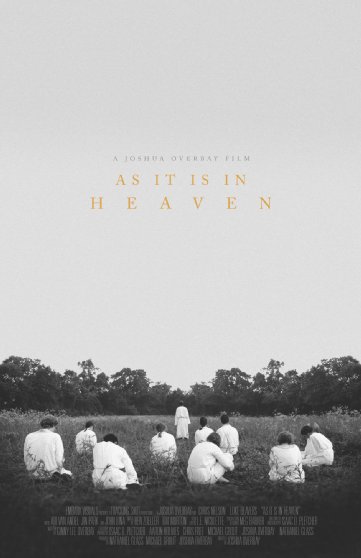

You can learn everything about Joshua Overbay’s naturalistic, haunting film As It Is in Heaven from the opening and closing scenes.

You can learn everything about Joshua Overbay’s naturalistic, haunting film As It Is in Heaven from the opening and closing scenes.

I was surprised at how it began. I was told this was a film about a doomsday cult, but the first scene is idyllic, peaceful, beautiful. A simple young woman readies herself for the day. She pins her hair up, dresses in white, and walks peacefully through rural wildflowers and trees, heading down to the bank of a river. As she goes, she sings a hymn quietly to herself. At the bank of the river, she meets others dressed in white. A young man is being baptized that day. His name is David (Chris Nelson). The religious sect may be distanced from the world, they may be awaiting the second coming of Christ on a specific date, they may believe themselves alone to be the loved and elect of God, but there doesn’t really seem to be many signs of cultishness otherwise. There is connection to creation, despite their belief in an impending end. There is fervent, sincere worship. There are loving relationships amongst the members of the group. Nobody seems bent on harming anybody else (although if they truly believe Jesus is returning to judge the world, I wonder why they aren’t out preaching this message to others). There’s no aggressive behavior to anyone; they just fervently want Jesus to appear.

We are drawn to David. He seems compassionate and simple. He gently welcomes a new member of the sect, despite her obvious nervousness. He seems kind and sincere and well-intentioned. We do not think of him as a cult leader. Nor do we really think of the spiritual father (Edward, played by John Lina) of this group as a stereotypical cult leader. He too is warm and kind, like an old-fashioned pastor.

But then Edward dies rather suddenly and unexpectedly. The group must adjust their thinking. They had thought that he would be the one to usher them into Christ’s second coming. On his deathbed, Edward tells David that he–not Edward’s son, Eamon (Luke Beavers)–is to be the next prophet. He tells David that he, Edward, did not do enough to purify the sect and prepare it for the second coming of Jesus. He may or may not be delirious when he says this. Or he may be trying to find a way to deal with his own religious disappointment.

At any rate, David takes on the mantle of leadership with a relentless, perfectionistic, obsessive drive that Edward never seems to have had. David seems committed to a neo-Platonic division of spirit and body. Flesh is evil; spirit is good. He tells the religious sect that they must fast for the remaining 30 days until the date the prophet has predicted the second coming. They must go through the purification of suffering.

We see a subtle shift. A people who may have been called out from the wider society become more distanced still–a people distanced even from their very physicality. The religious sect moves from a gentle, peaceful, and even joyous sect to increased fanaticism. As often is the case, this is motivated by a faith crisis. When God doesn’t make sense, all too easily people of faith interpret the faith crisis as a demand for greater devotion by a harsh, difficult-to-please God. Such a conclusion owes more to paganism than to Christianity. It makes me think of the prophets of Baal in the Old Testament.

Then they called on the name of Baal from morning till noon. “Baal, answer us!” they shouted. But there was no response; no one answered. And they danced around the altar they had made.

27 At noon Elijah began to taunt them. “Shout louder!” he said. “Surely he is a god! Perhaps he is deep in thought, or busy, or traveling. Maybe he is sleeping and must be awakened.” 28 So they shouted louder and slashed themselves with swords and spears, as was their custom, until their blood flowed. 29 Midday passed, and they continued their frantic prophesying until the time for the evening sacrifice. But there was no response, no one answered, no one paid attention.–I Kings 1:26b-29 NIV

The idea that we have to whip ourselves into a frenzy to get God to notice us is a pagan and not a Judeo-Christian idea. But crises of faith can cause us to do strange things to resolve the tension between the hidden God and the revealed God, between that which is seen and that which is yet to come. The shift is subtle. Instead of awaiting Jesus’s return with joy, with integration with creation, with the warmth of community, with a sense of God’s love, there comes a shift to a harsh focus on perfection and on shedding the mortal shell that is viewed as holding the human being back from true spiritual purity.

And so it is with the sect in this film. They are deeply devoted to their faith, they fear that it’s their fault that the first prophet has died, and they are determined to prove their love for Jesus by laying everything else aside for Him. They enter into the 30-day fast, grimly packing away the last of their food and giving it to a shelter.

There’s one problem though. And it’s a really disturbing one.