An emphasis on “family values” has been a hallmark of conservative Christian ideology since the 1970’s, when pastors and think tanks began speaking out against the social liberalism of the 1960’s, typified by the Civil Rights Movement, hippie culture and free love, and second wave feminism.

An examination of these values, their origin, and their scriptural basis, however, reveals that they are quite antithetical to the message of Jesus and thereby profoundly anti-Christian.

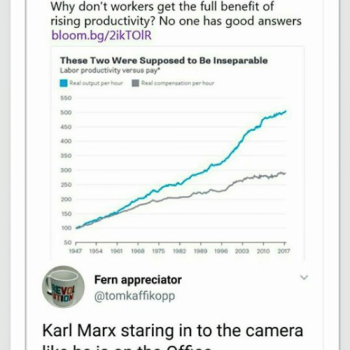

The 1970’s saw an economic recession throughout the western world, which marked the end of post-WW2 economic growth. It must have been a frightening time for many Americans who had thought that economic prosperity was permanent, and as conservatives are wont to do, they reacted by seeing the crisis as a result of moral failings of individuals (think “God punished New Orleans with Katrina because of the gays”).

Never mind that the economic collapse had evident systemic and conditional causes – the 1973 oil embargo and the heavily-industrializing Soviet bloc among them – economic uncertainty was a sign that the American people were turning away from God.

Reactionary Christians found all manner of progressive social movements to blame for the trouble the country faced: abortion had been declared a right by the Supreme Court, the Civil Rights movement for African Americans had inspired marginalized groups such as the LGBT community to start movements of their own, and more women were demanding the right to make choices about family planning and entering the workforce.

Implicit in all of this is a challenge to the nuclear family, the backbone of American society since the end of World War 2. What the nuclear family stands for, ultimately, is a paternalistic hierarchy also found in the New Testament (especially the letters of pseudo-Paul). The husband as householder and head-of-family over the wife as homemaker and bearer-of-children, with the children at the bottom of the pyramid, mimicked Christ-as-bridegroom and church-as-bride, with the laity as the children at the bottom.

Although the identity of conservative Christianity has evolved somewhat in recent years (“religious liberty” is fast approaching the level of exemplification that “family values” has held), the ideas that make up Christian family values are still at the core of conservative Christianity.

The standard-bearer of family values Christianity is the organization Focus on the Family, whose mission statement reads:

To cooperate with the Holy Spirit in sharing the Gospel of Jesus Christ with as many people as possible by nurturing and defending the God-ordained institution of the family and promoting biblical truths worldwide.

The “God-ordained institution of the family.” That is the key phrase.

But precisely when, where, and how did God ordain this institution? Since Christians, by definition, must base their conception of God in the figure of Christ, it is instructive here to explore what the historical Jesus believed and taught about the institution of the family.

For clarification, I want to state my long-held belief that there is no difference between the “Jesus of history” and the “Christ of faith.” They are the same person, and if the Jesus of history is not your Christ of faith, you are doing Christianity wrong.

While the “traditional family” of Jesus’s time looked different than the nuclear family of conservative America, the role it played in society was similar. In the Roman-Jewish-Mediterranean world of 1st-century Palestine, the extended family was the smallest unit of society, just as conservative Christianity views the nuclear family (as opposed to the individual) as the building block of American society.

The head of the Mediterranean family unit was the paterfamilias, usually the elder male of the family and often the grandfather. His male children and their male children worked to support the family, while daughters were married off to other families (other daughters, of course, married into their family). Extended families often lived together, working their ancestral land and providing for the family’s name over generations.

That was the ideal situation. Jesus’s experience, however was different. His class upbringing must be considered before any examination of his views on the family, because as Friedrich Engels put it in the preface to The Origins of the Family, Private Property, and the State:

“…the determining factor in history is, in the final instance, the production and reproduction of the immediate essentials of life…On the one side, the production of the means of existence, of articles of food and clothing, dwellings, and of the tools necessary for that production; on the other side, the production of human beings themselves, the propagation of the species. The social organization under which the people of a particular historical epoch and a particular country live is determined by both kinds of production: by the stage of development of labor on the one hand and of the family on the other.”

Both orders of production are crucial aspects of the life and ministry of Jesus.

Jesus’s father Joseph died at some point. Jesus was the oldest of at least seven children, but because of the rate at which families procreated back then, we need not assume Joseph died when Jesus was already an adult. Jesus might have become the nominal head of his family at a young age; unfortunately, there is no way to know for sure.

Either way, Jesus was a tekton, a manual laborer, a class of workers barely a step above slaves. His family had no ancestral land to farm; essentially, they were what Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels would eventually call proletarians (a word aped from the Romans), exploited wage earners with no access to any means of production.

These experiences doubtlessly had a profound impact on the young Jesus, who, like many Jews of that time and place, turned to a sort of religio-nationalism to make sense of the imperialist experience. First under John the Baptist, and then as the founder of his own movement, Jesus would challenge the cultural and political institutions of Mediterranean society in a quixotic attempt to bring God back to Israel.

One such institution, of course, was the “traditional family.” Jesus’s experience of class and race domination caused him to envision a different type of society, marked by the reversal of fortunes and, eventually, a society without hierarchy. This was the imminent Kingdom of God.