The book of Deuteronomy occupies a strange place in the Old Testament canon. It is considered the final part of the Torah or Pentateuch, but in many ways it actually seems to work better as the prelude to the historical books that follow (Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1-2 Samuel, and 1-2 Kings).

It’s been 40 years and God’s people are finally ready to take possession of the promised land. They’re on the border, getting ready for the invasion. Decades of trials and tribulations have led to this moment. We are on the cusp of the climax of this story. Every piece is in place…

But don’t think for a second that we don’t have time for an entire book’s worth of laws before we get to the fun part!

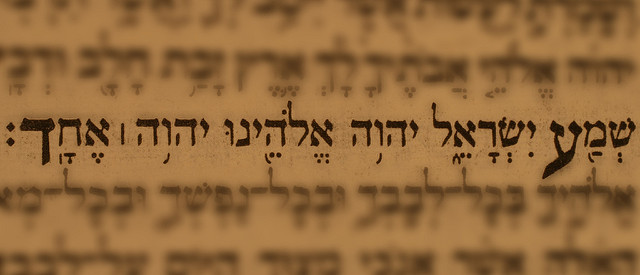

Deuteronomy begins with a lengthy recap of the journey of the Israelites since the Exodus (which reminded me of one of those “previously on…” teasers you see at the beginnings of episodes of a television show), and then most of the rest of the book is taken up by more laws and commandments by Moses, many of them darker and more violent than what we’ve seen thus far (which is saying a lot). If you can get through that, your reward is a lovely bit of poetry at the end, and then Moses dies.

Deuteronomy lays the foundation for all manner of horrible theologies and exegeses conceived in the millennia since it was written. It all comes down to chapter twenty-eight, a treatise modeled on the suzerain-vassal treaties common in the ancient Near East, especially in Assyria. Essentially, they were treaties between a conqueror and his conquered, and detailed the mutual obligations between both parties, focusing on blessings provided to the vassal for fidelity, and curses for disloyalty. Sound familiar?

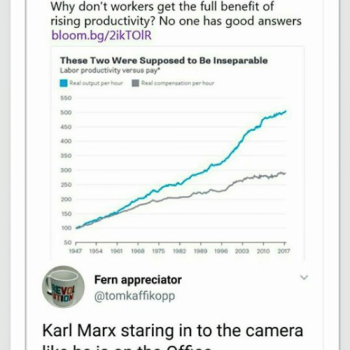

This is by no means a new or unique observation; I knew about it going in. Still, actually reading the “Blessings for Obedience” and “Warnings against Disobedience” sections in chapter 28, and seeing with my own eyes that the “warnings” section was more than three times as long as the “blessings” section really drove the point home.

On its own, this section of course refers specifically to the first generation of Jews in Israel, who had an insane history of turning their backs on Yahweh basically for shits and giggles, but divorced from this immediate context (as all theology is by nature), Deuteronomy creates a God that favors the powerful and privileged, as well as divine justification for an imperfect status quo.

Think of it this way: the covenant is meant to refer from present to future. If you are faithful, if you keep these commandments, you will be blessed; if you are treacherous, you will be punished. It is a very minor jump from this to a present-past movement, where, as John Dominic Crossan puts it in my favorite book of all time, “You are blessed, therefore you obeyed; you are cursed, therefore you disobeyed” (p. 94).

See, the wealthy and powerful are such because they are good and have obeyed the will of the Lord. The poor and dispossessed are such because they are wicked and unfaithful. This attitude deactivates all concern and compassion for the needy, for the orphan and the widow and the stranger. After all, they deserve it, don’t they?

This toxic idea in some form or another is at the root of evils ranging from divine right to the Prosperity Gospel. It is opposed even by other authors of the Hebrew Bible, most famously by Job (see Robert Frost’s play “A Masque of Reason” where God himself admits that the purpose of Job’s suffering was “to stultify the Deuteronomist”).

The sad part is that there is more to Deuteronomy than this awful idea. There is also the promise of renewal of the covenant when Israel inevitably fails; there are the beautiful words of the Song of Moses; there are the laws meant to protect the orphan and the widow and the resident alien. Unfortunately, in my mind and the minds of many others, the first thing that comes to mind when we hear the name of this book is sanctions and punishments.

Next week, Joshua takes the Israelites into the promised land.