The Public Theology of Katie Day

The Public Theology of Katie Day

Patheos PT 5003

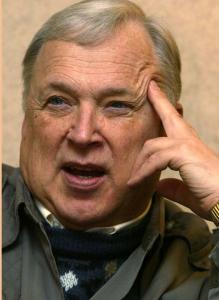

Meet Katie Day. “Public theology is both a matter of reflection and action,” she declares.

Prayer + Action = Progressive Christianity.

“Prayer, as Rabbi Abraham Heschel and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr advocated, is that which we do on our knees and on our feet. I believe the Church and interfaith community is continually called into difficult conversations and sustained work for justice and peace despite formidable challenges.”

The Rev. Dr. Katie Day is an ordained pastor in the PCUSA and emerita professor at United Lutheran Seminary. Along with Sebastian Kim, she co-edited my favorite contemporary volume on public theology, the A Companion to Public Theology (Brill 2017). Here’s a protean definition that appears on page 4 of the introduction to that fine volume. ““Public Theology is thus theologically informed public discourse about public issues, addressed to the church, synagogue, mosque, temple or other religious body, as well as the larger public or publics, argued in ways that can be evaluated and judged by publicly available warrants and criteria.” I would add: the public theologian’s contribution to public discourse is for the sake of the world, not the church.

If you’d like more resources on Public Theology, click here.

I want to know more of what Katie Day thinks.

Katie Day on Discourse Clarification

I recently asked Dr. Katie Day: what definition of public theology do you rely on today?

I stand by that brief definition, although it needs some unpacking. The key word is “discourse”–public theology is about dialogue. It is antithetical to a theological approach that speaks to, rather it talks with. It is the opposite of “God said it, I believe it, that settles it.” So public theologians are in conversations about issues that affect all of us–in and outside of the church–like public health, the climate crisis, immigration, etc. In order to do that we need to get out of parochial God-talk and enter into dialogue with informed language that is accessible to those outside the faith community. In that sense, public theologians need to be multi-lingual (UK theologian Elaine Graham talks about this in her book Between a Rock and a Hard Place.)

According to Day, the public theologian engages in dialogue–that is, listening as well as speaking. The theologian enters fully into public discourse and subjects theological conversation to public warrants and criteria. The theologian dare not hide behind church lingo and in-house allusions.

Elsewhere I have emphasized that discourse clarification is a service the astute theologian can offer to public debate. And I have added worldview construction to the public theologian’s portfolio–that is, offering to the context beyond the church wholesome and holistic alternatives oriented toward God’s grace and the common good.

How does public theology complement or differ from other forms of theology?

Frequently I suggest that public theology is conceived in the church, reflected on critically in the academy, and meshed with the wider culture for the sake of the wider public. So, I asked Dr. Katie Day these two questions: What does public theology hold in common with systematic theology, practical theology, or political theology? What’s different?

When we think of public theology, we gravitate to public theologians–people like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Luther King, Dorothee Soelle, Beyers Naude, or Desmond Tutu. In the present context we could add Delores Williams, Rev. William Barber, and the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians. What is distinctive about them, and all-too-rare, is that their theology is intricately related to their public engagement; action and reflection are inextricably engaged, informing each other. Bonhoeffer always talked about theology being grounded in the concrete realities of our particular contexts. So public theology is not constrained to books and classrooms but is performed in public.

Is the parish pastor also a public theologian?

Because Dr. Day teaches seminarians who become pastors and other kinds of leaders, I posed these questions: Do you believe parish pastors and other church leaders should include a component of public theology in their regular ministerial work? If so, how?

Yes! And where to begin…? Current research by Dr. Leah Schade is showing how clergy are increasingly shy about addressing public issues, fearful of congregational conflict and loss of support in already-declining faith communities now hit hard by the pandemic. Ironically, we also know that public engagement by people of faith is energizing. In his book about clergy involvement in the Civil Rights Movement (Church People in the Struggle) historian James Findlay found through interviews that those engaged “in the struggle” for racial justice had a spiritual rejuvenation. Rabbi Abraham Heschel remarked to Martin Luther King as they were marching that he felt like he was “praying on my legs.” This brilliant Jewish theologian was publicly embodying his faith, and his scholarship.

Many people of faith, including clergy, don’t get involved with public issues because they feel like they don’t know enough and will appear naive. But a season of education to deepen knowledge about a subject is a good place to begin. It is important to focus on an issue and drill down deeply to understand the dynamics and the language around it. For example, if your community has a high rate of gun violence, engage the relevant, multiple “publics” to learn about it–talk with gun owners, families and victims of gun violence, police, politicians and advocates, ER/medical personnel, youth workers. (I choose gun violence as a topic not only because it is a critical issue but it is one that faith leaders are notoriously silent about, except to offer prayers for victims of mass shootings.) How does our faith tradition enable us to understand and respond to the issue? This could easily be the subject of a months-long education program in a congregation. There are risks, of course–our own beliefs about guns could be challenged and changed. But with 40,000 gun deaths each year (a number that has been escalating), we need to risk getting out of our emotional, social, and theological comfort zones.

Many people of faith, including clergy, don’t get involved with public issues because they feel like they don’t know enough and will appear naive. But a season of education to deepen knowledge about a subject is a good place to begin. It is important to focus on an issue and drill down deeply to understand the dynamics and the language around it. For example, if your community has a high rate of gun violence, engage the relevant, multiple “publics” to learn about it–talk with gun owners, families and victims of gun violence, police, politicians and advocates, ER/medical personnel, youth workers. (I choose gun violence as a topic not only because it is a critical issue but it is one that faith leaders are notoriously silent about, except to offer prayers for victims of mass shootings.) How does our faith tradition enable us to understand and respond to the issue? This could easily be the subject of a months-long education program in a congregation. There are risks, of course–our own beliefs about guns could be challenged and changed. But with 40,000 gun deaths each year (a number that has been escalating), we need to risk getting out of our emotional, social, and theological comfort zones.

Too often, we believe that we need to respond to all issues, which finally leaves us overwhelmed and disempowered. Drawing on the body metaphor of I Corinthians 12, we need to focus on a particular function or sense of vocation and trust that other parts of the body can work on those issues we can’t address right now.

Thank you, Dr. Katie Day.

Whither Public Theology?

Not everyone applauds public theology. Evangelical systematician Roger E. Olson does not exactly boo loudly. But he certainly restrains any enthusiasm.

Olson writes: “To me public theology—as a concept, as a phrase, as a label—inevitably carries dangers. Inevitably it will leave out the center, the heart, of Christianity which is Jesus Christ—as more than an example of ‘good humanity’. Public theology has the danger, built into it, of becoming something other than full-blooded, ‘thick’ Christianity.”

Olson wants to protect the Christian gospel from contamination or watering down by non-Christian forces. This defense of orthodoxy is to be commended. Especially when shoring up Christian identity.

But I have a different concern here. When the Christian theologian engages in public discourse, this engagement should offer the world something of value to the world.

Kyle Roberts calls for more public theology that serves the common good beyond the church.

By investing in the public good, theologians take on some of the collective social risk. Conversely, the theologian asks others to share their risk—as mutual investors in the public sphere. Theologians, if they’re like me, can’t offer much cash—but they have something important to give: rich, though flawed, resources from their tradition: Scripture and other religious texts, including a history of intellectual thought—ideas, suggestions, and critiques—and a wealth of diverse spiritual and ecclesial practices (including prayer, confession, repentance, suffering, and thanksgiving).

Recall Paul Tillich‘s method of correlation. The theologian responds with answers to existential questions arising from the culture. Discourse clarification on the part of an insightful pastor or theologian can enhance and deepen contextual understanding. [1] But here is the key: the public theologian’s engagement is for the world, not [only] for the church. The world’s common good includes the church, to be sure; but the public here is the primarily the wider culture.

In this Patheos column, we have listed Public Theology Resources and already met public theologians Karen Bloomquist and Noreen Herzfeld. Here it’s Katie Day. The point we’re pressing is this: might the church theologian be of any value to the world beyond the church? Should we train for this?

The models Katie Day lifts up for us–Bonhoeffer, MLK, Williams, Naude, or TuTu–applied Christian ethics to their respective contexts in hopes of offering the larger society peace or justice. It’s the wider public that should benefit from the efforts of the public theologian.

———————

[1] Recall that for Karl Barth, the theological answer precedes the existential or cultural question. (Karl Barth, Word of God and Word of Man) But this contrast between Tillich and Barth is not as radical as it might first seem. Why? Because of history. The theological answer–the gospel of Jesus Christ–has entered human history through the incarnation and through Scripture. The theological answer has already influenced human culture. We grow up speaking a language in which the theological answer is already embedded, even if in disguised form. The theological answer is already present in our inherited self-understanding, even if vague or contorted. The theological answers offered by the public theologian, therefore, have a likelihood of being intelligible and perhaps accepted.▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Public Christian Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

▓