human beings draw an imaginary line between good and evil. Then we place ourselves on the good side of the line. Sometimes we place someone else on the evil side of that line. We blame the evil person. We verbally curse or physically punish that person. And we do so in the name of the good. This mechanism has a name: the visible scapegoat.

Adam and Eve justified eating the forbidden fruit by blaming each other, blaming the serpent, and blaming God. As natural as breathing air, we human beings draw an imaginary line between good and evil. Then we place ourselves on the good side of the line. Sometimes we place someone else on the evil side of that line. We blame the evil person. We verbally curse or physically punish that person. And we do so in the name of the good. This mechanism has a name: the visible scapegoat.

Oh no! Not sin again!

Most of us just do not want to talk about sin. I get that. But, sin-talk can still be very illuminating. Sin-talk shines a light into the dark corners of our psyche and into the shadows of our social bonds. In what follows we will track a paradox of sin, namely, we engage in evil when in the process of purifying ourselves. Self-purification can become deadly to those we scapegoat.

In a twisted and delusional way, we ask the scapegoat to purify us. After all, we want to be on the good side of that line we draw. But, does this really work? Can we fool God?

There are two kinds of scapegoats: the visible and the invisible. This post is the third in a series: 1. Sin? Really? 2. Sin and Self-Justification. 3. Sin and the Visible Scapegoat. This will be followed by a post on the Invisible Scapegoat and then, finally, a post titled, “Sin Boldly!” Stay tuned.

Purification? How does that work?

We scapegoat in order to purify ourselves as an individual or as a community. Each human community wants to see itself without blemish, stain, sin, evil, disease, or self-destructive violence. In ancient Israel, the scapegoat bore the sins of Israel away on the Day of Atonement. Leviticus 16:16a, 21: “Thus he shall make atonement for the sanctuary, because of the uncleanness of the people of Israel….Then Aaron shall lay both his hands on the head of the live goat, and confess over it all the iniquities of the people of Israel, and all their transgressions, all their sins, putting them on the head of the goat, and sending it away into the wilderness by means of someone designated for the task.” By cursing the living goat and sending the cursed animal into the wilderness, the “uncleanness of the people of Israel” could be atoned for. Once the scapegoat was gone, then the remaining community could deem itself pure.

Jews today remember this as Yom Kippur, described beautifully by Delisa Hargrove.

Christians are not asking this ancient scapegoat ritual to provide a means of atonement for us today. In the wake of Jesus Christ’s atoning work, no such ritual is needed today. Nevertheless, this ancient Levitical ritual provides a map of the human psyche. We are pressed by inner forces to pursue self-purification. Hidden in the cracks and crannies of our consciousness the scapegoat stands ready to purify us through suffering our condemnation. We are blind to the evil that scapegoating reaps because we cover it over with the self-justification lie. (Scapegoat painting by Holman Hunt)

Is the self-justification lie a form of denial? You betcha! At least one contemporary psychologist, Eric Brahm, defines scapegoating as “a psychological defense mechanism of denial through projecting responsibility and blame on others.” From religious ritual to psychological mechanism. Scapegoating is a form of self-justification and even self-purification for individuals, to be sure; but also for sports fans, ethnic traditions, races, nations, and, most importantly, armies.

What about families? Yes, indeed. “Commonplace in toxic families, scapegoats are children blamed for all the problems in dysfunctional households,” observes Nadra Nittle. Other members of the family feel purified when the dysfunction of the family as a whole is displaced on to the scapegoated individual. We can only weep at the helplessness of the child victim of the scapegoat mechanism.

Must the scapegoated person or group be innocent? One sociologist thinks so. Ashley Crossman says “scapegoating refers to a process by which a person or group is unfairly blamed for something they didn’t do.” Patheos columnist Chuck McKnight avers that “It isn’t scapegoating if you’re guilty.” I disagree. In fact, it does not matter whether the scapegoat is guilty or innocent of the charge. What we are looking at here is how the scapegoat mechanism works in us, the sinners. We engage in self-purification and self-justification regardless of whether the scapegoat is innocent or rightly charged. More. When it comes to the invisible scapegoat in a future blog post, I’ll demonstrate how the scapegoaters ascribe innocence to the invisible scapegoat.

In ancient Israel purification via scapegoat was visible, public, transparent. In our own day, purification via scapegoat is hidden, disguised, covered over by bravado, lies, and hypocrisy. In our day, purification via scapegoat goes on perpetually, ever seeking newer scapegoats to replace the discarded ones (Peters, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society, 1993). Now, just what am I talking about here? Let me start by referring to one of my favorite scapegoat theorists, René Girard. (Painting, “Scapegoat,” Holman Hunt)

Who is our visible scapegoat?

If we are going to turn the light on to make what is dark visible, let’s think of the scapegoat as a victim. The victimized scapegoat gets sacrificed for our own self-purification. How does this work?

Mimetic desire–desiring what others desire and not desiring a basic need–leads to conflict is groups, communities, nations, or between nations. When all parties desire the same object, a crisis is precipitated. War may even commence. The crisis is resolved when a scapegoat is designated. The scapegoat is then marginalized, sacrificed, or destroyed. Peace returns. Until the next crisis precipitated by the next mimetic rivalry, that is. According to Girardian theory, the scapegoat creates or maintains a peaceful community. This is a peace built on violence, to be sure. Now, with this background, let’s turn specifically to the scapegoat.

The term scapegoat, René Girard says, “designates (1) the victim of the ritual described in Leviticus; (2) all the victims of similar rituals that exist in archaic societies and that are called rituals of expulsion, and finally; (3) all the phenomena of non-ritualized collective transference that we observe or believe we observe around us….We cry ‘scapegoat’ to stigmatize all the phenomena of discrimination–political, ethnic, religious, social, racial, etc.–that we observe about us. We are right. We easily see now that scapegoats multiply wherever human groups seek to lock themselves into a given identity–communal, local, national, ideological, racial, religious, and so on” (Girard R. , 2001, p. 160).

Nations scapegoat foreign enemies. Employees scapegoat their boss. Bigots scapegoat immigrants or people of color. Republicans scapegoat Democrats. And vice versa. The scapegoats are very visible. What is invisible, is the mechanism of self-purification employed by the scapegoaters. Employing the mechanism of self-purification is commonly known as sin.

Here is one example. Former U.S. President Donald Trump cursed selected foreigners. The context was the president’s policy to reduce if not eliminate immigration to the U.S. from specific locations: Haiti, El Salvador, and Africa. He rhetorically asked: “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?” (Dawsey) Identifying the visible scapegoat—people in these selected foreign countries–with excrement is a form of public cursing that justifies purifying our own country from contamination by outsiders. It matters zilch whether immigrants from these countries are saints or sinners. What matters here is exposing how the mechanism of self-purification via scapegoating works.

Here is a second example. 2016 U.S. presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, described the supporters of her opponent as deplorable. Her words: half of Donald Trump’s supporters belong in a “basket of deplorables,” because they hold “racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic” views (Reilly, 2016). Clinton drew a line between good and evil. She placed her opponent on the evil side along with his supporters. We know these people are evil because they are racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, and Islamophobic. Right? Clinton self-justifies by scapegoating her opponents. It matters zilch whether the accusations against the scapegoat are true or false. The act of accusing alone functions invisibly to purify the scapegoater.

To Malign is to Bind: the Visible Scapegoat

Drawing a line between good and evil followed by placing a scapegoat on the evil side is the blueprint followed by national leaders when leading us to war. The enemy is vividly portrayed as unclean, immoral, threatening, and weak. We would do the world a favor by calling forth all our military might to rid humanity of this particular enemy. When we come to believe such political rhetoric, the entire society embraces the lie that we can self-purify by perpetrating violence in a foreign country.

This self-purifying rhetoric I call, “cursing” (Peters, Sin Boldly!, 2015, pp. 227-235). When cursing, we publicly accuse the visible scapegoat of being weak, sinful, or tyrannical. Liberal and progressive Christians know the routine of cursing evangelical Christians well. “They [progressive Christians] have banished all who disagree from their midst,” observes Jeff Hood in a Patheos post. They term them, “backward,” “close-minded,” “uneducated,” or, worst of all, “conservative.” In turn, evangelicals don’t hesitate to question whether liberal or progressive Christians are even Christian at all. Christians curse just as everyone else curses. This is true despite the fact, observes Danielle Kingstrom, that “Jesus showed that lines don’t exist; that your neighbor is yourself; and we are all one.”

Cursing discourse divides and separates us, to be sure. It even readies us for war. World War One provides an example of cursing and counter-cursing. Each side described itself as godly and moral but described the other as ungodly and immoral. From one side we heard: “It is Germany’s task, as God’s instrument, to execute a world-historical divine judgment on our enemies, as they represent the spirit of darkness, the deadly enemy of the Kingdom of God” (Schwager, 1988). From the other side we heard: Germany’s war aims are “anti-Christian” and “the lie is a constituent element at the innermost core of the German person” (Schwager, 1988). A nation commits itself to war only when pursuing what is just or good. War becomes justified in the cursing of the enemy, the scapegoat. To malign is to bind.

What we have just described here is the visible scapegoat. To be sure, the mechanism of self-purification whereby we lie to ourselves in order to justify committing violence may lurk in the shadows, only partially visible. But, the victim of our cursing and our bombing is quite visible. In a future Paheos column I will attempt to expose a second form of scapegoat, the invisible scapegoat.

Deforming the Soul via the Self-Purification Lie

Scapegoating deforms the soul. Why? Because when scapegoating the soul forms itself around a lie, a lie that feeds and grows off violence perpetrated against those whom we victimize. Here is the key lie: we tell ourselves that we are good and that aliens at home or enemies abroad are evil. And through this lie we engage in self-justification, self-purification. The lie might accomplish its task through gossip alone. But the delusion can in some cases lead to the expulsion of the alien or the death of the enemy.

“The language of warfare, spiritual and cultural, is toxic and destructive,” observes C. Don Jones. “The rallying spirit is not the Spirit of God. It displays the wrong attitude toward the rest of the world.” But, alas, we know from experience that it’s so self-justifying and so self-affirming to join the rally cry! Our identity becomes clear when we stand up for justice against someone recognized by our in-group as the enemy. Scapegoating feels so good! But, here’s the catch: declaring someone to be an enemy in itself deforms our own soul.

Is there a better way? Yes. According to Lindsey Paris-Lopez, who applies Girardian theory to scapegoating. We are admonished to love rather than curse or separate ourselves from our enemies.

Does this apply to atheists too? Yes, according to Patheos columnist Duncan Edward Pile. Pile avoids declaring war on atheists. Pile avoids drawing a line between good and evil; and he avoids placing atheists on the evil side. He quips, “It is better to live in honest unbelief , than dishonest belief.” He ascribes to his atheist friends a good trait, namely, honesty. Pile avoids deforming his own soul; he refuse to turn atheists into a visible scapegoat.

To abide in Christ, says popular preacher Nadia Bolz Weber, makes those we have placed on the evil side of the lines lovable. “Abiding in Christ means loving the other precisely when they are least lovable.” To abide in Christ is to love rather than scapegoat. In fact, to abide in Christ prompts us to identify with scapegoats everywhere. “Progressive Christianity, adds Roger Wolsey, “shifts the focus from avoiding sin to focusing on love.”

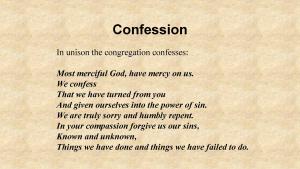

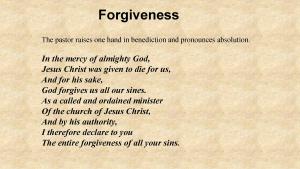

Is there a better way to purify the human soul than self-justification and scapegoating? Yes, indeed. It’s called confession and absolution.

Confession and Absolution

Jesus Christ is the scapegoat–the final scapegoat!–who purifies the sinful person and sinful community. “The Second Person of the Trinity took into Himself the sins and the griefs of the entire world and bore the suffering that attends them in order to redeem us,” Gene Veith makes clear. When we allow Jesus Christ to be our scapegoat, we have no need to make any other victim our scapegoat. In principle, all other potential scapegoats get liberated from our sinning.

Keith Giles adds a relevant point: in Jesus Christ the human race is united. “Therefore, there is truly no such thing as “them” anymore. There is now only one eternal “us” that finds itself forever in union with God through Christ.” Without a “them,” we have no one to scapegoat.

All those potential victims or our future scapegoating just might be grateful, whether they know it or not.

▀

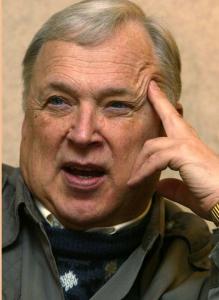

Ted Peters is a pastor, professor, and author of both fiction and nonfiction. Visit: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted is emeritus professor of systematic theology and ethics at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary and the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. He co-edits the journal, Theology and Science at the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences. His fictional thrillers feature an inner-city pastor, Leona Foxx, who courageously challenges the structures of political domination buttressed by the latest in science and technology.

▀

Works Cited

Dawsey, Josh, “Trump derides protections from immigrants from ‘shithole’ countries, The Washington Post (January 12,2018); https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-attacks-protections-for-immigrants-from-shithole-countries-in-oval-office-meeting/2018/01/11/bfc0725c-f711-11e7-91af-31ac729add94_story.html.

Girard, R. (1972). Violence and the Sacred. Baltyimore MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Girard, R. (2001). I Saw Satan Fall Like Lightening. Maryknoll NY: Orbis.

Peters, T. (1992). Atonement and the Final Scapegoat. Perspectives in Religious Studies 19:2, 151-181.

Peters, T. (1993). Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Peters, T. (2015). Sin Boldly! Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Reilly, K. (2016, September 10). Read Hillary Clinton’s ‘Basked of Deplorables’ Remarks About Donald Trump Supporter. Time , pp. https://time.com/4486502/hillary-clinton-basket-of-deplorables-transcript/.

Schwager, R. (1988). The Theology of the Wrath of God. In P. Dumochel, Violence and Truth: On the Work of Rene Girard (p. 51). Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

[1] Josh Dawsey, “Trump derides protections from immigrants from ‘shithole’ countries, The Washington Post (January 12,2018); https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-attacks-protections-for-immigrants-from-shithole-countries-in-oval-office-meeting/2018/01/11/bfc0725c-f711-11e7-91af-31ac729add94_story.html