We start by collecting the earliest and best-attested Kingdom sayings throughout the gospels; I have used those identified by John Dominic Crossan in his book “Jesus: The Life of A Mediterranean Jewish Peasant.” These are the sayings most likely to be authentic words of Jesus because, as Crossan puts it, they are the ones “where at least two independent sources claim the Kingdom expression” (Crossan 459). I have only included these sayings from what Crossan identifies as the first (earliest) stratum of material, which ends with Mark (or possible the Didache, see below) and includes the hypothetical Q document as well as the Gospel of Thomas.

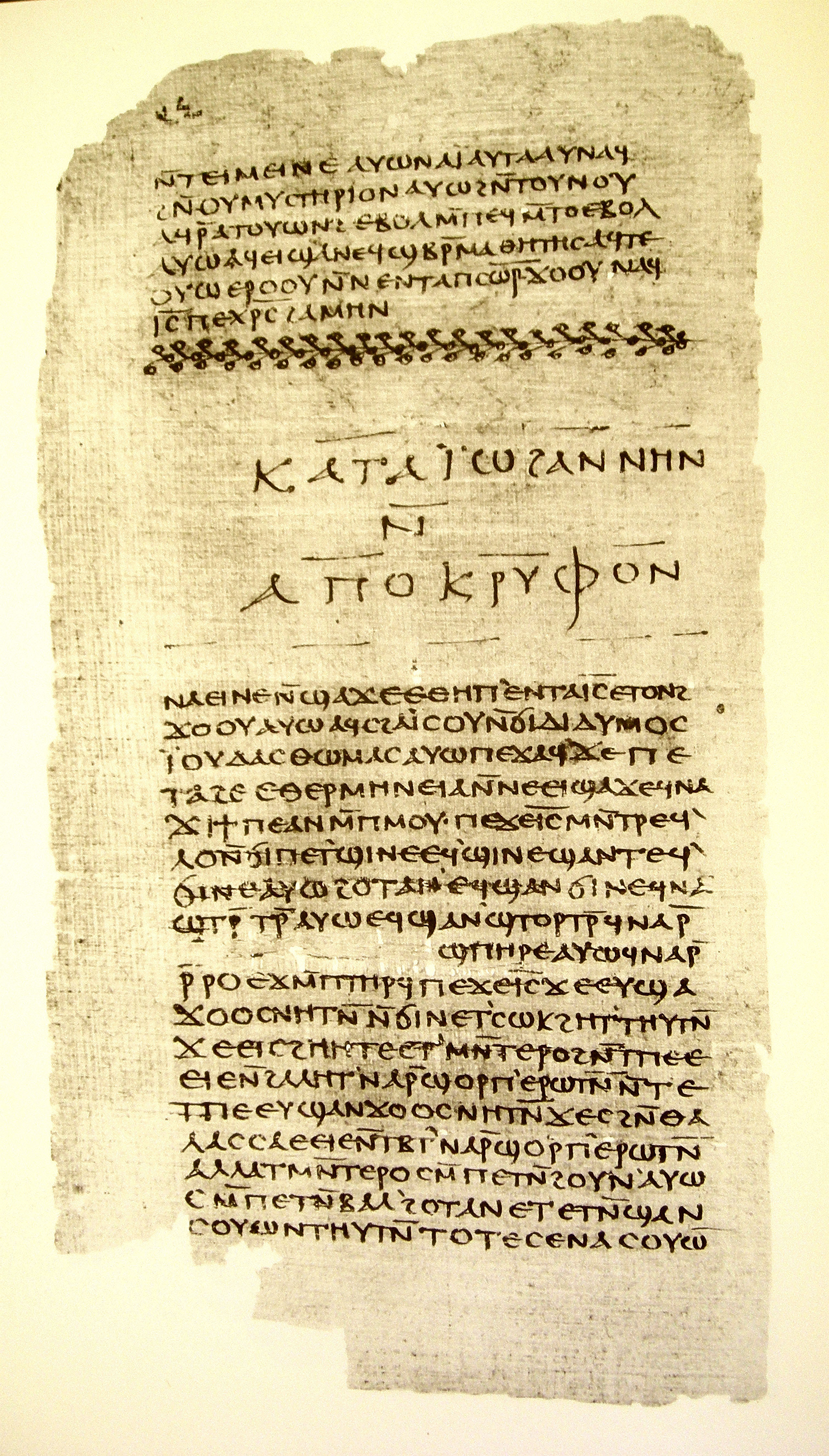

Beginning of the Gospel of Thomas, found at Nag Hammadi in 1945

These sayings are, by name/general summary: Kingdom and Children, The Mustard Seed, Blessed the Poor, When and Where, Two as One, The Lord’s Prayer, Greater Than John, The Planted Weeds, The Pearl, The Leaven, and The Treasure.

These sayings can be divided into four categories regarding their eschatological implications: ambiguous, neutral, apocalyptic, and anti-apocalyptic (favoring a “realized eschatology”), plus a special fifth category that deserves special attention. By my judgment:

Kingdom and Children and Blessed the Poor are neutral;

Only The Treasure is ambiguous (this is one of Jesus’s most confusing parables, and the disparate versions in Matthew and Thomas don’t help);

Lord’s Prayer and The Planted Weeds are unambiguously apocalyptic;

Mustard Seed, Two as One, Greater than John, The Pearl, and The Leaven are anti-apocalyptic;

And finally When and Where is apocalyptic in some forms, anti-apocalyptic in others. This requires careful explanation and hinges on the term “Son of Man.”

Before we get to that, let us deal with the other two explicitly apocalyptic sayings, Lord’s Prayer and The Planted Weeds.

The Lord’s Prayer comes to us in three versions; one in Matthew, one in Luke, and a third in the Didache that is extremely similar to Matthew.

If we accept the two-source answer to the Synoptic Problem, which I along with most scholars generally do, it seems clear that Luke’s shorter version of the prayer, which lacks any apocalyptic connotations whatsoever, is earliest. Generally, shorter forms of sayings are earlier; writers are much more likely to add than subtract. Matthew, as I’ve noted, is by far the most apocalyptic of the Synoptic gospels, and it makes sense for him to have added a plea for the Kingdom to hurry up when he was adapting from Q. The inverse theory, that Luke used Matthew as a source, claims that Luke took the second petition away because Luke had an anti-apocalyptic bias. This may sound convincing unless you know that A.) Matthew had already intensified the apocalypticism of Mark, and B.) Luke preserves other apocalyptic sayings intact.

(Quick aside: this would suggest that the Didache is dependent on Matthew, or vice-versa, a minority but very plausible opinion. I’m fine with that).

So I take the apocalyptic reference in the Lord’s Prayer as a probable interpolation, and certainly as not going back to the historical Jesus. The Planted Weeds, found in Thomas 57 and Matthew 13:24-30, speaks of weeds being separated from the good wheat and burned at the time of harvest. It is an interesting addition to Thomas, which is generally anti-apocalyptic. In any case, Matthew shows his hand a few passages later, when he literally has Jesus interpret this parable to his disciples: “The one who sows is the Son of Man; the field is the world, and the good seed are the children of the kingdom; the weeds are the children of the evil one, and the enemy who sowed them is the devil; the harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are angels” (Matthew 13:37-39).

This should remind you of Augustine’s and Origen’s absolutely absurd allegorical interpretation of the Good Samaritan, in which literally every element of that story is a stand-in for something else (the inn, for example, is the Church). This way of reading parables has been criticized by everyone from John Calvin to CH Dodd (who, by the way, coined the term “realized eschatology”). The idea that Jesus himself would interpret his own parable (which defeats the purpose of a parable) in such a heavy-handed way is, quite frankly, absurd, and so Matthew’s usage if not the saying itself must fall under heavy suspicion.