Part 1 in a series on the mangling of Darwin’s Autobiography. Part 2 | Part 3

Charles Darwin wrote a great book. I loved it the first time I read it, then read it twice more. The more I read it, the more I liked it.

Not everyone feels the same about this book. Some were so disturbed by what he wrote that they cut whole passages out before it was even published. As a result, most people didn’t get to read the book in its complete and original form until 1958, when the excised passages were restored.

What? No no, not that Darwin book. I’m talking about his Autobiography.

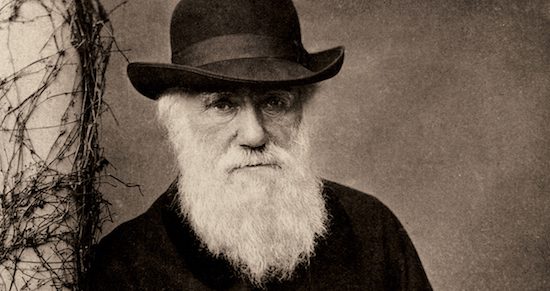

Darwin sat down to write his autobiography in May 1876, “as if I were a dead man in another world looking back at my own life. Nor have I found this difficult,” he added, “for life is nearly over with me.”

I’m guessing he knew this from the title page he had just written: Charles Darwin (1809-1882). Chills.

The idea to write a sketch of his life came from Julius Victor Carus, a zoologist in Leipzig who had translated the Origin into German and needed some bio from Darwin for an encyclopedia entry. Ten years later, Darwin decided to write “recollections of the development of my mind and character,” driven in part by realizing “that it would have interested me greatly to have read even so short and dull a sketch of the mind of my grandfather [Erasmus Darwin] written by himself, and what he thought and did and how he worked.”

He also said he thought the attempt at such a thing “would amuse me, and might possibly interest my children or their children.”

Ironically, one of his children would end up slicing up Charles’s recollections, and one of his children’s children would made it whole again.

The Autobiography first appeared publicly as part of Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, edited by his son Francis and published in 1887.

Poor Francis is our villain in this tale. But the more you learn about why Francis Darwin did what he did, the harder it is to fault him too thoroughly. Unlike some other 19th century bowdlerizers, Francis acted out of primary concern for the reputation of the author, his father, and the strongly expressed wishes of his mother Emma. Usually the author’s desires are plenty clear — he wrote the words he wanted included. But there was some disagreement about whether Charles ever intended to publish it, which complicates the sorting of intent.

It got nasty. In the five years between Darwin’s death and the publication of the Autobiography, the Darwin family tore itself up over what should appear and not appear in the book. At one point, one wing of the family considered suing the other.

So Francis did his best. Then 71 years later, with the principals in the original fight all safely dead, his niece Nora Barlow did better.

In its buggered form, Darwin comes across as an undiscerning dodderer. He likes everybody and everything just fine, especially those alive at the time of publication. (In an interesting switch, Francis allowed him to speak ill only of the dead.) And the wonderfully complicated ebb and flow of his opinions on religion is reduced to a hazy, misleading mumble in favor of the status quo.

Fortunately for me, it was Nora’s restored edition that reached me first, which is probably why I read it more than once. But I wasn’t fully aware of its tortuous history until much later.

I’ll start next time with the whitewashing of his commentaries on the people around him, then get to religion in Part 3.

All images in this series via Wikimedia

DALE McGOWAN is the author of Atheism for Dummies and Raising Freethinkers. He lives in Atlanta.