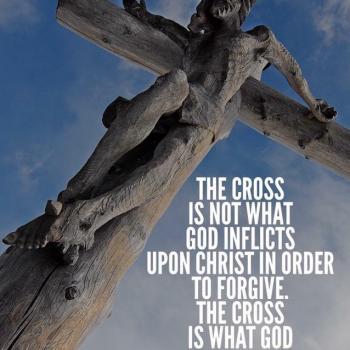

I was going to write the words below when sharing a link to Bob Cornwall’s post about forgiveness as a theological construct. But as I developed my thoughts, I decided it might be better as a post on my own blog. Here is what I was (and of course still am) inclined to share:

The meaning of the cross is not that Jesus somehow makes it possible for God to forgive us, or persuades God to do so. The meaning of the cross is that the one being mangled and killed by unjust social structures doesn’t merely forgive, but does so in a way that overcomes those doing it to him both personally (not simply playing the role of passive victim) and socially (beginning a process that undermines and transforms them).

Whether or not one believes in an afterlife, and if so in what form, turns out not to matter to this particular subject as much as one might expect. There are individuals who conquered their would-be conquerors in and beyond death even if they do not persist consciously as a soul or rise again in a new body. This is not to say that one should not believe such things – just that it isn’t essential to viewing Jesus as victorious in and beyond death. This is important, however, because of a tendency many have to focus on rewards in an afterlife as what really matters, as an end in themselves rather than a solution to a terrestrial problem of injustice. Often, in doing so, the end result is to prop up and maintain injustice rather than combat it – whether in life or in death. Jesus’ death is not a victory because this life doesn’t matter. It is a victory because he chooses to love his enemies to the end of his life, and then beyond it has an impact on his followers and ultimately the world that transforms it in powerful ways.

On that topic, see also Emma Higgs’ post about whether belief in an afterlife is good for humanity, and Jonathan Jong’s article about religion as a means of managing the terror of death, in which he writes:

On my more cynical days, I interpret the Church’s reminding us that we must die as a ploy, a means to sell to the faithful their opiates. But this runs contrary to my own experience of Christianity. The Bible is much less interested in what happens to us after we die than in what Christ’s defeat of death means for us here and now. It is clear, for example, that baptism — our rite of initiation — is meant to be a kind of death: it is a symbolic drowning. The point is not that we will one day die but that we are already dead, men and women walking unencumbered by the trappings of life in an often cruel and vicious world, red in self-protective self-destruction. The famous ethical injunctions — to turn the other cheek, to sell our possessions to give to the poor, to love our enemies — flow from this basic premise that we are no longer our own but have given ourselves up for the sake of a world in desperate need of love.

Of related interest, Keith Giles wrote (having been accused of “heresy” for not holding “the right view” of Jesus’ death and what it accomplished:

Everyone is someone’s heretic. At least, that’s my opinion these days. Whenever someone calls you a false teacher or a heretic, what they really mean to say is: “Your theology isn’t the same as mine. I can’t be wrong about anything, therefore you must be a heretic.”

What these people don’t realize is that, to someone else, they are the heretic.