We denizens of the early 21st century might be justifiably feeling a bit disappointed. We used to naïvely anticipate a paradisiacal era of flying cars and hoverboards. But instead, the 2010s have turned out to mostly be a giant metaphorical freeway pile-up of everybody disagreeing with everybody else, about everything, all the time. Particularly on Internet comment boards. We suddenly seem to enjoy few commonly recognized truths, shared standards, or sense of collective purpose. Some blame postmodernism, which began in the universities in the 1970s but has since spread its doctrines of epistemic relativism into the broader culture. But postmodernism has two big opponents: scientism and religion. Understanding how these ideologies relate to each other might shed more light on our odd cultural moment than looking for blameworthy culprits could.

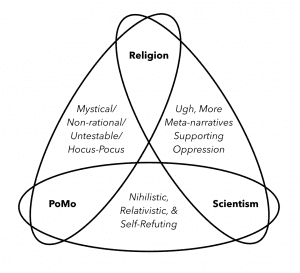

The three-way relationship between scientism, religion, and postmodernism is rich with irony. Each considers the other two to be its sworn enemy, yet both of its adversaries lump it into a common category with the other. That is, each position – scientism, religion, and postmodernism – sees the other two as merely superficially distinct expressions of the same basic, erroneous worldview. The result is a near-farcical comedy of errors, as highly visible spokespeople for each viewpoint make glaring category errors during their blustering attacks on their opponents.

For example, to advocates of scientism (or Science™), religion and postmodernism are basically the same bogeyman. They’re both defined by an irrational refusal to accept that verifiable, objective facts are the only proven source of knowledge. They trust inchoate feelings and impressions, hide their incoherent claims behind gobbledegook rhetoric, and stubbornly deny the practical supremacy of good, clear reason. It’s through the weed-choked channels of religion and postmodernism, then, that science denial, mysticism, and magical thinking flow like effluvia into the otherwise and forward-looking modern world.

But from the standpoint of postmodernists, traditional religious authority and Science™ are both illegitimate, hegemony-consolidating meta-narratives. They deny the multiplicity and plurality of the universe, stamping it instead with single one-size-fits-all explanatory and normative categories. Hence, traditional religious narratives and scientistic faith in progress are actually just interchangeable covers for the power interests of dominant groups. When powerful people claim that there’s a unitary, objective “Truth” out there, it doesn’t matter whether they’re wearing a frock or a lab coat: either way, they’re denying the validity of the many small-t “truths,” and using objective truth claims as normative cudgels to impose their worldviews on everyone else.

Finally, to religious believers (or at least Abrahamic religious believers), both Science™ and postmodernism are common symptoms of a single, underlying malaise: an egotism that discards the hard-won fruits of tradition, divine guidance, and timeless moral truths. Loss of these goods leads inexorably to relativism, specifically value relativism, which itself opens the way to nihilism – the arguments for which are self-refuting. Both Foucault fops and Dawkins devotees believe that human beings are fundamentally alone in an uncaring cosmos, and therefore free to do whatever they see fit. The result is a Nietzschean addiction to power and self-assertion.

For clarity, I decided to make a schematic to represent this three-way antagonism. But then I realized that there are really two ways of viewing the tensions between religion, scientism, and postmodernism. The first is to highlight the negative traits by which each position defines the dyad that comprises the other two. You can see this schematic in Figure 1. (Note that it’s not really a three-way Venn diagram; it’s a kind of Euler diagram instead. That’s because the intersection of the three sets is, as far as I can tell, empty.)

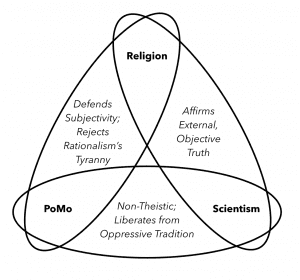

But you could also identify the positive values that each view shares with the others, producing a schematic that highlights the three potential binary alliances. This positive schematic is shown in Figure 2.

We’ve already discussed the mutual and conflicting antagonisms that are shown in Figure 1. So let’s turn our attention to what I think is more interesting: what each position shares with its seeming opponents.

The Irrational Friendship between Postmodernism and Religion

As Figure 2 shows, both religion and postmodernism see themselves as defending subjectivity against the rationalizing and objectifying pretensions of modern Science™ and its dreams of technological dominance. They resist any explanatory encroachments into the irreducibly personal domain of particular, interior existence. Their particularism defends the validity of a unique point of view in an otherwise vast and center-less cosmos.

This defense of particularism, then, produces an interesting irony: although critics accuse postmodernism of undermining the possibility of an objective point of view, postmodern philosophies paradoxically make it possible for actual, flesh-and-blood individuals to live in the center of the universe again. What do I mean? By denying the “view from nowhere,” postmodernism reminds us that we’re each stuck having a particular viewpoint: the one that happens to look out from our own two eyes. If you experience the world phenomenologically this way, the inescapable impression is that you live in the center of things. Massively de-centering epistemically and culturally, postmodernism cheekily re-centers the subject – putting it in good company with the millennia-old teachings of religious traditions.

Postmodernism and Science™: A Nontraditional Alliance

Postmodernism and Science™, meanwhile, are both deeply skeptical of traditional authority and its abuses – not to mention generally antagonistic to normative supernatural beliefs. Postmodernists may see the advocates of scientism as mere peddlers of yet another hegemonic meta-narrative. But in fact, Daniel Dennett and Jacques Derrida are equally eager to throw off the shackles of oppressive cultural traditions, or anything that smacks of arbitrary power. The Enlightenment is not so alien to the postmodern mind as it might think.

In fact, you could make a case that postmodernism is, paradoxically, the apotheosis of scientism. It assumes that everything that is arbitrary is unreal. For example, advocates of Science™ are skeptical of the culturally particular claims of unique religious traditions because those claims can’t be recovered from mind-independent facts. That is, no amount of purely objective inquiry using empirical methods would likely ever produce a demonstrable proof that (for instance) Jesus Christ is the second person of the Trinity. Therefore, we are expected to take claims about Jesus on faith. Therefore, they are culturally arbitrary – not universal. Therefore, they are false.

Postmodernism takes this scientistic point of view to its extreme, applying it to all cultural products, beliefs, or institutions that depend on special authority rather than on mind-independent facts. Institutions or social facts such as the United States, NATO, or even medical diagnoses are seen to be dependent on culturally particular authorities, norms, and local hegemony over discourse. Therefore, they are not universal. Therefore, they are false (and often pernicious). This is why, for instance, calls for the abolition of national borders have spiked among left-leaning citizens of Western nations just as postmodern ideas have spread in earnest from academic contexts into the wider educated community. Postmodern ideas entail that entities that are mind-dependent – that is, things that depend on normative cultural authority, not on objective fact – are illegitimate. But this conclusion is merely the logical extension of the anti-authoritarianism that also animates Science™.

Religion and Science™: Let’s Be Objective

Finally, religion and Science™ may not be best friends, but one absolutely critical shared value sets them off against postmodernism. This value is firm belief in external, objective truth. Yes, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Sam Harris don’t agree on what that truth is. No, we shouldn’t expect them to compromise on this. If the Church of England decided that Sam Harris was right about what the universe really is, it’d have to close up shop. Religion largely teaches belief in a transcendent truth, Science™ in an immanent or material one. These are not the same.

But granted these intractable differences between religious believers and advocates of scientism, the fact that they both affirm that there is an objective truth is no small potatoes, particularly in an era when the concept of truth is taking a sound beating. Although some advocates of scientism may be guilty of a bit of arrogance, at the end of the day it’s difficult to agree with Protagoras that “man is the measure of all things” if you also think that the laws of nature are real, are discoverable, and will potentially kill you if you get them wrong. Dealing with problems that have definite answers enforces a kind of humility. Postmodernists don’t deal in questions that have single answers you can either get right or wrong. They deal in rhetoric. They deal in discourse. Both scientists and religious believers deny that truth boils down to rhetoric. They think there’s a there there, which you can either recognize or not. It won’t change the truth either way. Because the truth is the truth.

Frenemies Aren’t Black and White

The fact that each ideological position in our tripartite diagrams holds values in common with both of the others makes it hard – impossible, actually – to see our current debates about truth, reality, and authority as binary or black-and-white. Religious believers may disagree vehemently with advocates of Science™ about the meaning and purpose of life. But they both might be tempted (if they could stop fighting) to opportunistically join forces against the extreme voices of relativism in the postmodern era. Postmodernists might see Science™ advocates as purveyors of just another hegemonic meta-narrative, but they both might stand up together against the most oppressive or dangerous intrusions of tradition into spaces that call for exploration and individual autonomy. And religious believers are certainly galled by postmodernism’s moral relativism and the nihilism it threatens, but they share with it a profound mistrust of the reductive aspirations of scientism to objectify and explain everything. They feel the same powerful urge to stand up and cry out that some things cannot – and should not – be “explained.”

Of course, the three positive intersections are really just positive glosses on the negative traits that define the antagonisms in Figure 1. But by describing them in terms of positive values, we can see more clearly how an arena that most of us think of as boiling with pure enmity on all sides is actually criss-crossed with powerful alliances. This might not lead to better communication (especially on the internet). But it does give us a map of the values that are implicitly driving so many conflicts and changes in many spheres. These range from academia (including the cognitive and biological study of religion, which is perfectly poised to alienate all three positions in different ways) to journalism, politics, and tech. A map isn’t a vehicle. It won’t get you where you’re going. But it can show you where you are.

_____

I’ve been writing about this topic lately because my job as an evolutionary social scientist of religion puts me in the crosshairs of all three ideologies. The post-truth era is putting questions of relativism, epistemology, and faith front-and-center in our public discourse, so it seemed like it couldn’t hurt to explore the underlying tensions more thoroughly and carefully – both for my own sake and for that of the readers of this blog. Read previous posts on religion, science, and postmodernism:

What Is Postmodernism? And Why Does it Matter for Science?

Measuring the Evolution Gap between the Humanities and Sciences

Why Postmodernism and Science Can’t Stand Each Other

What Is Religion Studies? Or: No, Grandma, I am Not Going to Be a Pastor