Religious Transhumanism?

H+ 15 / 2025: Lutheran Transhumanism?

Can we conceive of a distinctively Lutheran transhumanism?

Other Christians like transhumanism. Evangelical Micah Redding has already launched the Christian Transhumanist Association. “Christian Transhumanists will continue to advance the vision of a radically flourishing future that is good for all life”(Redding, 2019, 794). With this in mind, can we imagine a distinctively Lutheran transhumanism? Let’s explore this question.

When it comes to justification-by-faith, Lutherans are on top of it. When it comes to forgiveness of sins, Lutherans greet it with joy. When it comes to living daily in faith and thanksgiving, Lutherans express the joie de vie.

But, when it comes to sanctification, where are the Lutherans? Justification, yes indeed! Sanctification, huh? The following was not written by a Lutheran.

You were taught to put away your former way of life, your old self, corrupt and deluded by its lusts, and to be renewed in the spirit of your minds, and to clothe yourselves with the new self, created according to the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness. (Ephesians 4:22)

Lutherans understand with profundity the dynamic of simul justus et peccator. This means living daily as a forgiven sinner. The life of a forgiven sinner is joyous because it relies consciously on God’s gracious love for all that is important in life and in death. But, what about transformation? What might attract a Christian to transhumanism would be the employment of technological enhancement in the process of sanctification.

On one occasion, the renowned Lutheran theologian, Gerhard Forde, came to my home for a barbecue. He was wearing a sweat shirt that read: “I Don’t Believe in Sanctification.”

With this as background, then, as an exercise in public theology we ask: what in the world would a Lutheran do when confronted with the promises of transhumanist technology? Could we conceive of a distinctively Lutheran transhumanism? Let’s ask Noreen Herzfeld.

Meet Noreen Herzfeld Again

Perhaps you remember Noreen Herzfeld. She’s a public theologian who teaches both computer science and systematic theology to students at St. John’s University and the College of St. Benedict. What is the title of her faculty chair? She is the Nicholas and Bernice Reuter Professor of Science and Religion. In my opinion, Professor Herzfeld is one of the finest experts on the topic we are trying to analyze.

Noreen teaches in a Roman Catholic setting. Noreen was baptized and confirmed Lutheran, even though she now identifies as a Quaker. She is a Minnesota Ole. Her value to us here is this: she thinks like a Lutheran. So, we will ask her here to think like a Lutheran on the matter of transhumanism.

1. Noreen, your chapter in Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics has the title “Ghosts or Zombies: On Keeping Body and Soul Together.” On the relationship between soul and body, what problem does transhumanism pose?

Noreen Herzfeld. Much of transhumanism is based on a neo-Cartesian belief that the soul is separable from the body. The difference between the transhumanists and Descartes is that, while Descartes sees the soul as pre-existing the body, transhumanists want the mind or person (their version of soul), to be post-existent from the body. In other words, they believe that what essentially makes us “us” is information, the pattern of memories, experiences, and proclivities stored in the neurons of our brain. They see no reason why this pattern could not be instantiated in a different medium, such as the silicon chips of a computer. They find our bodies, with their illnesses, frailty and ultimate death, distasteful, something to be transcended. The “trans” in transhumanism strikes me as being mostly about transcending the evil body in favor of the perfect life of the mind—a sort of Gnosticism revisited.

There are several problems with this. First, it fails to take into account the fact that our neural connections are vast (billions) and are constantly changing. When should I download my brain? When I’m young and know everything? Or when I’m old and have more memories? How about both? But then, which one is me?

Second, we have a “second brain” in our gut. There are reasons we speak of having a “gut feeling” about something.

And feeling brings up a third problem. neuropsychologist Antonio Damasio has shown that emotion is key, not only to who we are, but to our decision making and even much of what we consider “rational” thought. But emotion is rooted in the body. Imagine being out on a hike an hearing a rustling in the underbrush. Your body goes into “fight or flight” mode with a rapid heartbeat and adrenaline surge long before your cerebral cortex kicks in. Emotions are felt in our bodies before they occur to our minds.

While a disembodied mind is a source of hope for transhumanists and AI entrepreneurs, it has been a source of horror in folklore and literature. A soul without a body, and the converse, a body without a soul, have been staple themes of films and the late-night stories children scare each other with around the campfire. We call these ghosts and zombies. While the transhumanists envision a future in which we are essentially ghosts, I fear, as I watch my students shambling mindlessly across campus, eyes glued to their phones, that computers are actually turning us into zombies (Herzfeld, Ghosts or Zombies: On Keeping Body and Soul Together 2022a).

2. When it comes to embodiment, why would transhumanism pose a problem for a Lutheran?

Noreen Herzfeld. So what does this have to do with Lutherans? The Christian tradition brings to the religious table a unique emphasis on embodiment. In the incarnation, our God took on a human body, with all its weaknesses. We cherish, in the words of Catholic theologian Adam Cooper, “a personal, ritual, narrative and social” encounter with our God, who we know understands our human condition, having been there, done that.

For Lutherans, relationship with God is fostered through the liturgy and the sacraments, deeply embodied and material experiences. According to philosophers Lakoff and Johnson: “Our body is intimately tied to what we walk on, sit on, touch, taste, smell, see, breathe, and move within.” [1] In the liturgy, we sit, and kneel, we feel the water of our baptism, we taste the bread and wine that are as physical as the body and blood of Jesus, our eyes take in icons, statues, or soaring architecture, we breathe in the smoke of incense, we feel the our neighbor’s hand in the passing of the peace, and we sing out hearts out. These experiences involve the whole person, not just the mind.

We believe embodiment is so important that it continues even after death. In the Apostles Creed we say we believe in the “resurrection of the body” not in some disembodied flight of the soul to heaven. To be a unique self requires a body. Lakoff and Johnson argue that the embodied mind calls Christian tradition into question. If, by Christian tradition, they mean folk piety, they may have a point. Many Christians speak and act as if they were a soul that merely inhabits a body for a time, leaving that body and heading to heaven (or hell) upon death. We speak as if our bodies aren’t the “real” us. But I think the pandemic gave us a good lesson about that. Not only did we all become hyperaware of our bodies and those of others, but we also saw how partial and unfulfilling meeting one another in Zoomland was.

3. In the Lutheran interpretation of the Sacrament of the Altar, the body and blood of Christ are truly present in, with, and under the bread and the wine. Is there any room within religious transhumanism for such a sacramental theology?

Noreen Herzfeld. Martin Luther was deeply concerned with the question of justification. How could we as sinners possibly be worthy of God’s grace and redemption? He saw the sacraments as a visible, tactile way for God to draw close to us and to our human condition. The sacraments of baptism and communion bring together the mental and the material, word and action. By saying the body and blood of Christ are present “in, with, and under” the bread and wine, Lutherans are trying to express something inexpressible, that Jesus truly comes to us, not just in our memories of his life and teaching, not just in words and symbols, but in the everyday material of our existence, indeed, in the things we most need to sustain life—food and drink.

Transhumanists, in their desire to transcend the body and the material world, would see little significance in this. Who needs food and drink or even the physical presence of a loved one if we can have it all as a purely mental experience? But we are not purely mental creatures. We are flesh and blood, and it is through flesh and blood that we enter into the fullest relationship with one another, and with our God. This makes a distinctively Lutheran transhumanism unlikely if not anathema.

4. If a Lutheran must choose between (1) Radical Life Extension, (2) cybernetic immortality, or (3) resurrection of the body, which will it be? Which do you believe to be most authentically Christian?

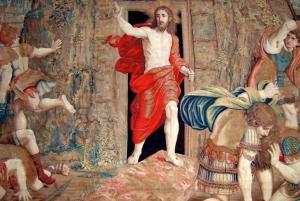

Noreen Herzfeld. The answer is obvious. St. Paul stresses that Jesus’s bodily resurrection from the tomb is the template for our own resurrection. Jesus isn’t resuscitated nor simply a continuing inspiration through the memories of the apostles. Nor is he a disembodied soul. He returns in a body, albeit a somewhat different one. He eats and drinks. Thomas places his hand in the wound in Jesus’s side. The wounds show that it is his body, exalted, yet still congruent with the body that died. This is quite different from the transhumanist belief that we could live on within a machine. Such a life would be merely a continuation of one part of our self as a way of cheating death. But Jesus did not cheat death. He died. The resurrection does not undo or go around death. Rather, God creates a new future. As Catholic theologian Karl Rahner puts it: “it is not as if in death he just changed horses and rode on.”[2]

I’ve also felt there is something massively narcissistic in transhumanism. While I hope for a reasonably long life for myself and those I love, why should I continue too long on this earth? What resources would I use that could better serve future generations? What is so great about my mind that it should be immortalized in a machine? And would it be happy there or would it languish without a body, without the physical delights of food and wine, of touching another, of sex. Not simulated touching, simulated sex, but the real, messy, vulnerable ding an sich?

At the end of the movie Manhattan, Woody Allen asks the question, “What makes life worth living?” His character answers:

Why is life worth living? That’s a very good question. Well, there are certain things I guess that make it worthwhile. Like what? Okay, for me, I would say, Groucho Marx, to name one thing and Willie Mays, and the second movement of the Jupiter Symphony, and Louie Armstrong’s recording of “Potato Head Blues,” Swedish movies, naturally, “Sentimental Education” by Flaubert, Marlon Brando, Frank Sinatra, those incredible apples and pears by Cézanne, the crabs at Sam Wo’s, Tracy’s face …

What makes life worth living is not the information encoded in each of those things. It is the things themselves. It is the way they make us feel. It is an embodied love that we see, hear, taste, touch, and cherish. We believe in the resurrection of the body for precisely this reason.

5. You are a public theologian. What is the responsibility of the public theologian in this age of AI, IA, and H+?

Noreen Herzfeld. To speak up (Herzfeld, Introduction: Religion and the New Technologies 2017). Our culture adores everything that is new and shiny. Right now artificial intelligence is a big buzzword (Herzfeld, In Our Image: Artificial Intelligence and the Human Spirit 2002). We want to see our own image reflected in our creation—we attribute sentience where it does not exist, and we look at immortality as if it were just another do-it-yourself project. The promises of technology, always just around the corner or out of reach, can blind us to what we are called by our God to do here and now—to heal the sick, help the suffering, grieve with those who grieve, and love and honor our material selves and our material environment. That is why I have written a second book about AI, coming out in January from Fortress Press. Entitled The Artifice of Intelligence: Human and Divine Relationship in a Robotic Age, this book examines what the ubiquity of computers, and especially what we call AI, is doing to our relationships, with one another, with the earth, and with God. And it has a great foreword by Ted Peters!

Where have we been?

This Patheos series on public theology has been asking about the religious implications of the transhumanist movement. Here’s where we have been so far.

H+ 1:Is AI a shortcut to virtue? To holiness?

H+ 2: The Transhuman, The Posthuman, and the Truly Human

H+ 3: Radical Life Extension? Cybernetic Immortality? Or Resurrection of the Body?

Religious Transhumanism 4: Evangelical? Yes. Meet Micah Redding

Religious Transhumanism 5: Mormon? Yes. Meet Lincoln Cannon

Religious Transhumanism 6: Jewish? No. Meet Hava Tirosch-Samuelson

Religious Transhumanism 7: Buddhist? Yes. Meet Michael LaTorra

Religious Transhumanism 8: UU? Yes. Meet James Hughes

Christian Transhumanism versus Transhumanist Christianity

Religious Transhumanism 10: Transhumanism vs Posthumanism

Religious Transhumanism 11: What about the body? Meet Jamie Fowler

Religious Transhumanism 12: Catholic? Meet Brian Patrick Green

Religious Transhumanism 13: Methodist? Meet Alan Weissenbacher

Religious Transhumanism 14: Scientific? Meet Arvin Gouw

Religious Transhumanism 15: Lutheran? Meet Noreen Herzfeld

Conclusion: Lutheran Transhumanism? Not Likely.

Is a distinctively Lutheran transhumanism likely? No, according to Noreen Herzfeld. Why? Because transhumanist assumptions and goals about dislodging the mind from its bodily substrate fails to appreciate how God appreciates our embodiment.

Like Noreen Herzfeld, Carmen Fowler LeBerge alerts Christians to be cautious when embracing emerging AI technologies.

“The challenge for Christians interested in engaging in this conversation will be conversation without compromising the fundamental Christian understanding of the imago Dei, humanity, life, the body, and the vision of the future”(LaBerge, 2019, 771).

▓

Ted Peters pursues Public Theology at the intersection of science, religion, ethics, and public policy. Peters is an emeritus professor at the Graduate Theological Union, where he co-edits the journal, Theology and Science, on behalf of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, in Berkeley, California, USA. His book, God in Cosmic History, traces the rise of the Axial religions 2500 years ago. He previously authored Playing God? Genetic Determinism and Human Freedom? (Routledge, 2nd ed., 2002) as well as Science, Theology, and Ethics (Ashgate 2003). He is editor of AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? (ATF 2019). Along with Arvin Gouw and Brian Patrick Green, he co-edited the new book, Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics hot off the press (Roman and Littlefield/Lexington, 2022). Soon he will publish The Voice of Christian Public Theology (ATF 2022). See his website: TedsTimelyTake.com. His fictional spy thriller, Cyrus Twelve, follows the twists and turns of a transhumanist plot.

▓

Notes

[1]. Lakoff and Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh, 565.

[2]. Karl Rahner, “On the Theology of the Incarnation,” Theological Investigations IV. (New York: Seabury Press, 1974), 110.

References

Herzfeld, Noreen. 2022a. “Ghosts or Zombies: On Keeping Body and Soul Together.” In Religious Transhumanism and Its Critics, by Brian Patrick Green, and Ted Peters, eds Arvin Gouw, 309-320. Lanham MA: Lexington.

—. 2002. In Our Image: Artificial Intelligence and the Human Spirit. Minneapolis MN: Fortress.

Herzfeld, Noreen. 2017. “Introduction: Religion and the New Technologies.” Religions 8:7 1-3.

LaBerge, Carmen Fowler, 2019. “Christian Transhumanism? A Christian Primer for Engaging Transhumanism.” The Transhumanist Handbook. Ed., Newton Lee. Heidelberg: Springer, 771-776.

Peters, Ted. 2019. AI and IA: Utopia or Extinction? Adelaide: Australian Theological Forum.

Peters, Ted. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism, and Rival Salvations.” Covalence https://luthscitech.org/artificial-intelligence-transhumanism-and-rival-salvations/.

Peters, Ted. 2019. “The Ebullient Transhumanist and the Sober Theologian.” Sciencia et Fides 7:2 97-117.

Peters, Ted. 2022b. The Transhuman, the Posthuman, and the Truly Human. Column, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/publictheology/2022/01/h-2-the-transhuman-the-posthuman-the-truly-human/: Patheos Public Theology.

Redding, Micah, 2019. “Christian Transhumanism: Exploring the Future of Faith,” The Transhumanism Handbook. Ed., Newton Lee. Heidelberg: Springer, 777-794.

▓