What is the gospel?

ST 2004

Perhaps the most important question in cosmic history is this: what is the gospel? Here is the answer I tender for your consideration: the gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. In the mind of the systematic theologian: the significance of Jesus’ story comes in three forms: new creation, justification, and proclamation.

Competing on the theological grid iron for the gospel

American evangelicals and progressives are grappling over the gospel like the Pittsburgh Steelers and Green Bay Packers grappling for a fumbled football.

On the one hand, the Together for the Gospel (T4G) team complains that “the Gospel of Jesus Christ has been misrepresented, misunderstood, and marginalized in many Churches.” But T4G doesn’t bother to define this misrepresented gospel. The closest the T4G defense gets is to “affirm that salvation is all of grace, and that the Gospel is revealed to us in doctrines that most faithfully exalt God’s sovereign purpose to save sinners and in His determination to save his redeemed people by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone, to His glory alone.” T4G is in the pile up. But, where’s the football? How will T4G recognize it when they find it?

The Gospel Coalition (TGC) team, however, seems to know what the football looks like. TGC at least centers on a definition.

“We believe that the gospel is the good news of Jesus Christ—God’s very wisdom. Utter folly to the world, even though it is the power of God to those who are being saved, this good news is Christological, centering on the cross and resurrection…”

On the other hand, other evangelical players are scrambling for a different football. It’s called the McKnight–Bates King Jesus football. The King Jesus tacklers are blocking the T4G and TGC ball carriers. There is no way to tell who’s winning. I’m not able to referee.

Even so, this question — what is the gospel? — is important. Whether you are an evangelical, progressive, Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, anti-Christian, or religious skeptic, it only helps to get straight on the gospel. Whether you reject the gospel or commit yourself to becoming martyred because of it, it’s imperative to get it right. This is the imperative taken up by the systematic theologian.

Here, we’ll ask the Bible to get it right for us. But, the Bible takes effort to read. The Bible is a collection of many things, some essential and some peripheral. So, how do we select what is essential? I recommend we discern the central assertion around which other messages appear to be corollaries. When we do this, here is the result of our question: what is the gospel? The gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. Its significance comes in three forms: new creation, justification, and proclamation.

Can we find the gospel in Galatians 3:8?

Can we find the gospel in Galatians 3:8? Yes, says Nijay Gupta. Gupta, a Patheos columnist, attempts to squeeze the gospel out of Galatians 3:8 like a fruit press makes orange juice.

“And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, declared the gospel beforehand to Abraham, saying, ‘All the Gentiles shall be blessed in you’.” (Galatians 3:8)

What Gupta finds in this verse is a personification of Scripture, a blessing to all the Gentiles, and a focus on Abraham instead of the Messiah. Now, I ask rhetorically: how does this help? It confuses the gospel with the grass on the field.

Let me try a more precise description of that gospel football. Let me try to formulate a succinct answer to our question: what is the gospel? Let’s turn to New Testament books such as the Gospels, Acts, and Epistles.

The gospel versus the four Gospels

Might we find the gospel in a Gospel? The term, ‘gospel’, lower case, refers to the central message of the New Testament in abbreviated form. The term, ‘Gospel’, upper case, refers to one or more of the first four books: Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John. [1] I notice that T4G capitalizes the wrong word. Perhaps out of respect.

The Gospel of Mark opens by announcing the gospel of Jesus Christ: “The beginning of the good news [gospel] of Jesus Christ, the Son of God.” Because the word gospel (Greek: τò εὐαγγέλιον) means “good news,” we take it that Mark is referring to the story or the report or the good news regarding the events surrounding the biography of this man, Jesus. The structure of Mark’s Gospel is that of a narrative, a story, a history, an announcement of something that happened. My thesis is that the gospel involves the act of telling the story of Jesus with its significance. The story of Jesus, told with its significance, constitutes the material norm for Christian systematic theology. [2]

The story of Jesus and its significance come to us as a single piece. To say that the story of Jesus is good news already involves a certain level of confession, of commitment to the meaningfulness or significance of this story. In fact, the story in its most compact form of symbolization never appears in the Bible apart from this interpretive perspective. With the Bible as our source, we have no access to Jesus apart from this interpretation. The news of Jesus and its goodness are found together, inseparable. Just how and why it is good news are reflected in the most primitive confessional or kerygmatic formulas.

Can we find the gospel in the Book of Acts?

The sermons of Peter and Paul in Acts provide excellent examples of the gospel in miniature. Because of their function as the first evangelization in the ministry of the early church, we can expect that although brief they will include the essential and unmistakable heart of the primitive Christian message.

Four quite consistent elements appear whenever the story of Jesus is told: (1) the fulfillment of prior Hebrew expectations; (2) the unwarranted death of the righteous one; (3) the resurrection from the dead; and (4) the forgiveness of sins. Whether addressing the people from Solomon’s portico or responding to the threat of prison for preaching in the name of Jesus, the apostles typically recited briefly the history of Israel understood as pointing forward toward fulfillment. This was followed by reporting the execution of Jesus on the cross and his vindication by God through the Easter resurrection. It was further explained that all this happened to affect the forgiveness of sins and the redemption of Israel (Acts 3:12-26; 5:24-32; 10:34-43; 13:16-41). This preaching seems to have come as bad news as judgment to those who rejected it, because it appeared “to bring this man’s blood upon us” (Acts 5:28). But to those among the “great numbers of both men and women” (Acts 5:14) who became believers it was good news because it brought healing into their lives.

These sermon summaries were intended to extend the horizon of the gospel beyond the Jewish tradition to appeal to Gentiles. New Testament historian David Balch stresses that these speeches in Luke-Acts function to widen the scope of God’s grace to include non-Jews, to bring the covenant to all peoples (Balch, 2015, p. 244). Thus, we would expect to find in these sermonic messages the heart of the gospel, the essence of the gospel.

It is likely that the speeches of Peter and Paul reported in the book of Acts are not word for word records of what the apostles actually said. They are probably the compositions of the author of Acts. Yet it is quite likely that they accurately reflect the original. I say this for three reasons. First, because of the “we” passages scholars are generally agreed that the author of Acts must have been a traveling companion for at least some of the adventures reported. Having actually heard the original addresses, the writer could certainly remember the general content of what was said.

Second, the writer declares himself or herself or themselves to be a historian who is attempting to present “an orderly account” of what happened so that the reader can “know the truth” (Luke 1:3,4). There is an avowed attempt to be accurate and to present the truth.

This leads directly to the third and most important reason: it appears that the objective of the original speeches and the objective of the book of Acts are nearly the same. Both are trying to present the gospel. Both constitute a form of evangelization. Even if we do not know word for word what Peter and Paul said on the reported occasions, the author of the Gospel of Luke and the book of Acts is trying to do the same thing as Peter and Paul, namely, to tell the story of Jesus with its significance.

Can we find the gospel in the Epistles?

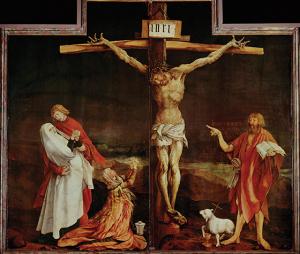

The book of Acts is not the only New Testament source for such brief presentations of Jesus and his significance. For example, 1 Peter 3:18-22 offers a complementary form of gospel presentation. It appears to be an early creedal summary that most probably predates the letter itself. Some scholars contend that behind this text is an early Christian hymn similar to the ones quoted in 1 Timothy 3:16 or even Philippians 2:6-11 and Colossians 1:15-20. In a mode of expression anticipating the Roman Symbol and the Apostles’ Creed, the 1 Peter text follows Christ’s resurrection with his exaltation to the right hand of God and its efficacy for the believer in baptism.

The heart of the statement is the report of the righteous one who died for the unrighteous. This results in the forgiveness of sins—Xριστòϛ ἅπαζ περὶ ἀµαρτιϖν ἒπαθεν (or ἀπέθανεν), δίκαιοϛ ὑπὲρ ἀδίκων—in order that he might bring us to God (1 Peter 3:18). The substitution of the righteous Christ for the unrighteous sinner, perhaps connoting a sacrificial offering (Lev. 14:19 in LXX), establishes for us a new rapport with God. We might consider 1 Peter 3:18 the gospel in a single sentence, the story and its significance in a single statement.

[I don’t take sides here regarding the claim that penal substitution should be the one and only model of atonement.]

Another NT story of Jesus told with its significance? Paul’s kerygmatic formulation in 1 Corinthians 15:3-8 includes many of the elements we identified in Acts: “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, . . . was buried, . . . was raised on the third day, . . . appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.” Hence, by “story of Jesus with its interpretive significance” I do not necessarily mean the full-blown narratives of the Synoptic Gospels. These came later. What I mean is the reference to certain indispensable historical occurrences in the career of Jesus that establishes that God has worked definitively to accomplish salvation.

The significance of the story of Jesus is that it announces our salvation. Systematic theology may spell out this significance in terms of three New Testament themes: the gospel as new creation, justification, and proclamation.

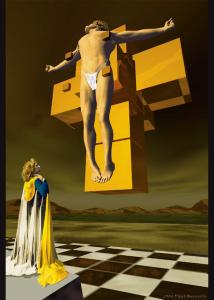

1. The Gospel as New Creation

New Testament historian N.T. Wright draws out the significance of the story of Jesus in terms of eschatological new creation.

“The good news was, and is, that all this has happened in and through Jesus [death and resurrection]; that one day it will happen, completely and utterly, to all creation; and that we humans, every single one of us, whoever we are, can be caught up in that transformation here and now. This is the Christian gospel. Do not allow yourself to be fobbed off with anything less” (Wright, 2015, p. 54).

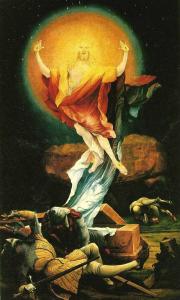

As Wright rightly sees, the resurrection of Jesus is an irreplaceable part of the gospel account in the New Testament. This includes Paul as well. The power of resurrection is tantamount to the power to create, and this power belongs to God alone, “who gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Rom. 4:17).

It is also significant for Paul because the resurrection of Jesus confirms the long-standing Hebrew hope for the final triumph of God’s justice. The end of the age and the resurrection of the dead envisioned by apocalyptic seers have already occurred proleptically in Jesus Christ, and those who are united with Christ through faith are already participants in the new creation that is yet to come for the whole cosmos. The gospel communicates that on account of Christ, God’s future is spiritually present now, imbuing us with newness of life and inspiring hope while granting us peace of mind.

In Christ, God’s justice has triumphed. Justice (or righteousness, Hebrew: sdqh , _דקה ) is the central concept in the Old Testament for discerning the quality of all relationships between God and humanity, within human community, and even with nature. Sdqh, translated δικαιοσύνη in the Septuagint and justitia in the Vulgate, is the highest value in life, that upon which all reality rests when properly ordered. The king as Yahweh’s messiah, the one anointed to rule, is supposed to govern with righteousness and justice, and this means protecting the poor and caring for the widow and orphan (Ps. 72:1-4). With the Babylonian captivity Israel begins to hope for the future, to hope for a messianic king who will establish a kingdom of divine justice (Jer. 23:5; Isa. 51:5; 54:1417; 59:16-17).

During the intertestamental period this hope gets cosmicized and transmuted to the age to come. The apocalyptic pessimism regarding the present aeon and doctrine of the two ages accents the need for God to intervene in terrestrial affairs and “bring in everlasting righteousness” (Dan. 9:24). Where human justice is so lacking, only the justice of God will do. So Jews under the oppression of the Seleucids longed for the age to come. The sign of the arrival of the New Age would be the resurrection of the dead. This apocalyptic vision of resurrection and transformation decisively conditions Paul’s experience and his evangelical explication of the gospel.

Jesus’ Easter resurrection as prolepsis of new creation

Jesus Christ is “the first fruits of those who have died,” Paul tells the Corinthians (1 Cor. 15:20b; cf. Rom. 8:19; Col. 1:18). Recall how he opens chapter 15 with a creedal summary of the gospel as story reminiscent of the sermons in Acts: “Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures. . . . He was buried. . . . He was raised on the third day” (1 Cor. 15:3-4). Now Paul is unpacking this compact formula in light of the Corinthian situation. Questions have come to Paul concerning such things as a case of incest, marriage, decorum at the Lord’s table, spiritual gifts, and so forth.

Of course the dead will be raised! exclaims Paul. If this were not so then there would be no gospel and no forgiveness and no hope: “For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1 Cor. 15:16-19). There is no doubt here that there is no gospel without resurrection.

Paul then proceeds as he does in Romans 5 to contrast the present age identified with adam and death with the future age identified with Christ and resurrection to life. Christ is the avant garde, the embodiment in advance of the new order that is to come. Employing apocalyptic imagery Paul looks forward to the ultimate future when the messianic king will establish the age of God’s justice: “Then comes the end, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father, after he has destroyed every ruler and every authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. . . . When all things are subjected to him, then the Son himself will also be subjected to the one who put all things in subjection under him, so that God may be all in all” (1 Cor. 15:24-26, 28). Salvation does not consist in some sort of individual escape from the physical realm of history into a transcendent realm of soul or spirit. Rather it is contingent upon the transformation of the created order, on the divinely promised redemption of the cosmos.

The victory of Christ over the grave and the new life promised to us are part of something much bigger, namely, the triumph of God over the enemies of divine justice, including the triumph over death. The resurrection victory of Christ is a prolepsis; it is an advance incarnation of the yet-to-come new order of creation.

Since New Testament times the size of the cosmos has expanded in our imaginations. No longer do we limit the scope of God’s creation and redemption to planet Earth. The concept of creation now includes an immense universe with a 13.82-billion-year past and perhaps a 100 billion year future with billions of galaxies and uncountable stars and planets. When today’s theologian repeats the biblical promise of a coming new creation, it applies to all that exists both in the depth of the human soul and the breadth of a near immeasurable universe.

The vision of the new creation and proleptic Eco-Ethics

The vision of the new heaven and new earth becomes the guide for ecological ethics today. Our eco-task is to make our world today emulate God’s promised world of tomorrow. Homiletical theologian Leah Schade puts it this way: “As we trust God’s promise of a ‘new heaven and a new earth’, the church’s work in Creation care is consistent with what God wants for the world now and what God will bring about for all Creation in the fulfillment of time.”

God is the world’s future. God’s final future takes the form of the new creation, symbolized in the New Testament as the Kingdom of God. The gospel message, then, is that we have grounds for hoping in the transformation of a world gone astray and that through faith in Christ the power of the future new creation and the justice of God’s future rule become part and parcel of our life today. “So if any one is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new. . . . For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God [δικαισύνη Θεоû]” (2 Cor. 5:17, 21; see Rom. 6:1-11).

2. The Gospel as Justification

Thus, the story of Jesus is significant first of all because it signals the coming of the new creation. It is the power of new life. But this is not the only way of expressing its significance within the matrix of New Testament symbols. The notion of justification by God’s grace through faith is tied intimately to the gospel as well.[3]

Despite this, Roman Catholics and evangelicals try to sack the quarterback before justification can get centered. “It’s quite curious to me,” declares Patheos columnist David Armstrong, “that so many Protestants want to define the gospel in the strict sense of ‘justification by faith alone’, when the Bible itself is very explicit and clear that this is not the case at all.”

“Justification by faith is not the gospel,” touts Patheos columnist Michael Bird. Well, then, what is it? Bird says, “it is a Pauline explanation for how the gospel saves.” Oh! The gospel is one thing. And salvation is another. “Yes,” Bird adds, “there is a close relationship between gospel and justification/righteousness.”

I find Armstrong and Bird confusing. So, I’d like to get more precise. Justification is the significance of the story of Jesus. This significance is built into the story of Jesus. Without justification, no gospel.

Justification is the means by which God saves us. The gospel “is the power of God for salvation,” writes Paul (Rom. 1:16). He makes this point especially in the context of Jewish-Christian relations in the letters to the Galatians, Philippians, and Romans.8 The situation in Galatia is that Paul has to defend his gospel and apostleship against the attacks of interlopers who teach “another gospel” (Gal. 1:7, 9; 2:12; 3:1; 5:7, 9, 12), those whom he calls “dogs” in Philippians 3:2. The dogs are barking out a false gospel and confusing the churches. Presumably they are Jewish-Christian missionaries rivaling Paul by teaching that outside the Torah there is no salvation. They are requiring that in order to obtain justification—that is, righteousness in the eyes of God— believers in Christ must become circumcised and fulfill additional requirements of the Jewish law.

The essence of sin is our feeble attempt at self-justification through doing works of the law. God’s response is to justify us by grace, eliminating the need for our self-justification. Paul responds categorically: “A person is justified [δικαιоsunαι] not by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ” (Gal. 2:16). Paul excludes works of the law from the content of the gospel. If this were not true, he says, “then Christ died for nothing” (Gal. 2:21). If Christ is the proleptic embodiment of the fullness of God’s justice in the new creation, and if we are united with Christ through faith and therefore with that righteousness, then conformity to the laws of the old creation simply has no influence on our salvation.

The net effect of this interpretation of the gospel in this context is to establish equality at the foot of the cross. It counters the claim for superior status by Jewish Christians within the church. With eloquence and passion Paul trumpets: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28). Biblical historian N.T. Wright does the work of the systematic theologian here.

“This is the three-dimensional meaning of ‘justification by faith’: all those who believe in Jesus, rescued by his cross and resurrection and enlivened by his Spirit, are part of the new family. This was and is central, not peripheral. The church was the original multicultural project, with Jesus as its only point of identity. It was known, and was for this reason seen as both attractive and dangerous, as a worship-based, spiritually renewed, multi-ethnic, polychrome, mutually supportive, outward-facing, culturally creative, chastity-celebrating, socially responsible fictive kinship group, gender-blind in leadership, generous to the poor and courageous in speaking up for the voiceless.”

But, should justification be central?

“Scripture never says our justification by faith is part of the gospel,” declares a Patheos columnist. What? Really? Now, I’m confused again. In the Patheos debate over the gospel, we see ambivalence. On the one hand, justification is decisive to the gospel. On the other hand, it’s not central. Scot McKnight makes Jesus’ kingship central. Yet, he has good things to say about justification, even though it’s allegedly “unbiblical.”

Deriving from Martin Luther, “is the centrality of justification by faith to the gospel itself. OK, Luther was right: his perception of justification focused on God’s grace and our sinfulness and our inability to please God and the incongruity of God’s grace and human deserving. That drove Luther, and he was right. In his day, he could do no other.”

However, McKnight goes on.

“It [justification by grace through faith] tends to be explanatory: one can make anything central if one uses it to explain everything else. But it’s unbiblical because one finds the term justification three times in the Gospels (Luke 10:29; 16:15; 18:14). Rare is the point. When one presses this too hard one discovers that Jesus didn’t or rarely did preach the gospel of the centrality of justification. That’s a serious mistake. Jesus, instead, chose kingdom to express his gospel. That’s why the Evangelists say he preached the ‘gospel of the kingdom’. He preached the gospel… he is the gospel. Everywhere he went he was gospeling. He was the ‘autobasileia’, the kingdom itself.”

So, where does this leave the systematic theologian? Confused?

Let me suggest that justification by divine grace is announced with the story of Jesus. This is made more clear when drawing out the significance of Jesus as the Messiah. Included in the significance of Jesus’ story is our justification by God’s grace (Luther, 2015-2020).

Justification anticipates New Creation

When pursuing systematic theology, we should note that the explication of the gospel in terms of justification is at least in part dependent upon its explication in terms of new creation. The justice of God of which Christ is the proleptic embodiment is for us still an eschatological hope. We are still sinners, still participants in the injustice of the old order. Yet in Christ we participate as well in the justice of the expected new order.

Thus, there is a double character to justification. On the one hand, it is a firm and present possession that yields peace in our lives (Rom. 5:1-5). On the other hand, it lies in the future. “For through the Spirit, by faith, we eagerly wait for the hope of righteousness [δικαισύνη]” (Gal. 5:5). Joachim Jeremias calls this an “antedonation” of God’s final salvation, the beginning of a movement toward a goal, namely toward the hour of the definitive justification, of the acquittal on the day of judgment, when the full gift is realized (Jeremias, 1965, p. 65). Instead of antedonation I prefer the term prolepsis, indicating that the future reality is here ahead of time. Wolfhart Pannenberg writes, “The resurrection of Jesus is the proleptic manifestation of the reality of the new, eschatological life of salvation in Jesus himself” (Pannenberg, 1991-1998, p. 3:627). Through faith in Christ we today are citizens of two aeons, the future and the present. We are justified because participation in the future consummation of God’s justice is given to us now, ahead of time, through faith.

We are called to work for justice in an unjust world. No matter how hard we work to increase justice, we ourselves will not establish complete justice. Only the future kingdom of God will do that.[4] Yet, curiously enough, that future complete justice becomes ours now, ahead of time, proleptically. We are now both sinful and just, awaiting the perfection of justice.

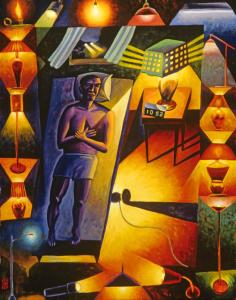

3. The Gospel as Proclamation

I have been saying that the gospel is the report of divine grace that establishes justification and opens the door to new creation. But it is more than a report, much more. The very telling of the gospel participates in the reality of the gospel itself. The gospel is news. And, as such, it presses to be told and retold. The gospel when preached is not merely information or even revelation about justice. Rather, the very preaching itself makes that divine justice a possibility for the hearer. The proclamation of the news itself bears the power of salvation.

A former cardinal and former pope, Benedict XVI, designates the gospel’s proclamation a “performative” utterance. “The evangelium, the Gospel, is not just informative speech, but performative speech—not just the imparting of information, but action, efficacious power that enters into the world to save and transform” (Pope, 2007, p. 47).

Because the power of the gospel is borne by preaching, it has an ambivalent relationship to written scripture and tradition. On the one hand, Paul denies any dependency upon the apostolic tradition that preceded him. “I did not confer with any human being,” he declares in Galatians 1:16. He received the gospel from direct revelation, from his vision of the resurrected one on the road to Damascus and perhaps an ecstatic experience in the desert of Arabia. Paul does not need to appeal to the authority of the original apostles because the gospel is not simply a bundle of teachings or traditions that can be memorized and transmitted. It is not a finished depositum fidei or timeless dogma. It is itself the manifesting of the Spirit in the world. Hence, it is something that lives.

On the other hand, Paul occasionally talks about the gospel as a tradition (παράδоσιϛ) or teaching (διδαχή) that can be handed down and that needs to be preserved. In Paul’s preaching he passes on what he has received (1 Cor. 15:1-4).

What had he received? Most probably a version of the Jesus story told by Christians in Antioch. This he passes on to the Corinthians and others. Nevertheless, his radical appropriation and reinterpretation of such things as the Jewish law in the doctrine of justification show a creative appropriation of what he received. Paul does more than merely repeat what he has heard. Even the “ancestral traditions” (Gal. 1:14) come to life in a new way for Paul when they help bear the gospel, when they become part of the nascent new tradition.

Thus, a gospel-oriented tradition is being born in the era of Paul. The gospel has a flexible content that can be passed on through teaching. Be that as it may, the content of the gospel comes to life only through its proclamation. Tradition clearly stands in the service of preaching, not vice versa. There is something elusive and alive about the gospel that makes it subject to tradition, yes, but always something more than tradition.

The idea of the spoken word—the word of God—is key to understanding the living tradition of the gospel. The whole life and destiny of Jesus are in their unique way God’s word spoken to the world. Jesus Christ is the living word, the viva vox. This makes telling the story of Jesus divine address. So for the church to present the gospel through preaching or teaching is to participate in the very activity whereby God addresses the world. Through our re-presenting the originary symbols of the gospel experience as reported to us in the New Testament, God actually calls people to live in the light of the revelatory action. Telling and listening to the story of Jesus with its significance are themselves part of the ongoing work of God.

Conclusion

In the scramble for the gospel football on the theological grid iron, it is somewhat embarrassing that competing teams cannot agree on what it is they are fighting for. This is no trivial matter, because truth is at stake.

We Christians deem the gospel to be the truth, the ultimate truth. When we tell the story of Jesus with its significance, we are proclaiming what has been revealed to us about God in the cross and resurrection. Ultimate reality has spoken. The gospel tells us what ultimate reality has said, albeit in historically conditioned symbols.

In summary, we have been asking a question that should have a succinct answer within systematic theology: what is the gospel? I have been answering this way: the gospel is the story of Jesus told with its significance. What is that significance? New creation. Justification. Proclamation.

▓

Ted Peters is a Lutheran pastor and emeritus seminary professor, teaching theology and ethics. He is author of Short Prayers and The Cosmic Self. His one volume systematic theology is now in its 3rd edition, God—The World’s Future (Fortress 2015). His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He has undertaken a thorough examination of the sin-and-grace dialectic in two works, Sin: Radical Evil in Soul and Society (Eerdmans 1994) and Sin Boldly! (Fortress 2015). Watch for his forthcoming, The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com.

Ted Peters’ fictional series of espionage thrillers feature Leona Foxx, a hybrid woman who is both a spy and a parish pastor.

▓

[1] This discussion follows an earlier exposition of the gospel in God—The World’s Future (Peters, 2015, pp. 84-96).[2] “The word ‘Gospel’ in the New Testament has the concrete meaning of witness to the Jesus of history….an apostle…does not merely relate the facts about Jesus but proclaims the meaning behind these facts. He proclaims Jesus as Lord, the Messiah of Israel and the Saviour of the world” (Barth, 1936-1962, p. III/2: §47: 473).

[3] “When I hear the gospel, that I have been accepted and adopted by God for the sake of Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit, I am radically passive. I receive that which is given to me as a ‘categorical gift’” (Bayer, 2007, p. 11).

[4] The eschatological kingdom of God has been associated with one of the three offices of Christ, the triplex munus: Jesus Christ as prophet, priest, or king. Curiously, when specifying the essence of the gospel, Baptist Greg Gilbert conflates the offices of priest and king. “So the story of Jesus’ death is screaming to us that, in some beautifully and yet wrenchingly ironic way, Jesus is dying not just as priest, but as king. His death is somehow particularly and uniquely king-like work…Here’s what I want you to see and rejoice in today: Jesus’s death in his people’s place, his salvation of them from their sins, is naturally, rightly, and inherently tied to his office as king.” In short, the gospel significance is that Christ is King.

Works Cited

Balch, D. (2015). Contested Ethnicities and Images. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Barth, K. (1936-1962). Church Dogmatics, 4 Volumes. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

Bayer, O. (2007). With Luther in the Present. Lutheran Quarterly 21:1, 1-19.

Jeremias, J. (1965). The Central Message of the New Testament. New York: Scribners.

Luther, M. (2015-2020). The Freedom of a Christian. In M. Luther, The Annotated Luther, 5 Volumes (pp. 1: 467-518). Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Pannenberg, W. (1991-1998). Systematic Theology, 3 Volumes. Grand Rapids MI: Wm B Eerdmans.

Peters, T. (2015). God–The World’s Future: Systematic Theology for a New Era (3rd ed.). Minneapolis MN: Fortress Press.

Pope, B. X. (2007). Jesus of Nazareth. New York: Doubleday.

Wright, N. T. (2015). Simply Good News. New York: Harper.