The key question of Easter is not one that historians can answer. Did God vindicate Jesus beyond death? But that doesn’t mean historical research is irrelevant to everything to do with Easter. As one example, Phillip Jenkins blogged about the ending of the Gospel of Mark, drawing much the same conclusion as I do about connections between a lost ending, the Gospel of Peter, and chapter 21 of the Gospel of John. See my book The Burial of Jesus for my views on resurrection and the limits of history.

Recognizing that history cannot answer all questions doesn’t require adopting the view that historians cannot tell us anything, with varying degrees of certainty appropriate to the evidence available.

The question of whether there was ever a historical Jesus, for instance, is most certainly susceptible to an answer by historians, who have been absolutely clear about what they conclude and why. Yet somehow atheist “skeptics” manage to reject the perspective of secular historians in the same way they reject theological claims. Once one has gotten into the habit of trusting one’s own insight and debunking skills in response to church “experts,” those skills prove remarkably easy to transfer to other realms, leading inevitably to the embrace of one or more additional conspiracy theories.

Here is what I wrote in seeking to reach a self-proclaimed “fence-sitter” about the historicity of Jesus, in response to a request for a brief presentation of the case:

I am happy to try to offer what you are looking for, and would like to at least begin conversationally, if that is OK with you, to address the question of which figures are appropriate comparisons.

First, can we agree that figure such as Roman empersors and Alexander the Great are inherently likely to leave behind more evidence, and of a different sort, than an itinerant rabbi, exorcist, and/or messianic claimant?

If so, would you agree that, even if we do not have the same sort of evidence for figures like Hillel or Akiba (two famous Jewish rabbis of the period), though that will make their historicity less certain than the minters of coins and inscribers of monuments, that does not make it inherently unlikely that they existed in and of itself? In other words, that the evidence will inevitably vary and our certainty should span a spectrum, with room for high degrees of certainty towards the ends but also varying shared throughout im between?

Could we then perhaps also agree that figures like King Arthur and Ned Ludd (and Robin Hood and John Frum and Prester John and many others) are often simply of uncertain hiistorical basis? No historian would deny that the Arthurian legends are legends, fictions plain and simple. But do we know with a high degree of confidence that they are not fictions that used a name that people recalled as that if an actual person? In other words, that the question of whether all, most, some, or little of our information about a person is even attempting to be accurate and factual, never mind succeeding, may not tell us whether or not there is a historical figure faintly visible, or obscured in all but name, from a historian’s view?

You may be detecting a pattern in this. This is all about aiming at nuance that tends to get lost not just in discussions of mythicism, but any kind of apologetics. It may seem to score points in internet debates if someone gets someone else to admit that they are not completely certain about something. But uncertainty is par for the course in historical study, and tackling this seems a necessary step before proceeding further.

What if anything would you have said differently? I continued later, once we got past some of these preliminaries:

Do you just want to dive into one of the pieces of evidence? If so, we certainly can. But it obviously requires assuming familiarity with the relevant sources.

Paul, in his letter to the Galatians, mentions a James that he refers to as “the brother of the Lord.” He obviously doesn’t mean “the brother of God!” Paul’s most frequent use of “Lord” is in reference to Jesus. And he cannot simply mean “James the Christian,” because even if one were to adopt the view that, like “brothers,” “brothers of the Lord” could denote Christians in general, it still would not make sense in that context, since in both places (also in the Corinthian correspondence) where Paul mentions brothers of the Lord, it is in distinction from other Christians. Is there a more likely meaning, then, than that he meant the literal siblings of Jesus in these instances? And if there were individuals in the early Jesus movement (not yet even called “Christianity” at this stage) who were known as the brothers of Jesus, and this claim was accepted even by people like Paul who disagreed with them, is it not more probable than not that these were in fact siblings of Jesus? Is the alternative not to pose some kind of conspiracy of a family to concoct a fictitious sibling?

Even if one were inclined to do that, then we’d have the character of the claims made about this Jesus. The Davidic anointed one was the awaited king that it was hoped would restore his dynasty to the throne and usher in a golden age of one sort or another. Being crucified pretty much disqualified you from being the person in question. Is it probable that a group that was concocting a message about the long-awaited king, which they planned to proclaim to others in order to persuade them to believe, would also invent that this individual was executed and thus at least apparently a failure and a thoroughly implausible candidate for the role?

All of these pieces and others fit together, just as the evidence for evolution does. I’m sure you know, if you’ve ever debated with an antievolutionist of some sort, that although there are individual pieces of evidence that are extremely compelling, it is really the overall picture that emerged from the evidence considered in totality that makes the conclusion so solid. I will also add that I am in no sense making this comparison so as to suggest that conclusions about biological processes that we can observe today and which have left lots of evidence are comparable in probability to conclusions historians draw about ancient people. On the contrary! Indeed, it is that very point that I sometimes find lies at the core of some people’s adherence to mythicism. They simply don’t realize that, whether we’re dealing with Socrates or Jesus, our evidence is texts, and in both cases texts that contain stories that we judge largely fictional. They can still provide a reason for judging these figures’ historicity to be more probable than not.

The conversation continued. Again, I have questions – in particular, how effective can an appeal of this sort be when someone is not well-informed not only about early Christian literature (except as Christian scripture) and not familiar with the broad historical and literary context in which Christianity appeared? The fact that the blog in question has lots of commenters who are mythicists and use popular internet “debate” tactics didn’t help.

Of related interest, see Bob Cargill on the problems of the census in Luke’s Gospel. We can tell (or indeed presume) infancy narratives are not historical without even investigating in detail. We find comparable infancy stories for historical figures throughout ancient literature. See too Chris Keith’s lecture about the Gospels and their historical accuracy or otherwise.

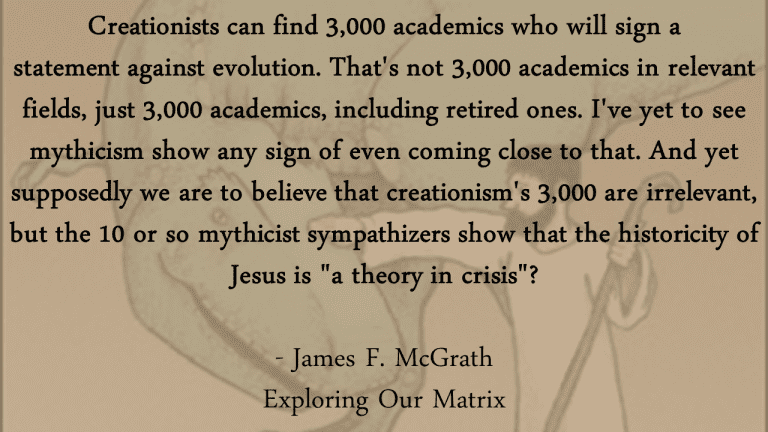

My analogy with the Dissent from Darwin list also came up in the discussion on that other blog about consensus. On that topic, see this meme I made some time ago:

And finally, for those who had the patience to read this far, a mythicist claimed to comment on “the state of scholarly mythicism.”